Europaudvalget 2009-10

EUU Alm.del Bilag 18

Offentligt

May 2009

Eleventh Bi-annual Report:Developments in European UnionProcedures and PracticesRelevant to Parliamentary Scrutiny

Prepared by the COSAC Secretariat and presented to:XLI Conference of Community and European AffairsCommittees of Parliaments of the European Union11-12 May 2009Prague

Conference of Community and European Affairs Committees of Parliamentsof the European Union

COSAC SECRETARIATRMD 02 J 032, 89 rue Belliard, B-1047 Brussels, BelgiumE-mail:[email protected]| Fax: +32 2 230 0234

2

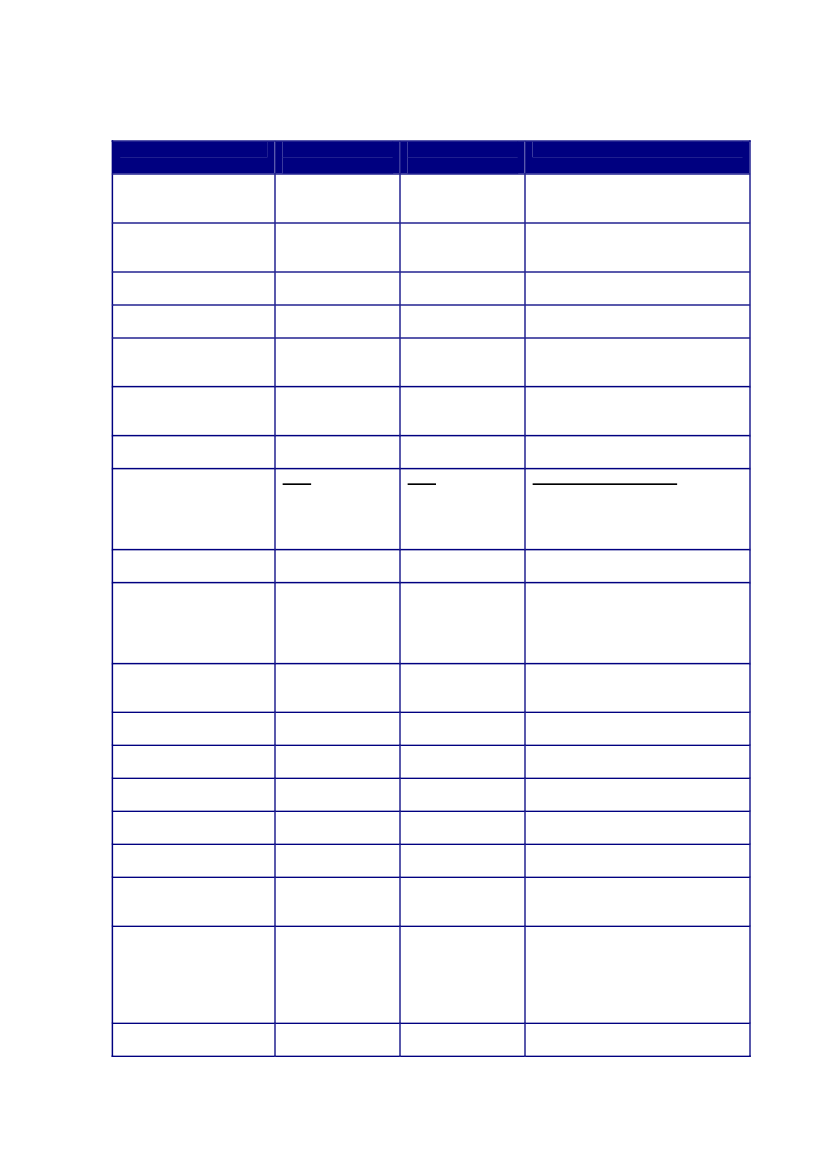

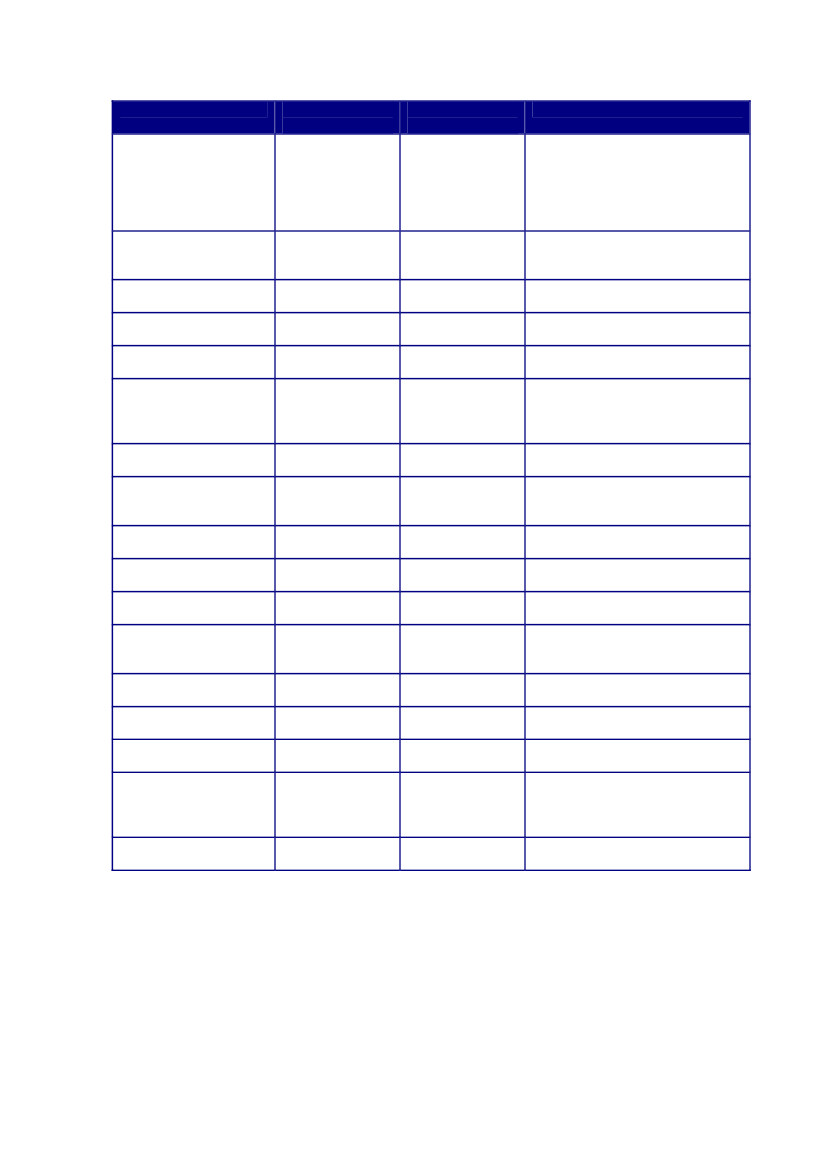

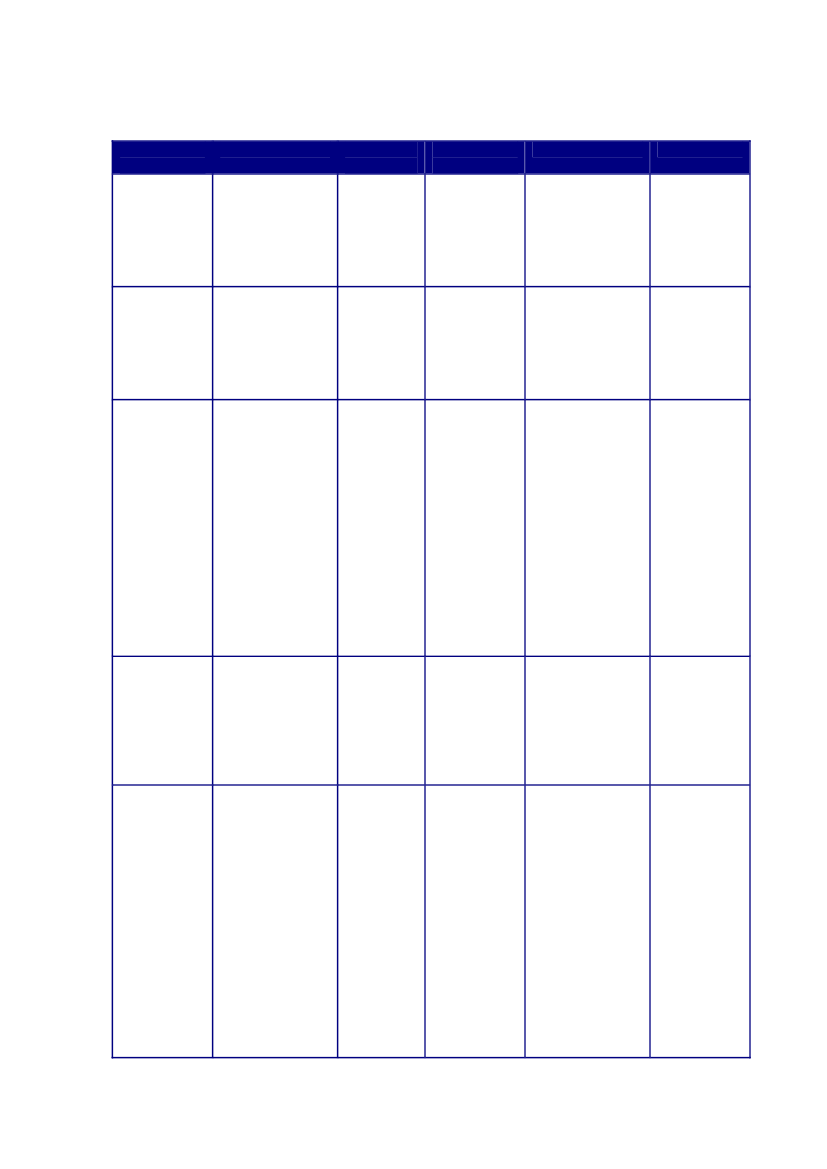

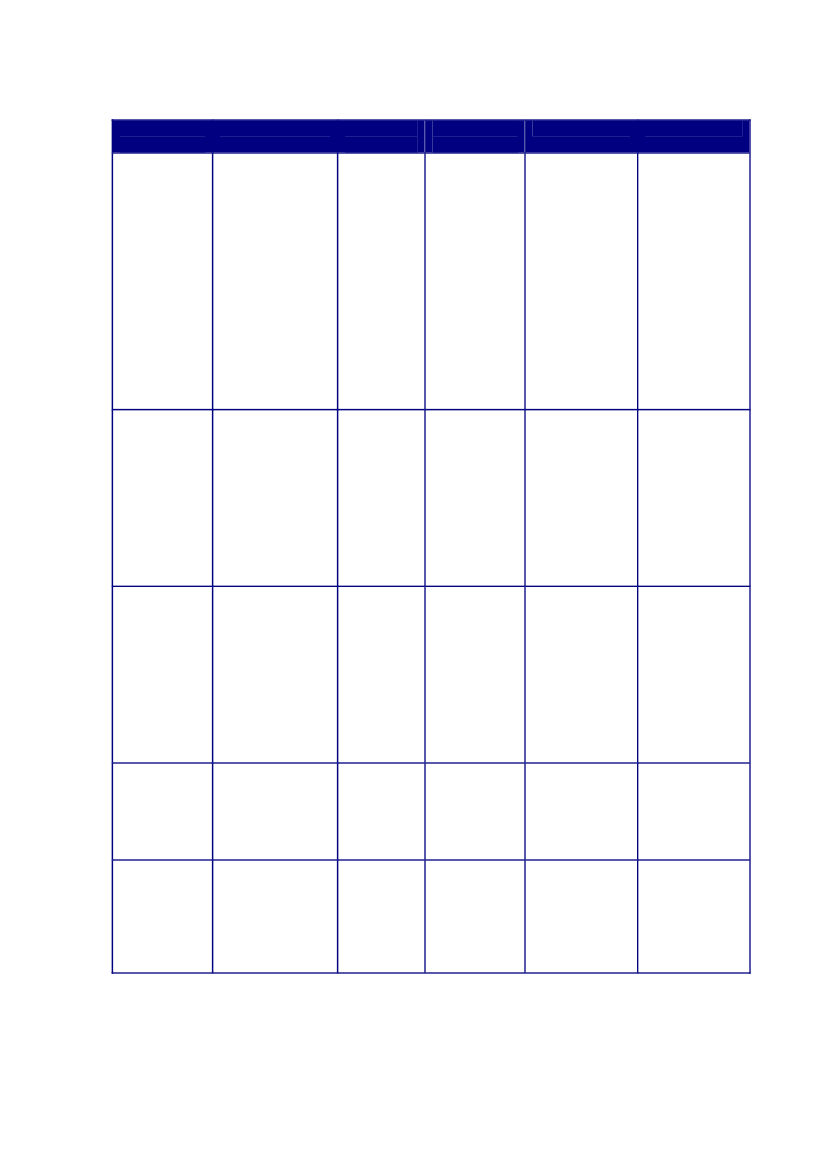

Table of ContentsBackground...........................................................................................................................5Abstract.................................................................................................................................6Chapter 1: Parliamentary control of Europol and evaluation of Eurojust ..............................101.1Current practices in parliamentary scrutiny of Europol and Eurojust ....................101.2Plans for developing parliamentary scrutiny of Europol and evaluation of Eurojust..................................................................................................................................111.3Forms of direct communication between parliaments and National Members ofEurojust and/or Europol Liaison Officers.........................................................................121.4Cooperation with regard to the evaluation of Eurojust and the scrutiny of Europolin the light of the Treaty of Lisbon...................................................................................131.5The role of COSAC with regard to the evaluation of Eurojust and the scrutiny ofEuropol’s activities..........................................................................................................14Chapter 2: The role of the EU parliaments in the promotion of human rights and democracyin the world .........................................................................................................................162.1. Structures established by parliaments to handle the issues of promotion of humanrights and democracy.......................................................................................................162.1.1. Committees dealing with human rights issues ....................................................162.1.2. Debates on the