Det Udenrigspolitiske Nævn 2004-05 (1. samling)

Bilag 5

Offentligt

Human Rights Watch

October 2004 Vol., No. ()

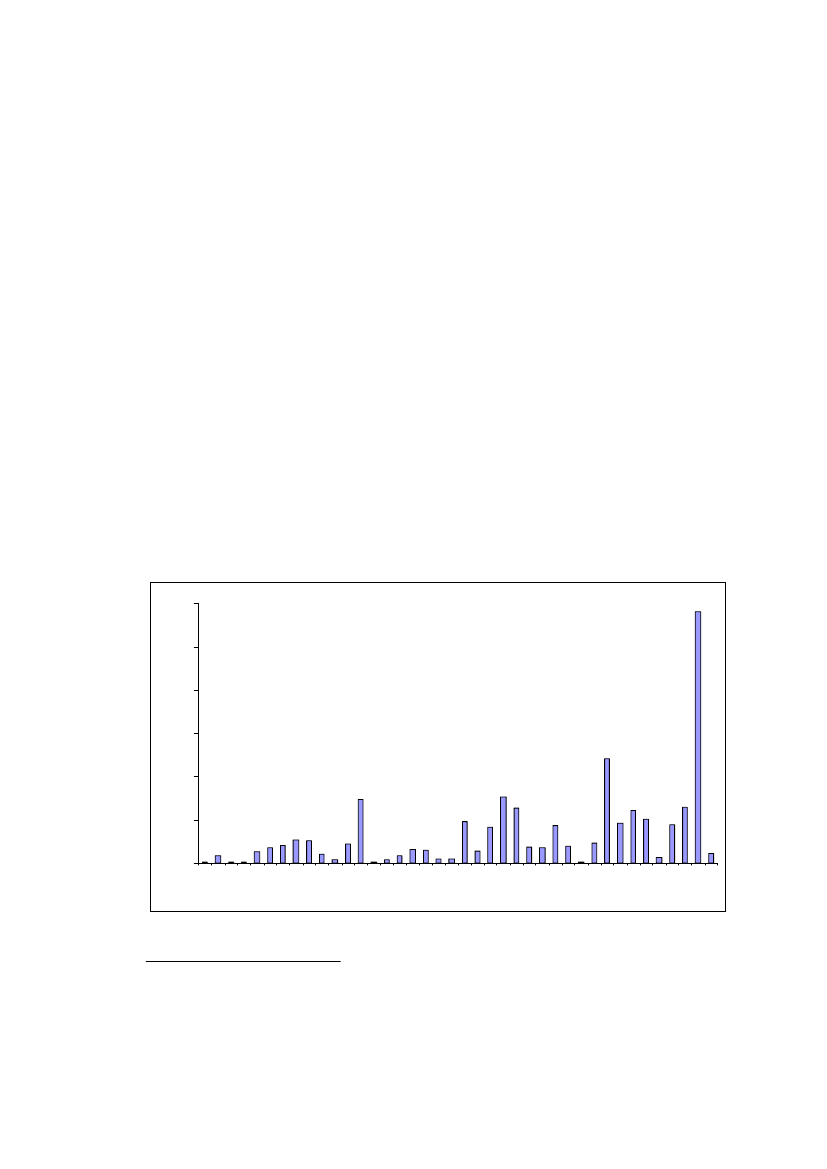

Razing Rafah:Mass Home Demolitions in the Gaza StripI. SUMMARY................................................................................................................................ 1A Pattern in the Rubble ........................................................................................................... 3Tunnels................................................................................................................................... 3Protecting the Border........................................................................................................... 5Rampage in Rafah: May 2004.................................................................................................. 8Doctrines of Destruction....................................................................................................... 11Nowhere to Turn.................................................................................................................... 14Methodology............................................................................................................................ 14II. RECOMMENDATIONS.................................................................................................... 15III. BACKGROUND ................................................................................................................ 19Map 1: Gaza Overview (Map 1: Gaza Overview) [place opposite page to the text] ........ 21The Uprising in Gaza: From Closure to “Disengagement”............................................. 22Photo: Tent.JPG.......................................................................................................................... 24Map 2: Rafah Features (Map 2: Rafah Features) [place opposite to the text].................... 26Rafah ......................................................................................................................................... 26Mass Demolition: Security Rationales, Demographic Subtexts....................................... 28Photo: Rubble.JPG ..................................................................................................................... 29IV. THE SECURITY SITUATION IN RAFAH................................................................. 32Photo: Outpost.JPG ................................................................................................................... 32The IDF and Palestinian Armed Groups............................................................................ 33Fighting on the Border........................................................................................................... 35Smuggling Tunnels in Rafah ................................................................................................. 38An Overview ....................................................................................................................... 39Tunnels vs. Shafts............................................................................................................... 42Destruction Around Inoperative Tunnels ...................................................................... 44Alternatives to House Destruction .................................................................................. 47V. THE RAFAH BUFFER ZONE SINCE 2000................................................................. 51The Expanding Buffer Zone................................................................................................. 52Photo: Wall.JPG .......................................................................................................................... 53GRAPH 1: House Demolitions in Rafah by Month, October 2000-June 2004 ............... 53Map 3: Buffer Zone Expansion (Map 7: Block O Patrol Corridor/Buffer ZoneExpansion) [place opposite page to the text].......................................................................... 54New Realities: Widening the Buffer Zone .......................................................................... 54Map 4 : Existing and Proposed Buffer Zones (Map 12: Buffer Zones) [place oppositepage to the text]........................................................................................................................... 58Impact of Destruction............................................................................................................ 59

1

HUMAN RIGHTS WATCH VOL. NO. ()

Photo: School.JPG (Can be dropped)...................................................................................... 59Photo: Qifaya. JPG (Can be dropped)..................................................................................... 60Photo: Jamal.JPG ........................................................................................................................ 60VI. A Violent Season: Destruction in Rafah, May 2004 ....................................................... 61Rampage in Rafah: An Overview ......................................................................................... 62Map 5 : IDF Operations in Rafah May 2004 (Map 3: Rafah Incursions) [place oppositepage to the text]........................................................................................................................... 62Rafah Incursions by Neighborhood, May 12-24................................................................ 70Block O & Qishta (evening May 12-morning May 15)................................................. 70Map 6 : Tel al-Sultan 2004 (Map 8: Tel al-Sultan) [place opposite page to text]............... 75Tel al-Sultan (May 18-May 24).......................................................................................... 75Photo: Sabir.JPG (Passport Size).............................................................................................. 76Photo: Sandbag.JPG ................................................................................................................... 77Photo: Sultan.JPG....................................................................................................................... 78Map 7: Brazil Features (Map 11: Brazil Before and After) [place opposite to the text]... 83Brazil and Salam (evening May 19-morning May 24) ................................................... 83Photo: Hamaad.JPG (Can be dropped)................................................................................... 87Tactics of Destruction............................................................................................................ 90Home Demolitions to Enhance Mobility ....................................................................... 91Map 8: Brazil Destruction During Operation Rainbow (Map 10: Brazil Quarter,Rainbow) [place opposite to the text] ...................................................................................... 91Infrastructure Destruction ................................................................................................ 91Photo: Ripper.JPG ...................................................................................................................... 92Photo: Water.JPG ....................................................................................................................... 92Map 9: Razing of Agriculture (Map 9: Tel al-Sultan—Agriculture) [place opposite to thetext]................................................................................................................................................ 94Razing Agricultural Land................................................................................................... 94Photo: Agriculture.JPG .............................................................................................................. 94VII. ROLE OF THE INTERNATIONAL COMMUNITY ............................................. 94Paying for the Mess ................................................................................................................ 96VIII. PROPERTY DESTRUCTION UNDER INTERNATIONAL AND ISRAELILAW............................................................................................................................................100International Humanitarian Law ........................................................................................100Responsibilities of an Occupier: Military Operations vs. Security Measures ..........101Destruction of Property in Occupation: Military Operations and Absolute Necessity.............................................................................................................................................103Control of Property in Occupation: Security Measures and Rights..........................107Human Rights Law and Occupied Territories .................................................................108Forced Evictions and the Right to Adequate Housing...............................................109Right to Effective Remedies ...........................................................................................111

HUMAN RIGHTS WATCH VOL., NO. ()