state of human rights and democracy in the world ......................162.1.3. Resolutions and reports on critical human rights and democracy situations in theworld ...........................................................................................................................172.2. Parliamentary control in the field of human rights and democracy ............................172.2.1. Control of the Government.................................................................................172.2.2. Monitoring of the current state of human rights and democracy before concludingan agreement ...............................................................................................................182.2.3. Human rights and democracy clauses in the EC agreements with third countries 192.3. Participation of Parliaments in promoting human rights and democracy....................202.3.1. Projects and initiatives aimed at promoting human rights and democracy...........202.3.2. Criteria applied by parliaments in selecting initiatives and projects promotinghuman rights................................................................................................................22Chapter 3: Representatives of national parliaments to the EU ..............................................233.1. Introduction ..............................................................................................................233.2. Reasons for the decision to send a permanent representative to the EU .....................233.3. Titles of the representatives.......................................................................................243.4. Term in office ...........................................................................................................253.5. Coordination of activities of the representatives of bicameral parliaments.................253.6 Main functions...........................................................................................................263.7 Focus of attention ......................................................................................................273.8 Reporting on developments in the EU and selection of topics ....................................283.9. Administrative accountability ...................................................................................293.10. Reporting on representatives' activities ...................................................................303.11. Attendance of the EU Speakers' Conferences, meetings of the Secretaries Generaland COSAC