2

Israeli Jurisprudence and Law.............................................................................................112Exceptions Over the Rule: Israeli Courts and Destruction of Property..................112Reparations ........................................................................................................................114IX. Appendix: Statements by International Community Condemning Destruction inRafah ...........................................................................................................................................116ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ..................................................................................................118

3

HUMAN RIGHTS WATCH VOL., NO. ()

Human Rights Watch

October 2004 Vol., No. ()

I. SUMMARYThese houses should have been demolished and evacuated a long time ago… Three hundred meters of the Strip along the two sides of the bordermust be evacuated … Three hundred meters, no matter how many houses,period.Major-General Yom-Tov Samiya,former head of IDF Southern Command1I built homes for Israelis for 13 years. I never thought the day would comewhen they’d destroy my house. … They destroyed the future. How can Istart all over now?Isbah al-Tayour, Rafah resident,former construction worker in Israel2Over the past four years, the Israeli military has demolished over 2,500 Palestinian houses inthe occupied Gaza Strip.3Nearly two-thirds of these homes were in Rafah, a denselypopulated refugee camp and city at the southern end of the Gaza Strip on the border withEgypt. Sixteen thousand people – more than ten percent of Rafah’s population – have losttheir homes, most of them refugees, many of whom were dispossessed for a second or thirdtime.4As satellite images in this report show, most of the destruction in Rafah occurred along theIsraeli-controlled border between the Gaza Strip and Egypt. During regular nighttime raidsand with little or no warning, Israeli forces used armored Caterpillar D9 bulldozers to razeblocks of homes at the edge of the camp, incrementally expanding a “buffer zone” that iscurrently up to three hundred meters wide. The pattern of destruction strongly suggests thatIsraeli forces demolished homes wholesale, regardless of whether they posed a specificthreat, in violation of international law. In most of the cases Human Rights Watch foundthe destruction was carried out in the absence of military necessity.

1

Voice of Israel Radio, January 16, 2002, cited in B’tselem,Policy of Destruction: House Demolitions andDestruction of Agricultural Land in the Gaza Strip,February 2002.Tsadok Yehezkeli, “Regards from Hell,”Yediot Ahronoth,June 11, 2004 (Hebrew).

23

Unless otherwise stated, statistics for homes demolished and persons rendered homeless were provided bythe United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East (UNRWA) based mostlyon assessments by its social workers. UNRWA classifies damage in three categories: total destruction, partialdestruction (rendered uninhabitable, in need of reconstruction), and damage (habitable, in need of repair).References to homes “demolished” or “destroyed” in this report refer to all those rendered uninhabitable, i.e. thefirst two categories, unless otherwise stated. UNRWA statistics also include data on the demolition of non-refugee homes.UNRWA’s operational definition of “refugee” includes descendents of those who fled or were expelled fromwhat became Israel (“Who is a Palestine refugee?” UNRWA website, available athttp://www.un.org/unrwa/refugees/whois.html,accessed September 24, 2004).

4

1

HUMAN RIGHTS WATCH VOL. NO. ()

In May 2004, the Israeli government approved a plan to further expand the buffer zone, andit is currently deliberating the details of its execution. The Israeli military has recommendeddemolishing all homes within three hundred meters of its positions, or about four hundredmeters from the border. Such destruction would leave thousands more Palestinianshomeless in one of the most densely populated places on earth. Perhaps in recognition ofthe plan’s legal deficiencies, the Israel Defense Force (IDF) is not waiting for thegovernment to approve the plan. Ongoing incursions continue to eat away at Rafah’s edge,gradually attaining the desired goal.This report documents these and other illegal demolitions. Based on extensive research inRafah, Israel, and Egypt, it places many of the IDF’s justifications for the destruction inserious doubt, including smugglers’ tunnels and threats to its forces on the border. Thepattern of destruction, it concludes, is consistent with the goal of having a wide and emptyborder area to facilitate long-term control over the Gaza Strip. Such a goal would entail thewholesale destruction of neighborhoods, regardless of whether the homes in them pose aspecific threat to the IDF, and would greatly exceed the IDF’s security needs. It is based onthe assumption that every Palestinian is a potential suicide bomber and every home apotential base for attack. Such a mindset is incompatible with two of the most fundamentalprinciples of international humanitarian law (IHL): the duty to distinguish combatants fromcivilians and the responsibility of an Occupying Power to protect the civilian populationunder its control.This report also documents with witness testimony, satellite images, and photographs, theextensive destruction from IDF incursions deep inside Rafah this past May. In total, the IDFdestroyed 298 houses, far more than in any month since the beginning of the Palestinianuprising four years ago. The extent and intensity of this destruction was not required bymilitary necessity and appears intended as retaliation for the killing of five Israeli soldiers inRafah on May 12, as well as a show of strength.Israeli Prime Minister Ariel Sharon’s plan to “disengage” from the Gaza Strip holds littlehope of relief to the residents of Rafah. Under the plan, the IDF will maintain itsfortifications and patrols on the Rafah border indefinitely. The plan explicitly envisions thepossibility of further demolitions to widen the buffer zone on the basis of vague “securityconsiderations” that, as this report demonstrates, should not require a buffer zone of thekind that currently exists, let alone further mass demolitions.This report recommends that the Israeli government cease its unlawful demolitions, allowdisplaced Palestinians to return, pay reparations to victims, pay to repair unlawful damage,and address the emergency needs of the displaced. The international community, whichfunded some of the infrastructure destroyed by the Israeli military and continues to pay foremergency relief, should press Israel to take these steps. In the meantime, if donors allocate

HUMAN RIGHTS WATCH VOL., NO. ()

2

funds to rehouse victims and repair unlawful destruction, they should demand compensationfrom Israel.

A Pattern in the RubbleThe Israeli military argues that house demolitions in Rafah are necessary primarily for tworeasons: to deal with smuggling tunnels from Egypt that run underneath the IDF-controlledborder and to protect IDF forces on the border from attack. Rafah is the “gateway toterror,” officials say – the entrance point for weapons used by Palestinian armed groupsagainst the Israeli military and civilians. Under international law, the IDF has the right toclose smuggling tunnels, to respond to attacks on its forces, and to take preventive measuresto avoid further attacks. But such measures are strictly regulated by the provisions ofinternational humanitarian law, which balance the interests of the Occupying Power againstthose of the civilian population.In the case of Rafah, it is difficult to reconcile the IDF’s stated rationales with thewidespread destruction that has taken place. On the contrary, the manner and pattern ofdestruction appears to be consistent with the plan to clear Palestinians from the border area,irrespective of specific threats.

TunnelsThe IDF argues that an extensive network of smuggling tunnels from Egypt requireincursions into Rafah that result in house demolitions. According to the IDF, a typicaltunnel-hunting operation requires Israeli forces to destroy a house covering a tunnel exit aswell as houses from which Palestinian gunmen fire at them during the operation.Based on interviews with the IDF, Rafah residents, the Palestinian National Authority(PNA), members of Palestinian armed groups, and independent experts on clandestinetunnels, Human Rights Watch concludes that the IDF has consistently exaggerated andmischaracterized the threat from smuggling tunnels to justify the demolition of homes.There is no dispute that tunnels exist to smuggle contraband, including small arms andexplosives used by Palestinian armed groups, into the Gaza Strip. But despite thetremendous burden that demolitions have imposed on the civilian population, the IDF hasfailed to explain why non-destructive means for detecting and neutralizing tunnels employedin places like the Mexico-United States border and the Korean demilitarized zone (DMZ)cannot be used along the Rafah border. Moreover, it has at times dealt with tunnels in apuzzlingly ineffective manner that is inconsistent with the supposed gravity of thislongstanding threat. The report makes three main points:Shafts vs. Tunnels.Israeli officials claim to have uncovered approximately ninetytunnels in Rafah since 2000, giving the impression of a vast and burgeoningunderground flow of arms into Gaza. When pressed about these claims, the IDFadmitted the figure refers to tunnelentrance shafts,some of which connect to existing3HUMAN RIGHTS WATCH VOL., NO. ()