meetings......................................................................................................303.12. Assistants................................................................................................................313.13. Future developments...............................................................................................31Table 1: History of the Representatives........................................................................32Table 2: Information on the Representatives ................................................................34Chapter 4: Evaluation of the COSAC Bi-annual Reports .....................................................404.1. Picture of the experience of five years of the COSAC Bi-annual Reports..................403

4.1.1. Brief presentation of the first ten Bi-annual Reports (2004-2009).......................404.1.2. Added value of the Bi-annual Reports according to the EU parliaments .............414.2. Prospects for the content of the Bi-annual Reports ....................................................424.2.1. Issue of the link between the content of the Bi-annual Reports and the agenda ofthe COSAC meetings...................................................................................................424.2.2. Selection of topics: experience of the past COSAC Presidencies .......................434.2.3 Proposals for topics for future Bi-annual Reports ................................................444.3. Form of the Bi-annual Reports..................................................................................454.4. Practises of parliaments with regard to the Bi-annual Reports ...................................46

4

BackgroundThis is the Eleventh Bi-annual Report from the COSAC Secretariat.

COSAC Bi-annual ReportsThe XXX COSAC decided that the COSAC Secretariat should producefactual Bi-annual Reports, to be published ahead of each plenaryconference. The purpose of the reports is to give an overview of thedevelopments in procedures and practices in the European Union that arerelevant to parliamentary scrutiny.All the Bi-annual Reports are available on the COSAC website at:http://www.cosac.eu/en/documents/biannual/

The four chapters of this Bi-annual Report are based on information provided by nationalparliaments and the European Parliament.As a general rule, the Report does not specify all parliaments or chambers whose case isrelevant for each point. Rather illustrative examples, introduced in the text as "e.g.", are used.The COSAC Secretariat is grateful to the contributing parliaments for their cooperation.

Note on NumbersOf the 27 Member States of the European Union, 14 have a unicameralparliament and 13 have a bicameral parliament. Due to this mixture ofunicameral and bicameral systems, there are 40 national parliamentarychambers in the 27 Member States of the European Union.Although they have bicameral systems, the national parliaments of Austria,Ireland, Romania and Spain each sent a single set of replies to thequestionnaire drafted by the COSAC Secretariat.The COSAC Secretariat received replies from 40 national parliaments orchambers of 27 Member States and the European Parliament. These repliesare published in a separate annex to this Bi-annual Report which is alsoavailable on the COSAC website at:http://www.cosac.eu/en/documents/biannual/

5

Abstract

CHAPTER 1: Parliamentary control of Europol and evaluation of EurojustCurrently neither national parliaments nor the European Parliament possess sufficient legalmeans to scrutinise directly the activities of Europol and Eurojust. That is whynationalparliaments exercise their control via their governments or findad hocways to beinformed about the activities of Europol and Eurojust.TheEuropean Parliament willasof 1 January 2010,acquire oversight and influenceover the two bodies thanks to theCouncil Decisions agreed in the Justice and Home Affairs Council of 6 April 2009.1There is no systematic scrutiny of Europol and Eurojust at national level, nor is there regularcommunication with the National Member of Eurojust and/or Europol Liaison Officer.However, parliaments widely share the conviction that proper parliamentary control ofEuropol and Eurojust is necessary; the provisions of the Treaty of Lisbon could provide themeans to do so. The Treaty of Lisbon (Art. 88 and Art. 85 of the Treaty on the Functioning ofthe European Union) foresees involving national parliaments and the European Parliament inthe evaluation of Eurojust’s activities, and scrutinising by the European Parliament, togetherwith national parliaments, of Europol’s activities.Parliaments realise the need for changesin their procedures in the light of the possible entry into force of the Treaty of Lisbon,but at this stage are neither specific nor certain about the forms of such changes.There are twoparallel questionswhich parliaments are addressing at present: (i)establishing or upgradingcontrol of Europol and Eurojust on national level,and (ii)establishingscrutiny on inter-parliamentary level.The latter question is specifically linkedto the provisions of the Treaty of Lisbon, which foresee cooperation between the EuropeanParliament and the national parliaments in the scrutiny of Europol and evaluation of Eurojust.Given the initial stage of affairs in these matters, there seems to be aneed for furtherexchange of ideas and best practices.In this respect, specific attention could be paid to thediscussions of theAnnual Reports of Europol/Eurojustin parliaments.When and if the Treaty of Lisbon is ratified it will raise a series of issues. Nationalparliaments request that theEuropean Commission consultswith them before presenting itsproposals for regulations on Europol and Eurojust. Once the proposals are published,theCouncil and the European Parliamentare encouraged in their turn toconsult withnational parliamentsgiving them sufficient time to discuss the proposals amongthemselves. Furthermore, it will be necessary todefine,inter alia,the form, functioning,periodicity, remit, content of work of the mechanisms for evaluating Eurojust andcontroling Europol.The discussion among parliaments on the best platform to implementthese provisions is important and could be debated within COSAC.

1

Council decision establishing the European police office and Council Decision on the strengthening ofEurojust amending Council Decision 2002/187/JHA of 28 February 2002, as amended by Council Decision2003/659/JHA setting up Eurojust with a view to reinforcing the fight against serious crime

6

CHAPTER 2: The role of the EU parliaments in the promotion of human rights anddemocracy in the worldIn most cases, promotion of human rights and democracy in the world are dealt with by theCommittees on Foreign Affairs of EU parliaments.The protection of human rights and democratic standards is a sensitive issue for Members ofParliaments. That is why evaluation of these issues is a regular part of parliamentarydiscussions. The resolutions coming from these debates do not legally bind governments.However, parliaments may, and usually do, pass resolutions or recommendations todrawgovernments’ attention to critical human rights and democracy situationsin thirdcountries.The majority of parliaments are informed about the state of human rights and democracy inthird countries during their debates on international agreements. One of the possible ways tomonitor respect of human rights and democratic principles once the agreement enters intoforce is to include in the agreement a so-called suspension clause conditioning theapplication of the agreement on respecting human rights and democracy. Most parliamentswelcome and support theinsertion of suspension clausesinto agreements between theEuropean Community (henceforth "the EC") and third countries.In general parliaments cooperate with other parliaments, the EU Institutions and internationalorganisations in order to share information on their activities and good practices. They alsocooperate on joint projects, in particular, parliaments tend to cooperate withthe UnitedNations, the Council of Europeandthe Organisation for Security and Cooperation inEurope.CHAPTER 3: Representatives of National Parliaments to the EUSince1991when theDanishFolketingsent the first representative to the EU,there hasbeen a fundamental shift in the approach of national parliaments towards EU matters. Thegrowing number of national parliament representatives in Brussels reflects an increasedinterest in contacts with the EU Institutions, in particular the European Parliament, andcooperation between parliaments. Presently33 representativesof national parliaments orchambersfrom 24 out of the 27 Member States are permanently basedon the premises ofthe European Parliamentin Brussels.The tasks and competences of these representativesvary considerably.National parliaments have abroad spectrum of motivesfor posting permanentrepresentatives in Brussels. Among these are: the need to receive rapid, firsthand informationon the EU developments, to enhance political influence over EU decision-making; and toassist official relationships and direct cooperation between national parliaments and the EUInstitutions and between national parliaments.Representatives carry outmany and diverse functions.However, almost all parliamentsexpect their representatives toreport back on political developments in the EUand toassist Members of Parliament when they attend inter-parliamentary meetings.Thereporting function seems to stay at the top of the representatives' agenda. The time spent oninter-parliamentary cooperation is constantly increasing and, therefore, can divert attention ofrepresentatives from their principal function of reporting back to their parliaments.

7

Networking, exchange of early information and coordination with other representatives inBrussels are considered to beincreasingly important functions,especiallyin view of theenhanced role of national parliaments envisaged in the Treaty of Lisbon.In the vast majority of casespriorities for representatives' workare set in accordance withthe needs of Committees on European Affairs. However, in a number of casesrepresentatives' priorities are shaped by demands of a much broader group of recipients.This chapter also presents an overview of the representatives'terms in office, accountabilityand duty to reportto their nominating parliament.Therole of representativesin Brussels is constantly evolving and a number of nationalparliaments areplanning to reassess it when the Treaty of Lisbon enters into force.Parliaments are considering different ideas, in particular associated with setting upmechanisms for monitoring the implementation of the principle of subsidiarity provided forin Protocol 2 to the Treaty of Lisbon.