tunnels and others of which connect to nothing at all. Rather than digging newtunnels, an IDF spokesman told Human Rights Watch, smugglers are often trying toconnect to cross-border tunnels that already exist. This is possible in part because,until 2003, the IDF did not seek to close the tunnels themselves, but merelydemolished the Rafah homes in which tunnel entrance shafts – operative orinoperative – were found. This tactic caused much destruction and homelessnesswhile leaving tunnels largely intact. Since 2003, soldiers are venturing inside tunnels,though an IDF spokesman told Human Rights Watch that the military does nothave the technology to collapse lateral portions of tunnels. In response to aninquiry from Human Rights Watch, the IDF refused to specify how many tunnelsversus entrances had been discovered and destroyed. The IDF’s approach –namely, the use of ineffective methods for two years, followed by unclearimprovements – contrasts sharply with alarmist Israeli statements on tunnels andthe flow of arms.Inoperative Tunnels.In at least three cases, the IDF has destroyed houses containinginoperative tunnels. In July 2004, residents discovered and reported to the PNA anincomplete shaft in an empty house. A few days later, the IDF destroyed the houseand seventeen other houses nearby, leaving 205 people homeless as well as a factory.Human Rights Watch’s onsite assessment just after the incursion, as well asinterviews with eyewitnesses and a representative of a Palestinian armed group,indicated that the destruction was militarily unnecessary; even in the home with thetunnel entrance, demolition of the whole house was an excessive response to anincomplete shaft that could have been effectively sealed with concrete. HumanRights Watch documented two other cases in which the IDF appears to havedestroyed houses with tunnel shafts that had already been sealed by the PNA. TheIDF claims that PNA closures are incomplete.Alternatives to Home Demolition.According to tunnel experts consulted by HumanRights Watch, a number of less destructive alternatives exist for the effectivedetection and destruction of smuggling tunnels. No one method is guaranteed towork in all situations, but different techniques can compensate for each other’sshortcomings, and overall conditions in Rafah favor the IDF: Only four kilometersof the border run alongside Rafah, and tunnel depth is limited by the water table –approximately forty-five meters in the camp. In this environment, the IDF couldinstall an array of underground seismic sensors along the border. Known as a“underground fence,” which has successfully detected digging activity on the U.S.-Mexico border. Other methods, such as electromagnetic induction and ground-penetrating radar, could be used to detect tunnels at the point where they cross theIDF-controlled border, and detection is more likely if the tunnels contain electricalwires, lights, and pulley mechanisms, as the IDF claims. Once the IDF detectstunnels underneath the border, it could dig down and neutralize them with concreteor explosives, obviating the need for incursions into Rafah that result in destroyedhomes and sometimes loss of life.

HUMAN RIGHTS WATCH VOL., NO. ()

4

Israel in all likelihood has access to such sophisticated technology, eitherdomestically or through the U.S. government, its closest ally. But the IDF insists ithas exhausted all alternatives, and that the current tactics are the only effective wayof dealing with the tunnel threat. Despite three requests from Human RightsWatch, the IDF declined to explain the alternative methods it has attempted todetect tunnels and why they did not work. While some information regardingtunnels may be sensitive, the enormous impact on the civilian population ofdemolitions places the burden on Israel to make the case as to why the only way ofdealing with tunnels that run underneath IDF positions is to demolish housesdeeper and deeper into the camp.

Protecting the BorderRafah is one of the most violent areas in the Occupied Palestinian Territories. Over the pastfour years, the IDF and Palestinian armed groups have regularly exchanged fire at variouspoints along the border.What follows is a brief description of the fighting on the borderrather than a chronology of how it unfolded.IDF positions fire with large caliber machine guns and tanks at civilian areas. Based onmultiple visits to the area by Human Rights Watch since 2001 and interviews with localresidents and foreign diplomats, aid workers, and journalists, this shooting appears to belargely indiscriminate and in some cases unprovoked. In July 2004, nearly every house onRafah’s southern edge was pockmarked by heavy machine gun, tank, and rocket fire on theside facing the border. Bullet holes were not only clustered around windows or otherpossible sniper positions, but sprayed over entire sides of buildings. Human Rights Watchresearchers also witnessed indiscriminate use of heavy machine gun fire against Palestiniancivilian areas in nearby Khan Yunis, without apparent shooting by Palestinians from thatarea at the time.On a regular basis, IDF positions and patrols on the border come under attack fromPalestinian armed groups using small arms and rocket-propelled grenades. During the threenights in July Human Rights Watch researchers spent in Rafah, Palestinian small arms firewas sporadic while IDF heavy machine guns fired long bursts into the camp.Representatives of Palestinian armed groups in Rafah told Human Rights Watch that theIDF-controlled border is well-fortified and attacking it is largely in vain, especially because asingle 7.62 mm bullet in Rafah costs U.S. $7 (a figure also cited by the IDF as evidence oftheir success in blocking arms).Both the IDF and Palestinian armed groups use tactics that place civilians at risk. Undercustomary international law, civilians must be kept outside hostilities as far as possible, andthey enjoy general protection against danger arising from hostilities. Human Rights Watchdocumented multiple cases where the IDF converted civilian buildings into sniper positions

5

HUMAN RIGHTS WATCH VOL., NO. ()

during incursions and forced residents to remain with them inside. In some cases, the IDFcoerced civilians to serve as “human shields” while searching Palestinian homes, a practicestrictly prohibited by international humanitarian law.5By attacking the IDF from withinpopulated areas, Palestinian armed groups also place civilians at risk, but Human RightsWatch found no evidence that gunmen fire from inhabited homes or force residents to letarmed groups use their homes.Despite the intense daily gunfire, most homes at the edge of the camp are still inhabited, atleast part of the time. Some residents remain despite the risk, lest the IDF consider theirhomes abandoned and target it for destruction. Even when they do leave, however, absencedoes not constitute abandonment, especially when indiscriminate IDF shooting forcescivilians to flee. One Palestinian, living in the municipal stadium after the IDF bulldozedtwo of his homes in 2001 and 2004, explained how IDF tactics force Palestinians near theborder to leave their homes. “If [the Israelis] want to make you leave the home, they shootthe walls, they shoot the windows,” he said. “Then they can come and say ‘It is empty,’ andbulldoze the house.”6

Comprehensive statistics on combatant and civilian deaths are unavailable and there isno consensus on how many Palestinian casualties from IDF fire are civilians. The IDFdoes not appear to keep statistics of civilian deaths or injuries inflicted by its forces.Accordingto the Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics, 393 residents of the Rafahgovernorate were killed between September 29, 2000, and August 31, 2004, including ninety-eight children under age eighteen.7The lowest possible percentage of civilian victims inRafah is twenty-nine, which is the percentage of women and children killed over the pastfour years. The actual figure is undoubtedly much higher because twenty-nine percentpresumesthat every adult Palestinian male killed was directly participating in hostilities.In the same period, Palestinian armed groups killed ten Israeli soldiers in Rafah. One waskilled while patrolling the border, in February 2001; four others were killed during incursionsinside the camp. The other five soldiers were killed on May 12, 2004, when Islamic Jihadfighters destroyed an Israeli armored vehicle with a rocket-propelled grenade.8The IDFinvoked this latter incident to justify the further expansion of the buffer zone throughwholesale demolition of homes. As discussed below, it better demonstrates the effects ofthe IDF’s expansive notion of security.

5

Human Rights Watch has extensively documented this practice in recent years. SeeIn a Dark Hour: The Useof Civilians During IDF Arrest Operations(Human Rights Watch, April 2002).Human Rights Watch interview with Ibrahim Abu Shittat, Rafah, July 13, 2004.

67

Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics,http://www.pcbs.org/martyrs/table1_e.aspx,(accessed October 4,2004).Figures on Israeli fatalities are drawn from the website of the Israeli Ministry of Foreign Affairs,www.mfa.gov.il.(accessed October 4, 2004) In response to an inquiry from Human Rights Watch, the IDF did not disclosefigures on injuries in Rafah.