CHAPTER 4: Evaluation of the COSAC Bi-annual ReportsOver five yearsCOSAC Bi-annual Reports have become well-established documents,considered by national parliaments to be of a great value. Indeed, thanks to their insight intothe procedures and practices of the EU parliaments, the Reports are appreciated as theyprovideup to date and comparative information, allowing the exchange of best practiceson scrutiny of EU legislation and policy.Since May 2004, the COSAC Secretariat has publishedten Bi-annual Reports.The Reportshavecovered many subjects.The most often covered were subjects related to theConstitutional Treaty, the Treaty of Lisbon, the principles of subsidiarity and proportionalityand scrutiny procedures and practices in national parliaments.Onthe current formof the Reports, there seems to be a consensus among nationalparliaments that it is“accurate” and “satisfactory”.Although some consider that an effortshould be made to make themmore compact and analyticalto improve their impact on thereadership.Parliaments' replies to the questions regarding thecontentof the Bi-annual Reports indicatediverging opinions,especially on the issue of whether there should be a link between thetopics of the Report and the agenda of COSAC Ordinary meetings. Regardless of the natureof the topics, many parliaments are in favour of a link, indicating that the Bi-annual Reportsarea valuable preparatory document for debateson the agenda. Other parliaments drawattention to thenature of the Bi-annual Reports and the COSAC meetings.In theiropinion, Bi-annual Reports are first intended to be procedural reports whilst the COSACmeetings deal with topics of a political nature. Therefore, the rule should be that there is nosuch direct link.The feedback from those national parliaments who have presided over COSAC in the lastfive years, indicates thatthe choice of the subjectsfor the Bi-annual Reports is, above all,based on topicalityto current debates in European Union or in COSAC, and the priorities ofthe EU Presidency.

8

The major issues suggested by parliaments for debate in the coming years are theimplementation of the Treaty of Lisbonwith regard to the enhanced role of the nationalparliaments and, more particularly, the application of the principle of subsidiarity. Thesetopics therefore should continue to be addressed in future Bi-annual Reports. This chapteralso provides a list of various topics suggested by national parliaments.Theproceduresin national parliaments forpreparing and approving repliesto COSACquestionnaires are quite similar. There are, however, a few exceptions. Usually theSecretariats of the Committees on European Affairs are in charge of the replies, often incooperation with other bodies of the parliamentary administration. If the content of thereplies requires, the staff inform the Members, and in a number of cases the replies areapproved by the Chairperson.In a number of parliamentsthe Report is distributed to the Membersof the Committees onEuropean Affairs or to the Members who are attending the COSAC meetings, sometimes toother Members. In a few parliaments there is anopportunity to discussthe content of theBi-annual reports in the Committees on European Affairs.

9

Chapter 1: Parliamentary control of Europol and evaluation of EurojustFrom the moment of their creation, the effective democratic control of Europol and Eurojustand the evaluation of their activities has been a question for national parliaments and theEuropean Parliament alike. They share the notion that current parliamentary control of thesebodies is weak and needs substantial improvement. Against this background they haveengaged in an ongoing inter-parliamentary debate.The Treaty of Lisbon, once ratified and in force, will enhance parliamentary prerogativesboth in the area of Europol (Art. 88 TFEU) and Eurojust (Art. 85 TFEU). The Treatyforesees that national parliaments and the European Parliament shall be involved in theevaluation of Eurojust’s activities and that the European Parliament, together with nationalparliaments, shall scrutinise Europol’s activities. Consequently the issue of defining thiscooperation among national parliaments and between national parliaments and the EuropeanParliament is raised.That is why this chapter firstly takes stock of the current situation of parliamentary scrutinyof Europol and Eurojust by the EU parliaments and secondly looks at the future possibilitiesand necessities of cooperation in this field among national parliaments and between nationalparliaments and the European Parliament.1.1Current practices in parliamentary scrutiny of Europol and Eurojust

Currently there is no legislation setting out procedures for parliamentary scrutiny of Europoland Eurojust. The two EU bodies are accountable to the Council of the EU (Justice andHome Affairs (henceforth “the JHA Council”)). Thusnational parliaments exercise theircontrol via their respective governments.The European Parliament scrutinises theactivities of Europol and Eurojust informally through auditions, hearings and round tablesattended by the Director of Europol and the President of the College of Eurojust.Those national parliaments whose remits are confined to document-based scrutiny acquire acertainad hocoversight over Europol and/or Eurojust when they discuss acts changing thecompetences of the bodies2or agreements of Europol/Eurojust with third countries.Parliaments disposing of the right to hold their governments to account in EU matters usethis right to obtain information regarding Europol/Eurojust at any given moment (the BelgianChambre des Représentants,the FrenchSénat).Some national parliaments entertain relationswith their country’s national representatives in Europol/ Eurojust (see further in chapter 1.3.)and some discuss the reports of Europol annually (the FinnishEduskunta,the DutchTweedeKamer;the LatvianSaeimaand the LithuanianSeimasare starting such procedure) orEurojust (the PortugueseAssembleia da República).Those national parliaments, which have a mandating scrutiny system, discussEuropol/Eurojust if it is on the agenda of a JHA Council meeting.There are two national parliaments which can exercisedirect influence on decisionsrelating to Europol/Eurojust:the IrishHouses of the Oireachtasand the DanishFolketing.2

A recent example:Council decision establishing the European police office(8706/3/08), which has been amatter for ex-ante scrutiny in national parliaments.