8

HUMAN RIGHTS WATCH VOL., NO. ()

6

In this context, the IDF has taken steps that go far beyond what international law allows andwhat the security of its forces requires. The IDF has built improved fortifications on theborder that by themselves would contribute greatly to the protection of patrols; but thesenew fortifications were placed deeper inside the demolished area, bringing them closer to thehouses, and effectively creating a new starting point for demolitions. The IDF’s expansivenotion of security erodes the spirit of international humanitarian law and is a recipe forongoing demolitions.The border between the Gaza Strip and Egypt is 12.5 kilometers long, of which fourkilometers run alongside Rafah. The IDF refers to this border area as the “Philadelphi”corridor or zone, but it is better understood as two distinct areas: a shieldedpatrol corridor(between the border and IDF fortifications) and abuffer zone(the space between IDFfortifications and the houses of Rafah). The expansion of both of these areas is illustrated inthe satellite imagery included in this report.Before the uprising, the IDF maintained a patrol corridor along the border some twenty toforty meters wide, separated from the camp in most places by a concrete wall, approximatelythree meters high, topped with barbed wire. In some areas, especially the densely populatedBlock O section of the camp, houses were situated within several meters of the patrolcorridor.Beginning in 2001, as armed clashes erupted in the border area, the IDF launched nighttimeraids in Block O and other areas of Rafah, demolishing up to one or two dozen homes ineach attack and expelling all residents from the cleared area. The IDF argued that thesedemolitions were necessary responses to attacks from Palestinian armed groups, as well aspart of anti-tunneling efforts. These demolitions resulted in a de facto buffer zone betweenthe patrol corridor and the camp, littered with rubble and empty of Palestinians.By late 2002, after the destruction of several hundred houses in Rafah, the IDF beganbuilding an eight meter high metal wall along the border. This wall, now 1.6 kilometers long,faces the parts of Rafah that used to be closest to the border. Such a structure would havegreatly enhanced the security of IDF patrols by allowing armored vehicles to patrol withoutbeing seen by Palestinian snipers, while fortified IDF towers in the patrol corridor and builtalong the wall could monitor and respond to attacks on the wall from Rafah. Other securitymeasures permitted under international law, such as restricting access to areas near the wallor taking control of property9along it (i.e. seizing homes and closing them off in a reversiblemanner), could have supplemented these moves. Instead of attempting any of thesemeasures, the IDF resorted to demolitions en masse, without warning, often in the middle ofthe night.

While major militaries affirm the right of an occupying power to temporarily control property for securitypurposes, confiscation (permanent seizure and transfer of ownership) is prohibited by Article 46 of the HagueRegulations.

9

7

HUMAN RIGHTS WATCH VOL., NO. ()

Most importantly, the IDF built the wallinsidethe demolished area, some eighty to ninetymeters from the border. Such an expansion doubled the width of the patrol corridor andwas not required to safeguard the border, as the previous twenty to forty meter-wide patrolcorridor was amply wide enough for multi-lane use by armored vehicles. The IDF’s Merkavatank is 3.72 meters wide, while Caterpillar D9 armored bulldozers, used in demolitionoperations, are 4.58 meters wide without armor.The expansion of the patrol corridor brought IDF fortifications closer to the camp,exposing them to risks subsequently invoked to justify further demolitions. According tosatellite imagery taken in May 2004, some two hundred meters of demolished housesseparated the metal wall from the last rows of remaining houses. In total, some fifteenpercent of central Rafah’s pre-2000 built-up area has been razed in order to make way forthe expansion of both the patrol corridor and the buffer zone. The IDF invoked the deathof five Israeli soldiers in Rafah on May 12, 2004, to demonstrate the need for a wider bufferzone. This incident instead illustrates the effects of Israel’s inherently expansive notion ofsecurity: the armored vehicle carrying the soldiers was conducting an anti-tunnelingoperation between the metal wall and the camp, not inside the patrol corridor.According to this logic, the IDF could continue to relocate its positions progressively closerto homes and then destroy them for security purposes. This explains in part why the rate ofhouse demolitions in Rafah tripled in 2003 compared to the previous two years, after thecompletion of the wall, even though it should have reduced the perceived need to protectthe border. Similarly, the IDF’s recommendations for further razing are based in part on theperceived need to safeguard a proposed anti-tunneling trench in the buffer zone. While sucha trench in theory could be lawful, it cannot be invoked as a reason to further expand thebuffer zone, especially in light of the existence of less destructive methods to detect andneutralize tunnels.This inherently expansive notion of “security” is incompatible with Israel’s duty as anOccupying Power to balance its own interests against those of the civilian population. Asone IDF officer put it, “I have no doubt that the clearing actions [i.e. house demolition andland razing] have an element of tactical value, but the question is, where do we draw the line?According to that logic, what prevents us from destroying Gaza?”10

Rampage in Rafah: May 2004In May 2004, Rafah witnessed a level of destruction unprecedented in the current uprising,resulting in 298 demolished homes. After Islamic Jihad destroyed the armored personnelcarrier (APC) on May 12, the IDF launched a two-day incursion to recover the soldiers’remains. IDF tanks and helicopters also led an assault on Block O, reportedly killing fifteen10

Avihai Becker, “The Black List of Captain Kaplan,”Ha’aretz,April 27, 2001, cited in B’tselem,Policy ofDestruction: House Demolitions and Destruction of Agricultural Land in the Gaza Strip,February 2002, p. 34.

HUMAN RIGHTS WATCH VOL., NO. ()

8

Palestinians, including one fifteen-year-old. Six others were identified as combatants.11Claiming that it came under intense fire during the entire operation, the IDF razed eighty-eight homes in Block O and neighboring Qishta area, including houses that had beenseparated from the buffer zone by three or four rows of homes and could not have beenused to fire at the APC or the recovery teams. Towards the end of the incursion, two Israelisoldiers in Qishta were killed by Palestinian snipers.From May 18-24, the IDF conducted a major assault called “Operation Rainbow” thatpenetrated deep into two areas of Rafah – Tel al-Sultan in the northwest and the Brazil andSalam neighborhoods in the east – reportedly leaving thirty-two Palestinian civilians dead,including ten people under age eighteen, as well as twelve armed men. The IDF alsodestroyed 166 houses. The offensive was ostensibly aimed at searching for smugglingtunnels, killing or arresting suspects, and eliminating “terrorist infrastructure.” The IDFclaimed to have discovered three smuggling tunnels during the operation, though lateradmitted that one of these was an incomplete shaft and another was outside of Rafah andnot linked to any house demolitions.In investigating the events of May 2004 and other demolitions, Human Rights Watchdocumented systematic violations of international humanitarian law and gross human rightsabuses by the Israeli military. During the major May incursions of May 18-24, the IDFdestroyed houses, roads, and large fields extensively without evidence that the destructionwas in response to absolute military needs, including in areas of Rafah far from the border.In areas of Brazil further from the border, where incursions were not expected, most of theresidents were inside their homes as armored Caterpillar D9 bulldozers crashed through thewalls. Bulldozers allowed residents to flee but proceeded with the destruction before theycould remove their belongings. In some cases away from the border, like the Rafah zoo, thedestruction took place after the IDF had secured the area, in a manner that was time-consuming, deliberate, and comprehensive, rather than in the heat of battle.The IDF claims its forces came under attack from Palestinians using anti-tank weapons,explosives, and small arms. Based on interviews with thirty-five Rafah residents and twomembers of Palestinian armed groups, information provided by the IDF, public statementsby Palestinian armed groups and the Israeli government, and after surveying the affectedareas, Human Rights Watch believes that armed Palestinian resistance to the May 18-24operation was light, limited, and quickly overwhelmed within the initial hours of eachincursion. Both sides made tactical choices to maximize their respective advantages: theIDF limited their operations mostly to Brazil and Tel al-Sultan, where they were notexpected and Palestinian armed groups laid ambushes in the densely populated heart of theoriginal camp, where they would be more likely to engage the IDF at close quarters. Assatellite images in this report ff Tel al-Sultan and Brazil show, the main streets in these two

Because in this investigation HRW focused on the pattern of property destruction, figures on deaths werecompiled from an analysis of reporting by local human rights organizations, media accounts, and statements byPalestinian armed groups, supplemented in some cases by Human Rights Watch’s own documentation.