10

They have a specific role stemming from to the fact that their respective governments need toseek parliamentary approval prior to agreeing in the Council to their countries' participationin measures under the area of Justice and Home Affairs.Other specific cases are: the FinnishEduskuntascrutinises regularly yet indirectly theactivities of Europol/Eurojust through the government communication on the yearbooks ofthe two institutions. A GermanBundesratrepresentative attends meetings of the EuropolManagement Board and reports on these to the Committee on European Union Questions. Asfor Eurojust, aBundesratrepresentative in the Council Working Group on cooperation inCriminal Matters reports to the Committee on European Union Questions. The ItalianParliament’s joint committee is charged with scrutinising the implementation of the EuropolConvention.When envisaging future developments and possibilities of inter-parliamentary cooperation, itis important to note the obvious: national parliaments currently scrutinise Europol/Eurojustwithin their system of general scrutiny of Justice and Home Affairs. This involves in somecases the Committees on EU Affairs, in other cases the specialised committees or acombination of both.1.2 Plans for developing parliamentary scrutiny of Europol and evaluation ofEurojustThe latest developments in this field are in relation to the European Parliament (henceforth"the EP"). TheEP will acquire oversight powersas defined in the Council Decisionestablishing the European police office3and Council Decision on the strengthening ofEurojust amending Council Decision 2002/187/JHA of 28 February 2002, as amended byCouncil Decision 2003/659/JHA setting up Eurojust with a view to reinforcing the fightagainst serious crime4. Both Decisions were approved by the JHA Council on 6 April 2009and will enter into force as of 1 January 2010. The EP will,inter alia,adopt the budgets ofEuropol and Eurojust and will have the right to be informed of their activitiesonrequest.National parliaments envisage new developmentsin parliamentary scrutiny of Europol andEurojustalmost exclusively in connection to the Treaty of Lisbon(see chapter 1.4.). Mostnational parliamentsdo not have ready-made scenariosfor the scrutiny following possibleentry into force of the Treaty of Lisbon. This is partly due to the still ongoing ratificationprocess and uncertainty over its end result.Some parliaments (e.g. the BelgianChambre des Représentants,the EstonianRiigikogu,theRomanianCamara Deputatilor,the HungarianOrszággyüllés)already define the modalitiesof their future involvement,i.e.establishing a specific administrative task force, evaluatingthe current scrutiny system, holding sittings of relevant committees together with governmentrepresentatives and the national representatives in Europol/Eurojust. In general, manyparliaments claim to be envisaging new modes of control without further detailedspecification. In this respect it is recommended to consult the results of the inquiry carried

34

8706/3/0814927/08

11

out by both Houses of the UK Parliament5, which provide a concise analysis of the currentsituation and outline a framework for possible future arrangements including questions to beconsidered.1.3 Forms of direct communication between parliaments and National Members ofEurojust and/or Europol Liaison OfficersUnsurprisingly the extent to which parliaments in the European Union have established directcommunication with the respective National Member of Eurojust and/or Europol LiaisonOfficer varies greatly in form, regularity, intensity and quality. In many casescommunication is scarce,if established at all.Where communication is established it is mainlyad hoc, i.e.it is established wheneverdeemed necessary (e.g. the EstonianRigikogu,the GermanBundestagwith its relevantcommittees, the FrenchSénat,the PolishSejm).Among other possibilities thead hoccommunication can take the form of hearings or expert meetings (e.g. the HungarianOrszággyülésor the FinnishEduskunta).Some parliaments had visits to the seats ofEuropol/Eurojust.In a number of parliaments communication with Europol/Eurojust is rather indirect,established through the national government, which is politically accountableto theparliament for these two executive bodies (e.g. the BelgianSénatandChambre desReprésentants,the AustrianNationalratandBundesrat).In some national parliamentsMembers,e.g.of their specialised committees, might contact their respective NationalMembers of Eurojust or Europol Liaison Officers on their own initiative, usually forparticular inquiries.However, a few parliaments have been able to developmore regular and extensivecontacts.In the case of the PortugueseAssembleia da República,since 2007 its Committeeon Constitutional Affairs, Rights, Freedoms and Guarantees has been assessing the annualreports of Eurojust. As of 2008, this committee has also organised jointly with the Committeeon EU Affairs meetings with Mr José Luís Lopes da MOTA, the Portuguese NationalMember of Eurojust and the current President of the College of Eurojust, on the activities ofEurojust and on the European Space of Freedom, Security and Justice.The European Parliament has developed a line of direct communication with bothorganisations. The heads of both Europol and Eurojust have been invited to attend committeemeetings or hearings. They also present reports recently adopted by their organisations to theCommittee on Civil Liberties, Justice and Home Affairs, such as the Annual Report ofEurojust or the EU Terrorism Situation and Trend Report (TE-SAT) of Europol. In addition,the organisations have been visited by Members’ delegations and contacts at administrativelevel have been established.

5

See chapter 5 of the House of Commons’s report:Subsidiarity, National Parliaments and the Lisbon Treaty(33rd Report of 2007-08, HC 563) and the House of Lords report:EUROPOL: coordinating the fight againstserious and organised crime(29th Report, Session 2007-08, HL Paper 183, published 12 November 2008).