11

9

HUMAN RIGHTS WATCH VOL., NO. ()

areas are relatively wide and arranged in grid-like patterns. The Israeli government designedthem in this way during the 1970s to facilitate the movement of its forces and limit cover forPalestinian gunmen. As a result, throughout the operation there was minimal directengagement between the IDF and Palestinian armed groups. This contrasts sharply with thefierce multi-day battle in the densely populated heart of Jenin refugee camp in April 2002,which resulted in the death of fifty-two Palestinians, including twenty-seven confirmedcivilians, and thirteen IDF soldiers.During the incursions into Tel al-Sultan and Brazil, the IDF employed armored CaterpillarD9 bulldozers in a manner that was indiscriminate and excessive, resulting in widespreaddestruction of homes, roads, and agriculture that could have been avoided:Houses.In Brazil, Caterpillar D9 bulldozers cleared “tank paths” inside the camp byplowing through blocks of houses as a general precaution against possible attackswith RPGs or roadside bombs, irrespective of the specific threats that internationallaw requires. The IDF also used D9s to destroy homes near suspected smugglingtunnels and in other areas on a preventive basis, not in response to specific threats.Other house demolitions had no discernible reason.Road destruction.In both Tel al-Sultan and Brazil, the IDF used Caterpillar D9s toindiscriminately tear up roads, destroying water and sewage networks, and creating asignificant public health risk in an already vulnerable community. In some areas,water shortages forced residents to leave their homes in search of water, puttingthem at risk of being shot by IDF snipers for breaking curfew. In total, the IDFdestroyed fifty-one percent of Rafah’s roads, usually by dragging a blade known asthe “ripper” from the back of the D9 down the middle of the road. The IDF gavevarious explanations for this tactic, including the need to clear paths of potentialbombs (improvised explosive devices, or IEDs), to sever wires that could be used todetonate explosive devices and to prevent suicide car attacks on Israeli forces. If theIDF was truly concerned about wires and IEDs, it would have used a frontmounted device. Instead they usedrear-mountedrippers that afforded noprotection for the D9 bulldozers or their drivers from explosive devices in the road.In addition, as a photograph in Chapter 6 taken from another incursion shows, theripper creates a path of debris down the middle of the road, leaving side lanes intactfor use by suicide car attacks. And tearing up paved roads creates loose debris thatfacilitates the concealment of explosives and booby-traps.Razing Agricultural Land.The IDF razed two large tracts of agricultural land outsidethe Tel al-Sultan housing project away from the border. Such destruction after theIDF had secured the area was disproportionate to any potential military gain andhad a harmful impact on an area where agricultural production plays an importantrole. The IDF told Human Rights Watch that military vehicles destroyedagricultural land because they had to avoid booby-traps on roads, but this does not

HUMAN RIGHTS WATCH VOL., NO. ()

10

explain why bulldozers spent more than two days systematically destroying two largefields of greenhouses.While research focused on the extensive destruction in the Rafah camp, Human RightsWatch also documented other abuses during the incursions into Tel al-Sultan and Brazil,including unlawful killings of civilians and IDF troops coercing civilians to serve as “humanshields.” Most egregiously, on March 19, an Israeli tank and helicopter opened fire on ademonstration, killing nine, including three children under age eighteen. The IDF did notclaim that its troops had come under fire, only that gunmen were in the crowd; eyewitnessaccounts and video evidence contradict this. In response to an inquiry from Human RightsWatch, the IDF said that one those killed had been listed in its records as a “Hamas activist”but did not substantiate or even reaffirm the claim that he had been armed at the time.

Doctrines of DestructionAs the Occupying Power in the Gaza Strip, the IDF has two roles: an administrator withpolice and security powers, and a potential belligerent who may engage in fighting. But atalltimes it is responsible for protecting the civilian population, in accordance with bothinternational humanitarian law (the laws of armed conflict) and human rights law.International humanitarian law permits an occupier to take the drastic step of destroyingproperty only when “rendered absolutely necessary by military operations.”12According tothe International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC), military operations are “movements,manœuvres and actions of any sort, carried out by the armed forces with a view tocombat.”13A belligerent occupation cannot be considered a “military operation” in itself,nor can every activity conducted by the Occupying Power be considered a militaryoperation; rather, a military operation must have some concrete link to actual or anticipatedfighting. Destroying property to improve the general security of the occupier or as a broadprecaution against hypothetical threats is prohibited. As the ICRC stated during the Mayincursions in Rafah, “the destruction of property as a general security measure isprohibited.”14Even during military operations, indiscriminate and disproportionate attackson civilian objects are not allowed. Civilian property may not be destroyed unless it ismaking an effective contribution to military action and its destruction offers a definitemilitary advantage. In cases in which the targeted object is normally dedicated to a civilianpurpose, such as a house, the presumption under the law is that it is not a legitimate target.

1213

Fourth Geneva Convention, Art. 53.

ICRC, Commentary to the Protocol Additional to the Geneva Conventions of 12 August 1949, and relating tothe Protection of Victims of International Armed Conflicts (Protocol I), 8 June 1977, p. 67. See virtually identicallanguage in “Interpretation by the ICRC of Article 53 of the Fourth Geneva Convention of 12 August 1949, withparticular reference to the expression ‘military operations,’” Letter to al-Haq signed by Jacques Moreillon,Director of Department of Principles and Law and Jean Pictet, ICRC, November 25, 1981 (“… with a view tofighting”) and “Occupation and international humanitarian law: questions and answers,” ICRC press release,August 4, 2004 (“…when absolutely required by military necessity during the conduct of hostilities”).14

“ICRC Deeply Concerned Over House Destructions in Rafah,” ICRC press release, May 18, 2004.

11

HUMAN RIGHTS WATCH VOL., NO. ()

Outside of combat, the Occupying Power may take measures to enhance its security.Among other things, it can temporarily take control of property to prevent its hostile use,build fortifications, and prohibit access to certain areas, but these measures must becompatible with a fuller range of human rights protections, including the right tocompensation for properties seized. Although it has denied the applicability of internationalhuman rights instruments to Palestinians in the OPT, Israel is widely considered to be boundby these laws. International human rights law obliges Israel to provide effective judicialremedies for victims of forced eviction and to ensure adequate housing for PalestiniansThe IDF’s unlawful policy of destruction is consistent with public statements by Israeliofficials, the IDF’s disturbingly permissive interpretation of international law, and its ownadmission that destruction has been excessive:The IDF has publicly admitted destroying houses to “weaken the fear of tunnels”15or in response to other hypothetical risks. This doctrine conflates the legalrequirement of absolute military necessity – a strict standard requiring that anyproperty destruction must be connected to combat – with the much broader notionof security. This conflation is consistent with the expressed desire of senior IDFofficers, from Sharon’s days as head of the IDF Southern Command in the early1970s16through Yom-Tov Samiya’s statements quoted at this summary’s beginning,to raze all homes near the border.The IDF’s military manual misinterprets international law to permit destructioneven when it violates the laws of armed conflict, a standard that is far morepermissive than that of other major militaries. According to the IDF manual, “TheHague Conventions state that unnecessary destruction of enemy property isforbidden. … The only restriction is to refrain from destroying property senselessly,where there is no military justification, for the sheer sake of vandalism.”17The IDFmanual does not mention that military necessity is commonly understood amongmajor militaries to exclude actions that are expressly prohibited by the rules of IHL,since military necessity was incorporated into the formulation of those rules.18The

“Transcript of GOC Southern Command Regarding the Findings of the Investigation of the Demolition of theBuildings in Rafah (10-11.01.02),” IDF Spokesperson’s Unit, January 27, 2002.Sharon wrote in his memoirs that “it was essential to create a Jewish buffer zone between Gaza and the Sinai[then under Israeli control] to cut off the flow of smuggled weapons and – looking forward to a future settlementwith Egypt – to divide the two regions” (Warrior:The Autobiography of Ariel Sharon(New York: Simon &Schuster, 2001), p. 258).1716

15

Laws of War in the Battlefield(IDF Military Law School, Department of International Law, 1998), p. 69. Themanual is available in English athttp://www.ihlresearch.org/opt/bounce.php?a=12623,(accessed October 4,2004).

18

See,inter alia, U.S. Army Field Manual 27-10: The Law of Land Warfare(Department of the Army, July1956), p. 4;The Manual of the Law of the Law of Armed Conflict(Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004), pp.21-23;The Law of Armed Conflict at the Operational and Tactical Level(Office of the Judge Advocate General,Canadian military, September 2001), section 2-1.

HUMAN RIGHTS WATCH VOL., NO. ()

12

manual also does not require that property destruction be absolutely necessary orthat it conform to fundamental principles of IHL, such as the duty to refrain fromindiscriminate or disproportionate attacks. The IDF manual is far more permissivethan, for example, the U.S. and Canadian military manuals, which require someconnection between destruction and the overcoming of enemy forces.19Senior IDF officers have admitted that not all property destruction is authorized orjustified in such operations. After the IDF destroyed approximately sixty houses inBlock O in January 2002, Major-General Doron Almog, then head of the SouthernCommand, announced that some of the houses had been inadvertently destroyeddue to “navigational errors.”20Brigadier-General Dov Zadka told the press on oneoccasion that he had approved a particular scope of “clearing,” only to find thattroops had exceeded the approved amount. “You approve the removal of thirtytrees, and the next day you see that they removed sixty trees,” he said.21Even ifthese were mistakes, compensation and/or reparation should be made in such cases.Despite this, the IDF has apparently not investigated any cases of improper orunlawful house demolitions.

Rafah is not the only place where the IDF has extensively destroyed property in the name ofsecurity. Throughout the Gaza Strip, Israeli forces have created buffer zones near IDFbases, illegal settlements, and Israeli-only bypass roads by systematically leveling houses andagricultural fields.22For decades, the IDF has demolished homes for various reasons. Most prominent havebeen punitive – or “deterrent” – demolitions aimed at the family homes of Palestiniansengaged or suspected of engaging in armed activities. Such collective punishments arestrictly forbidden by international humanitarian law.23Israeli authorities have also destroyedPalestinian houses in the West Bank and Israel ostensibly for violating building coderegulations. These demolitions are not the focus of this report but have been extensivelyaddressed elsewhere.24

19

U.S. Army Field Manual 27-10: The Law of Land Warfare,pp. 23-24;The Law of Armed Conflict at theOperational and Tactical Level,section 12-9.

“Transcript of GOC Southern Command Regarding the Findings of the Investigation of the Demolition of theBuildings in Rafah (10-11.01.02),” IDF Spokesperson’s Unit, January 27, 2002, available atweb.archive.org/web/20020805024807/www.idf.il/english/announcements/2002/january/27.stm.21

20

Guy Zadkham, “Zadka under fire,”B’Mahanah[IDF magazine], December 28, 2001, cited in B’tselem,Policyof Destruction: House Demolitions and Destruction of Agricultural Land in the Gaza Strip, p. 29.

See,inter alia,periodic reports on land leveling in the Gaza Strip by the Palestinian Centre for Human Rights,available atwww.pchrgaza.organd B’tselem,Policy of Destruction: House Demolitions and Destruction ofAgricultural Land in the Gaza Strip,February 2002.2324

22

Fourth Geneva Convention, Art. 33.

On punitive demolitions, see,inter alia,al-Haq,Israel’s Punitive House Demolition Policy: CollectivePunishment in Violation of International Law,2003; al-Haq,A Thousand and One Homes: Israel's Demolitionand Sealing of Houses in the Occupied Palestinian Territories,1993; and B’tselem,Demolition and sealing ofhomes in the West Bank and the Gaza Strip as a Punitive Measure During the Intifada,1989. On administrative

13

HUMAN RIGHTS WATCH VOL., NO. ()

Nowhere to TurnPalestinians in the Occupied Palestinian Territories (OPT) have nowhere to turn in Israel forlegal protection against unlawful demolitions and forced evictions. The IDF, the SupremeCourt, and the Knesset have all played a role in denying effective remedies.An IDF spokesman and an IDF legal officer told Human Rights Watch that they had noknowledge of any investigations into cases of unlawful or improper house demolition,25eventhough the IDF military police had opened 173 investigations of damage to property in theOPT as of May 2004 (thirty-four percent of the total number of investigations opened in theOPT).26The Israeli Supreme Court has consistently sanctioned IDF policies that violateinternational law, including house demolitions aimed at collectively punishing families ofmilitants and those destroyed to make way for the illegal “separation barrier” underconstruction inside the occupied West Bank.27And under Israeli law, compensation is ruledout in cases of “combat activity,” which the Knesset amended in 2002 with an expansivedefinition that includes virtually every IDF action in the OPT.The international community has forcefully condemned unlawful destruction in Rafah andelsewhere in the OPT. But donors who have invested heavily in Gaza, including ininfrastructure and facilities destroyed by the IDF, have found themselves entangled in adilemma. On the one hand, the knowledge that international aid money will pay toreconstruct what has been destroyed is likely to fuel the IDF’s sense of impunity forunlawful destruction. On the other hand, donors know that restricting or reducing aidwould harm Palestinian victims. Under international law, Israel is responsible for unlawfuldamage caused by its forces and cannot misuse aid meant for Palestinians to evade its ownobligations. As such, Human Rights Watch recommends that the international communitypress Israel to either pay reparations to victims or to compensate donors directly for anyfunds spent on repairing unlawful destruction.

MethodologyA Human Rights Watch team of three researchers spent a combined total of one month inthe Gaza Strip, Israel, and Egypt to research this report. The team interviewed over eightyindividuals, including thirty-five residents of Rafah who were victims of and/or eyewitnesses

demolitions in East Jerusalem, see B’tselem,A Policy of Discrimination: Land Expropriation, Planning andBuilding in East Jerusalem,1995.Human Rights Watch interviews with Major Assaf Librati, Spokesman, IDF Southern Command, Tel Aviv, July25, 2004 and Major Noam Neuman, IDF Deputy Legal Adviser for the Gaza Strip, Tel Aviv, July 20, 2004.262725

IDF correspondence with HRW, May 10, 2004.

See,inter alia,International Court of Justice, “Advisory opinion on Legal Consequences of the Construction ofa Wall in the Occupied Palestinian Territory,” July 9, 2004 and “Israel’s ‘Separation Barrier’ in the OccupiedWest Bank: Human Rights and International Humanitarian Law Consequences,” Human Rights Watch,February 2004.

HUMAN RIGHTS WATCH VOL., NO. ()

14

to house demolitions or other abuses, corroborating and cross-checking their accounts.Researchers also spoke to first-hand participants in and observers of events in Rafah,including representatives of two Palestinian armed groups, Palestinian National Authoritysecurity personnel, and municipal officials. Representatives of international relieforganizations and local human rights groups in Gaza City also provided information.In Israel, the researchers met with three representatives of the IDF and an official from theIsraeli Ministry of Foreign Affairs, as well as foreign diplomats, military specialists, local andinternational journalists, and local human rights organizations. The IDF shared informationabout its operational and legal doctrines, as well as its unclassified assessments of the Rafahborder situation. In Egypt, researchers met with officials from the Egyptian InteriorMinistry, local activists, and journalists. The research also included analysis of publicstatements by Israeli government entities and Palestinian armed groups.Human Rights Watch also conducted on-site examination of physical evidence in Rafah,including ballistics, especially in cases of recent demolitions. In all cases, researchersrecorded the precise Global Positioning System (GPS) coordinates of locations visited,including those of demolished houses, using handheld GPS devices. The geospatial data hasbeen incorporated into the maps and satellite images in this report. Researchers tookhundreds of digital photographs, some of them reproduced in this report, and were givenaccess to extensive photographs and video taken by local journalists and human rightsorganizations during the May 2004 incursions.In analyzing the broader patterns of destruction, Human Rights Watch was aided by satelliteimagery of Rafah taken since 2000 and provided by Space Imaging North America, SpaceImaging Eurasia, Space Imaging Middle East, and DigitalGlobe. Human Rights Watch alsodrew on detailed statistical data on house demolitions compiled by UNRWA and thePalestinian Centre for Human Rights (PCHR).

II. RECOMMENDATIONSTo the Government of IsraelCease all property destruction that is not absolutely necessary to the conduct ofhostilities, including all punitive (“deterrent”) destruction. Prohibit attacks againstproperty on the basis of mere suspicion or hypothetical risk rather than absolutemilitary necessity.Repudiate plans to widen the border (“Philadelphi”) buffer zone, including in theevent of “disengagement” from the Gaza Strip.Allow general return of residents to demolished areas, including in de facto bufferzones. Ensure that any restrictions on return are proportionate in impact andduration, regularly re-evaluated and implemented only when and to the extent

15

HUMAN RIGHTS WATCH VOL., NO. ()

necessary, open to challenge before an impartial court, and accompanied byprovisions for adequate housing.Ensure that any use of armed force, especially along the Rafah border or aroundother Israeli bases, is proportionate and discriminate. Ensure that open fireregulations issued to members of the Israel Defense Force in border fortificationscomply with the U.N. Basic Principles on the Use of Force and Firearms by LawEnforcement Officials and the U.N. Code of Conduct for Law EnforcementOfficials.Investigate and hold accountable all members of the IDF and their superiors foundto have destroyed, or tolerated the destructions of, homes or property in violationof international humanitarian law.Pay reparations and full compensation to owners of unlawfully demolished homes.If funds for repairing unlawful damage caused by the IDF are allocated byinternational donors, compensate donors directly.Ensure that any control of property for security reasons is fully consistent with bothinternational human rights standards and international humanitarian law. Control ofproperty should be used only when and to the extent necessary, should not amountto confiscation, and should be open to challenge before an impartial court.Maintain accurate statistics on property damaged, make that information publiclyaccessible in a timely fashion, and require that such reporting be part of theoperational debrief following any military operation. Such record keeping shouldalso include the precise justification for the demolition, whether it was conducted inthe course of combat activities, and the specific incidents that led to that demolitionor property destruction.Repeal the 2002 amendment to the Torts (State Liability) Law to allow individualswhose property has been wrongfully damaged in IDF operations to claimcompensation.Cease immediately the practice of using lethal force to enforce mass house arrest orcurfew.Cease immediately the practice of indiscriminately destroying roads, as well asassociated destruction of infrastructure.Cease immediately the coerced use of civilians to assist IDF military operations.To the maximum extent feasible, avoid locating military objectives within or neardensely populated areas. Take all necessary precautions to protect the civilianpopulation, individual civilians and civilian objects under IDF control against thedangers resulting from military operations.Allow immediate access to, and cooperate fully with, the human rights specialmechanisms of the United Nations as well as other independent internationalinvestigators, to investigate allegations of human rights violations since thebeginning of the uprising on September 29, 2000.Explain why the IDF is not using less destructive methods of neutralizing tunnels.