12

1.4 Cooperation with regard to the evaluation of Eurojust and the scrutiny of Europolin the light of the Treaty of LisbonThe Treaty of Lisbon6foresees that national parliaments and the European Parliament shallbe involved in the evaluation of Eurojust's activities and that the European Parliamenttogether with national parliaments shall scrutinize Europol's activities.In its consolidated version the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (henceforth“the TFEU”) stipulates that on the basis of a proposal by the European Commission and inthe framework of the ordinary legislative procedure the European Parliament and the Councilshall adopt a regulation which,inter alia,shall “determine arrangements for involving theEuropean Parliament and national parliaments in theevaluation of Eurojust’s activities”(Article 85 TFEU) and “lay down the procedures forscrutiny of Europol’s activitiesby theEuropean Parliament, together with national parliaments” (Article 88 TFEU).The answer to the question on how national parliaments could cooperate together and withthe European Parliament in this area is determined by the fact that the ratification of theTreaty of Lisbon is still pending. It is therefore unsurprising that many parliamentshave putthis question aside for the moment(e.g. the AustrianNationalrat and Bundesrat,theBelgiumSénat,the DanishFolketing,the GermanBundestag),intending to raise it againonce the ratification is completed. Others are currently examining the implications of theprovisions for their parliaments.Nevertheless, many of the answers to the questionnaire, on which this report is based, revealideas and suggestions or – equally important – points of substantial concerns and potentialdifficulties, which should be addressed in the framework of any future solution.With a view to the elaboration and adoption of the regulations envisaged in Articles 85 and88 of the TFEU, a number of national parliaments made it clear that theyexpect to beconsulted by the involved EU Institutionsabout the drafts of the regulations and during theprocess of their adoption. According to the UKHouse of Commons,reasonable time shouldbe given to national parliaments in which to consult each other in COSAC and preparecomments. Equally, theHouse of Commonshas raised a number of questions which are ofrelevance to all parliaments,e.g.concerning potential constitutional implications of theregulations, the purpose of the evaluation or scrutiny and its follow-up or the matters ofpracticality and organisation.Regarding the actualform of cooperationin these areas, a number of suggestions have beenmade. They range from theuse of existing inter-parliamentary meetings(e.g. the FinnishEduskunta),the creation of a specificmixed committee composed of Members of nationalparliaments and the European Parliament(e.g. the FrenchSénat)toenhancing the roleof COSAC(see further in chapter 1.5.) or the combination of all above.Currentlymost of the specific proposals build on already existing forms of cooperation.In this context, a considerable number (e.g. the BelgianChambre des Représentants,theFinnishEduskunta,the FrenchAssemblée nationale,the GreekVouli Ton Ellinon,the IrishHouses of the Oireachtais,the LatvianSaeima, the Slovenian Državni svet)of parliaments6

See Art. 85 TFEU (ex-Art. 31 TEU) and 88 TFEU (ex-Art. 30 TEU), Official Journal of the European Union,C 115/81 from 09.05.2008.

13

have mentioned that eitherJoint Committee Meetings (JCM) or Joint ParliamentaryMeetings (JPM)could be considered as possible instruments to achieve an efficientcooperation among parliaments. This position is also explained by the intention to avoid yetanother new form of inter-parliamentary cooperation. In this context, it appears that a numberof national parliaments (i.e. the FrenchAssemblée nationale,the LithuanianSeimas,the UKHouse of Lords)are looking to the European Parliament to put forward ideas on the specificforms of cooperation with national parliaments, including using already existing fora.Whatever the form of inter-parliamentary cooperation, in general parliaments agree thatmeetings should have aclearly defined periodicity.The most frequent suggestion was tomeet at leastonce a yearto discuss matters of Europol and Eurojust.The European Parliament in its resolution of 25 September 2009 considered that apermanent monitoring mechanismshould be built up, associating the European Parliamentand national parliaments not only as far as Europol and Eurojust activities are concerned, butalso with regard to issues related to Schengen, migration and asylum. Moreover, theCommittee for Civil Liberties, Justice and Home Affairs has proposed to maintain thepractice of an annual debate with national parliaments on issues related to the Area ofFreedom, Security and Justice, which should be prepared by previous consultations withnational parliaments and should be accompanied by the direct involvement of nationalparliaments’rapporteurson specific legislative proposals.In addition to specific forms of cooperation, where Members of national parliaments and theEuropean Parliament meet directly, a considerable number of parliaments stressed theimportance of intensifying the exchange of information in this area. Many parliamentsmentioned that IPEX could be instrumental in this context, provided that information isaccessible to all parliaments7. Furthermore the IrishHouses of the Oireachtassuggested thatthe European Parliament and its responsible committees “should be encouraged tosystematically share” relevant reports with national parliaments.The EU Speakers’ Conference in June 2008 in Lisbon encouraged national parliaments toalso post on the IPEX website summaries in English or French and other languages ofimportant decisions, as well as the relevant internal scrutiny procedures, which werefollowed.1.5 The role of COSAC with regard to the evaluation of Eurojust and the scrutiny ofEuropol’s activitiesThere is aconsiderable diversity of viewson the potential role which COSAC could play inrelation to the future evaluation of Eurojust and the scrutiny of Europol activities. It exposesvarying understanding among parliaments about the general character of COSAC and thescope and intensity of its activities as well as it reflecting the current difficulties for dealingwith Eurojust and Europol matters.

7

The accessibility of information is directly linked to the availability of scrutiny information from nationalparliaments in more than one language. The EU Speakers at their meeting on 20-21 June 2008 in Lisbonencouraged "national parliaments to include summaries in English or French and other languages of importantdecisions and in relation with the relevant internal scrutiny procedures which were followed". This request ofthe Speakers is currently far from being implemented and poses considerable limitations to the accessibility ofinformation on IPEX.