HUMAN RIGHTS WATCH VOL., NO. ()

16

To the Palestinian National AuthorityInstruct the law enforcement agencies of the PNA to take all possible steps, inaccordance with internationally accepted human rights norms, to identify and bringto justice anyone who incites, plans, assists, or attempts to carry out attacks againstcivilians.Take all possible steps to restrict the flow of arms used in attacks against civilians.Discourage Palestinian armed groups from launching attacks from civilian areas.Map accurately and comprehensively the exact location, nature, and value ofproperties and agricultural land destroyed by the IDF.

To Palestinian armed groups in RafahCease deliberate attacks against civilians and civilian targets.Cease use of inherently indiscriminate weapons. These include rockets that cannotbe aimed and victim-activated explosive devices such as booby-traps.To the maximum extent feasible, avoid launching attacks from areas populated bycivilians or locating military objectives within or near densely populated areas. Takeall necessary precautions to protect the civilian population control against thedangers resulting from armed activities.

To the International CommunityDemand that the Government of Israel and the PNA implement the aboverecommendations.Insist that Israel continue to abide by its responsibilities as an Occupying Powerunder international humanitarian law if the partial redeployment envisioned by the“disengagement” plan is implemented.Monitor carefully damage to donor-funded property, projects, or infrastructure inGaza, and ensure that compensation is paid by Israeli authorities for losses ordamage caused in contravention of international law.Insist that Israel compensate donor governments for funds spent on repairingunlawful destruction by the IDF.Fully support programs aimed at ensuring the right to adequate housing of displacedPalestinians.Support the return of Palestinians displaced by unlawful demolitions.High Contracting Parties to the Geneva Conventions of 1949 should takeimmediate action, individually and jointly, to ensure respect for the provisions of theFourth Geneva Convention, including prohibitions on unlawful destruction andcollective punishment.

17

HUMAN RIGHTS WATCH VOL., NO. ()

Provide technical and material support to strengthen the investigative capacity ofthe PNA’s law enforcement agencies including, if necessary and appropriate,through the temporary secondment of suitably qualified police investigators to workalongside Palestinian officers and to assist them in pursuing and bringing to justicethose responsible for attacks against civilians.

To the Government of the United StatesDemand that the Government of Israel and the PNA take immediate steps toimplement the above recommendations in both private and public communications.Restrict Israel’s use of Caterpillar D9 armored bulldozers, Apache and Cobrahelicopter gunships, and other U.S.-origin weapons systems that are used in thecommission of systematic violations of international human rights and humanitarianlaw.Inform the Government of Israel that continued U.S. military assistance requiresthat the government take clear and measurable steps to halt its security forces’serious and systematic violations of international human rights and humanitarian lawin the West Bank and Gaza Strip, as documented in this and previous HumanRights Watch reports.28These steps should include conducting transparent andimpartial investigations into allegations of serious and systematic violations, makingthe results public, and holding accountable persons found responsible.Inform the PNA that any security assistance from the U.S. requires clear andmeasurable steps to halt within its power to halt serious and systematic violations ofinternational human rights and humanitarian law in the West Bank and Gaza Stripby its security forces and by Palestinian armed groups, as documented in previousHuman Rights Watch reports.29Ensure that enforcement of human rights and humanitarian law protections are notmade subordinate to the outcomes of direct negotiations between the parties to theconflict. Agreements should be consistent with fundamental human rights andhumanitarian norms.

To the Member States of the European UnionDemand that the Government of Israel and the PNA take immediate steps toimplement the above recommendations in both private and public communications.

See,inter alia,“Israel's ‘separation barrier’ in the occupied West Bank: Human Rights and InternationalHumanitarian Law consequences” (Human Rights Watch, February 2004),Jenin: IDF Military Operations(Human Rights Watch, May 2002),In a Dark Hour: The Use of Civilians During IDF Arrest Operations(HumanRights Watch, April 2002),Center of the Storm: A Case Study of Human Rights Abuses in Hebron District(Human Rights Watch, April 2001).29

28

See,inter alia, Erased in a Moment: Suicide Bombing Attacks Against Israeli Civilians(Human Rights Watch,October 2002) andJustice Undermined: Balancing Security and Human Rights in the Palestinian JusticeSystem(Human Rights Watch, November 2001).

HUMAN RIGHTS WATCH VOL., NO. ()

18

Consistent with the August 11 declaration of European Commissioner forDevelopment and Humanitarian Aid Poul Nielson, make clear to Israel thatemergency funds for reconstruction in the OPT do not absolve Israel of itsresponsibilities as an Occupying Power under international humanitarian law.Develop and make public benchmarks for compliance by the government of Israelwith international human rights and international law commitments as embedded inArticle 2 of the Euro-Mediterranean Association Agreement between the E.U. andits member states and Israel.Implement the European Code of Conduct on Arms Exports and restrict transferto Israel of weapons found to be used in the commission of serious and systematicviolations of international human rights and humanitarian law in the West Bank andGaza Strip.Inform the PNA that any security assistance from the E.U. requires clear andmeasurable steps to halt within its power to halt serious and systematic violations ofinternational human rights and humanitarian law in the West Bank and Gaza Stripby its security forces and by Palestinian armed groups, as documented in previousHuman Rights Watch reports.Ensure that enforcement of human rights and humanitarian law protections are notmade subordinate to the outcomes of direct negotiations between the parties to theconflict.

To Caterpillar Inc.Suspend sales of D9 bulldozers, parts, or maintenance services to the IDF pendingthe implementation of the above recommendations.Seek to ensure that Caterpillar’s goods and services will not be used to abuse humanrights, in accordance with the U.N. Norms on the Responsibilities of TransnationalCorporations and Other Business Enterprises with Regard to Human Rights.

III. BACKGROUNDThe Gaza Strip is a wisp of land southwest of Israel along the Mediterranean Sea. Forty-fivekilometers long and ranging from five to twelve kilometers wide, it is home to some 1.2million Palestinians, making it one of the most densely populated areas on Earth.Approximately seventy-eight percent of the Palestinian population consists of refugees,displaced in 1948 and 1949 from what is now Israel, and their descendants.The Gaza Strip and West Bank were the two areas of the British mandate of Palestine thatdid not become part of the new state of Israel as a result of the 1948 Arab-Israeli war.Instead, Gaza came under Egyptian control while Jordan seized the West Bank. Israelbriefly took Gaza and the Sinai peninsula during the Suez Crisis in 1956, but returned themto Egypt under international pressure. The 1967 War, however, left Israel in control of

19

HUMAN RIGHTS WATCH VOL., NO. ()

Gaza, the West Bank, the Sinai, and the Golan heights of Syria. In 1982, Israel returned theSinai to Egypt as part of the Camp David Peace Treaty. The U.N. refers to the West Bankand Gaza Strip as the Occupied Palestinian Territories (OPT).Under international law, Gaza, the West Bank, and the Golan are occupied territories, whichplaces their populations under the protection of the Fourth Geneva Convention. Israel haslong disputed the applicability of the Fourth Geneva Convention to the OPT, although ithas promised to voluntarily abide by its humanitarian provisions. The rest of theinternational community has consistently affirmed the applicability of the Convention to theOPT and Israel’s responsibilities as an Occupying Power under the Convention.30Israel has continually failed to fulfill its obligations under international law as an OccupyingPower. It has built, and continues to build, settlements in the West Bank and Gaza Stripreserved exclusively for Jews. Such settlements in occupied territory are illegal underinternational law; they violate the prohibitions of the transfer of civilians to an occupiedterritory31and the creation of permanent changes that are not for the benefit of the occupiedpopulation. After World War II, the drafters of the Fourth Geneva Convention specificallyintended to prevent states from colonizing territories they occupied.32According to the Oslo Accords of the 1990s, approximately forty percent of Gaza’s territoryis currently under direct Israeli military control, most of it inaccessible to Palestinians.33These areas include some twenty Israeli settlements, home to 7,500 settlers, Israel DefenseForces (IDF) bases, and exclusive by-pass roads linking these areas to each other and toIsrael.34Areas along the Egyptian border in the south and the boundary with Israel in thenorth and east are also under direct Israeli military control. Israel controls all movement intoand out of the Gaza Strip.

These arguments are reviewed in,inter alia, Center of the Storm: A Case Study of Human Rights Abuses inHebron District(New York: Human Rights Watch, April 2001) andIsrael’s Closure of the West Bank and GazaStrip(New York: Human Rights Watch, July 1996). Israeli Attorney General Menachem Mazuz recentlyrecommended that the government “thoroughly examine” the possibility of formally applying the Convention tothe OPT. The recommendation was made after examining the legal consequence of the International Court ofJustice’s July 9 advisory opinion, which found that the parts of Israel’s “separation barrier” built inside the WestBank violate international law and should be dismantled (Aluf Benn, “AG: ICJ Ruling Necessitates Adoption ofGeneva Convention,”Ha’aretz,August 25, 2004). The government has not indicated whether it will reverse itslongstanding policy on the Convention’s applicability in the OPT.3132

30

Fourth Geneva Convention, Art. 49(6).

Jean S. Pictet, ed., Commentary on the Geneva Conventions of 12 August 1949: IV Geneva ConventionRelative to the Protection of Civilian Persons in Time of War (International Committee of the Red Cross:Geneva, 1958), commentary on Art. 49(6) of Fourth Geneva Convention, p. 282.33

See Palestinian Centre for Human Rights,A Comprehensive Survey of Israeli Settlements in the Gaza Strip(undated),http://www.pchrgaza.org/files/S&r/English/study10/Conclusion.htm,(accessed July 27, 2004).Settlement population as of December 31, 2003. See Israeli Central Bureau of Statistics, “Population inUrban Localities and Other Geographic Divisions, Provisional Data as of December 30, 2003,” March 2004.Available athttp://www.cbs.gov.il/population/popul_eng.htm,as of July 27, 2004. Actual settlementspopulations are believed to be lower.34

HUMAN RIGHTS WATCH VOL., NO. ()

20

Map 1: Gaza Overview (Map 1: Gaza Overview) [place opposite pageto the text]The rest of Gaza is administered by the Palestinian National Authority (PNA), headed byYasser Arafat, as dictated by the Oslo Accords of 1994-1995. The PNA is not a sovereignstate but a self-rule administration with policing powers and is subordinate to Israel in bothlaw and practice.35Under the Oslo Accords, Israel retains overall security authoritythroughout the OPT for external defense and can take “all necessary” steps to ensure thesecurity of both Israel and the settlements, including by taking action in areas directlyadministered by the PNA.36Agreements between an Occupying Power and local authoritiescannot be used to deprive civilians of their protections under international humanitarianlaw.37Although the PNA cannot ratify international human rights instruments, it has signaled itsdesire to adhere to human rights standards. Human Rights Watch considers the PNA to bebound to international human rights standards to the extent of its powers, includingobligations to prevent attacks against civilians from areas under its control and to respect thehuman rights of individuals in its custody. The PNA has continually failed to fulfill theseobligations.38The PNA has no military but has several security forces, from regular police to intelligenceservices. There are also a number of Palestinian armed groups in the Gaza Strip which areoutside of the PNA’s authority and sometimes in adversarial relationships with it. Armedgroups active in Gaza include the al-Aqsa Martyrs Brigade, a militant offshoot of Arafat’sFatah party, and the military wings of Hamas, Islamic Jihad, the Popular ResistanceCommittees, and the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine. In their fight against theoccupation, all of these groups attack both civilian and military targets. Targeting civilians orcarrying out indiscriminate attacks against them violates international humanitarian law, andHuman Rights Watch has documented and condemned the practice by Palestinian armedgroups.39International organizations and local nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) are alsoinvolved in all aspects of Gaza life. Most important is the United Nations Relief and WorksAgency (UNRWA) for Palestine Refugees in the Near East, whose mandate includes theprovision of social services such as health care and education to Palestinian refugees both35363738

See Human Rights Watch,Israel’s Closure of the West Bank and Gaza Strip,July 1996.Israeli-Palestinian Interim Agreement (“Oslo II”), 1995, Art. XII(1).Fourth Geneva Convention, Art. 47.

See Human Rights Watch,Justice Undermined: Balancing Security and Human Rights in the PalestinianJustice System,November 2001 andErased in a Moment: Suicide Bombing Attacks Against Israeli Civilians,October 2002See Human Rights Watch,Erased in a Moment: Suicide Bombing Attacks Against Israeli Civilians,October2002.

39

21

HUMAN RIGHTS WATCH VOL., NO. ()

inside and outside officially recognized refugee camps. UNRWA also provides emergencyrelief. The agency’s role in providing services in the Gaza Strip rivals that of the PNA, aseighty percent of Gaza’s population consists of refugees. Palestinian NGOs are also veryactive in the fields of health care, education, and human rights.

The Uprising in Gaza: From Closure to “Disengagement”Over the past four years, Israel has faced an armed uprising throughout the OPT, includingattacks on both its military and civilians. In the Gaza Strip, the government has respondedwith a broad strategy of isolating the Palestinian population from Israel, strictly controllingthe movement of Palestinians, while attempting to retain overall control over the territory.As explained below, the so-called “Gaza disengagement plan” is a continuation of thisprocess.The fighting has taken a heavy toll in the Gaza Strip, where patterns of fatalities differconsiderably from the uprising as a whole. Since 2000, roughly three times as manyPalestinians have been killed as Israelis in total; within Gaza, however, the ratio is closer toten to one. According to the Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics, 1,642 Palestinians werekilled in the Gaza Strip between September 29, 2000, and August 31, 2004, including 360children under the age of eighteen.40As of September 24, 113 Israelis (eighty-five soldiers orarmed guards and twenty-eight civilians) had been killed by Palestinians in the Gaza Strip,while fifteen civilians within Israel proper had been killed by attacks originating from theGaza Strip.41And while members of security forces account for approximately one-third ofall Israeli deaths in the uprising,42the eighty-two soldiers and armed guards killed in the GazaStrip represent seventy-five percent of Israeli fatalities there.The primary Israeli method for dealing with the uprising has been the tightening of“closure” policies that date back to the early 1990s.43“Closure” is a broad termencompassing many different restrictions on freedom of movement, from preventinginternational travel to placing checkpoints on roads between neighboring villages toimposing twenty-four hour curfews that amount to mass house arrest. Closure policies inand around the Gaza Strip are far more hermetic than those in the much larger West Bank;they have also been more pervasive than overtly violent policies such as bombardment,assassination of militants and political leaders, and property destruction.4041

Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics,http://www.pcbs.org/martyrs/table1_e.aspx.

The figures do not include four foreign workers and three U.S. diplomats but do include Arab IDF soldiers.Israeli Ministry of Foreign Affairs, “Victims of Palestinian Violence and Terrorism since September 2000,”available athttp://www.mfa.gov.il/MFA/Terrorism-+Obstacle+to+Peace/Palestinian+terror+since+2000/Victims+of+Palestinian+Violence+and+Terrorism+sinc.htm,as of September 23, 2004.According to statistics compiled by the Israeli human rights group B’tselem, thirty-one percent of Israelis killedby Palestinian residents of the OPT during the conflict up to August 31, 2004 were members of security forces(http://www.btselem.org/English/Statistics/Al_Aqsa_Fatalities.asp, accessed September 18, 2004).4342

For an analysis of the closure regime during the Oslo process, see Human Rights Watch,Israel’s Closure ofthe West Bank and Gaza Strip,July 1996.

HUMAN RIGHTS WATCH VOL., NO. ()

22