14

A number of parliaments (e.g. the AustrianNationalratandBundesrat,the CzechPoslanecká Sněmovna,the CypriotVouli Antiprosopon,the GermanBundesrat,the PolishSejm,the DutchEersteandTweede Kamer,the HungarianOrszággyülés,the LuxembourgishChambre des Députés)stated thatCOSAC could serve as a forumfor discussing, sharingideas and exchanging information as well as the best practices related to both issues.According to the CypriotVouli Antiprosopon,meetings of COSAC could focus onformulation of guidelines, recommendations and common standards on how to performthe parliamentary scrutinyof the two organisations´ activities.Some parliaments expressed the opinion that such debates (including the analysis of annualreports of Europol and Eurojust) should take placeonce a yearin COSAC (e.g. the DanishFolketing,the IrishHouses of the Oireachtais,the LithuanianSeimas,the LatvianSaeima).Others (e.g. the CzechSenátand the CypriotVouli Antiprosopon)suggested in addition thatthe Director of Europol as well as the President of the College of Eurojust should be invitedto participate in these deliberations to provide information on the activities of their respectiveorganisations during the current year and those planned for the following year. According tothe BulgarianNarodno Sabraniethe heads of both organisations should be invited toCOSAC hearings every two years.Furthermore, some parliaments considered thatevaluation of Eurojust and the scrutiny ofEuropol’s activities should be a regular point on the agenda of COSAC meetings(e.g.both chambers of the Italian Parliament, the FrenchAssemblé Nationale,the LuxemburgChambre des Députés,the EstonianRiigikogu,the SlovakianNárodná Rada).According tothe BelgianChambre des ReprésentantsCOSAC meetings could also play an alertingfunction of drawing attention to possibly problematic aspects of activities of Europol andEurojust. In addition the FrenchSénatrecalled that the Treaty of Lisbon, in Protocol 1 on theRole of national Parliaments in the European Union, foresees the possibility that COSAC“may also organise interparliamentary conferences on specific topics”.Notwithstanding the above, some parliaments revealeddoubts over a role for COSAC inthe evaluation of Eurojust and the control of Europol activities(e.g. the BelgianSénat,the FinnishEduskunta,the GreekVouli Ton Ellinon).Some of the concerns are linked to thepotential impact on COSAC’s current agenda and organisationand the suitability ofCOSAC to deal with items which are actually amatter for specialised committees(e.g.FrenchAssemblée Nationale).In the same sense theEuropean Parliamentbelieves thatscrutiny and evaluation of Europol/Eurojust should rather be left to the competent specialisedcommittees. Eurojust and Europol's activities in the European Parliament’s view should bediscussed within COSACwhenever a substantial debate is possible and necessarywithoutpre-empting the scrutiny and evaluationof the activities of the two organisations by eachindividual parliament.

15

Chapter 2: The role of the EU parliaments in the promotion of humanrights and democracy in the worldWhether in the EU or in the world parliaments are important guardians and promoters ofhuman rights and democracy standards. Since the EU is a system of reference for manycountries, its role as the guardian and promoter of human rights has been strengthened.This chapter firstly presents an overview of the structures and systems, established and usedin EU parliaments for handling promotion of human rights and democracy; and, secondly,highlights examples of best practices, instruments and selection criteria used to promotehuman rights and democracy in the world.Article 6/1 of the TEU states that:"The Union is founded on the principles of liberty, democracy, respect for human rights andfundamental freedoms, and the rule of law, principles which are common to the MemberStates."2.1. Structures established by parliaments to handle the issues of promotion of humanrights and democracy2.1.1. Committees dealing with human rights issuesIn the majority of parliaments human rights are dealt with by more than one committee,depending on the specific issue. Thus, Committees on Constitutional Affairs (in 9 cases),Committees on Legal Affairs (in 8 cases) and/or Committees on Justice Affairs (in 5 cases),are mostly competent for domestic human rights questions, whereas Committees on ForeignAffairs (in 23 cases) mostly deal with the international aspect of the issue. Some parliamentshave establishedspecialised Committees on Human Rights(in 17 cases) orspecialisedsub-committees on Human Rights(in 3 cases, all of them created under Committees onForeign Affairs). Committees on EU Affairs (in 7 cases), Committees on Equal Opportunities(in 2 cases), or Delegations for Parliamentary Cooperation (in 3 cases), were also mentionedby parliaments.The role of these committees in the framework of human rights matters is usually exercisedthrough organisation of debates and/or publication of reports (see below 2.1.2 and 2.1.3).2.1.2. Debates on the state of human rights and democracy in the worldMost parliaments report having debates on the actual state of human rights and democracy inthe world, eitherregularly(in 16 cases) or on anad hocbasis (in 17 cases).Among the replies, theEU Annual Report on Human Rights8appeared four times as abasis of the parliamentary discussion (in the European Parliament, the ItalianCamera dei8

http://ue.eu.int/showPage.aspx?id=970&lang=en

16

Deputatiand theSenato della Repubblicaand the GermanBundestag)and thereports onthe activities of the Council of Europewere quoted three times (in the GermanBundesrat,the PortugueseAssembleia de Repúblicaand the DutchTweede Kamer).The CzechSenátand the DutchTweede Kameralso mentioned a discussion taking place before the GeneralAffairs and External Relations Council (GAERC).In the FinnishEduskuntahuman right issues are considered to be cross cutting. That is whythese questions as well as questions concerning the democracy in the world are oftendiscussed in the framework of the overall discussions, mostly on the ratification ofmultilateral or bilateral agreements.Debatesare held either in plenary sessions (e.g. the European Parliament or the EstonianRiigikogu)or,more often, within the relevant committees.The frequency of debatesmostly depends on current international events (e.g. the situation in on the Eastern Balkans,in Belarus, Georgia, Gaza, Tibet, etc.) and/or the will of the parliaments.2.1.3. Resolutions and reports on critical human rights and democracy situations in theworldNo example of legally binding a government by resolutions passed by a parliament in thisfield was given. However, parliaments may pass and usually do pass resolutions orrecommendations todraw the government’s attention to critical human rights anddemocracy situationsand maytake positionstowards the states where human rights anddemocracy are endangered. For example, the PortugueseAssembleia de República,theLithuanianSeimas,both Chambers of the Italian Parliament or the CzechSenátgave anumber of examples of such resolutions.As far as the publication of reports is concerned only a few examples were given. TheEuropean Parliament publishes its Annual Report on Human Rights in the World9, while theForeign Affairs Committee of the UKHouse of Commonspublishes an annual report onhuman rights issues, to which the Government is obliged to respond.The Foreign AffairsCommittee of the SwedishRiksdagannually presents committee reports on the subject ofhuman rights and democracy in the world where the recommendations to the Governmentcan be included.In addition to parliamentary reports, reports issued outside parliaments are also basis fordiscussions. Such reports are published mostly by the governments (e.g. the FinnishGovernment presents to theEduskuntaonce in its term a White Paper on Human RightIssues, the SlovakianNárodná radadiscusses the Government’s report on the foreign policyof the previous year and the report on the priorities for the next year, including the humanrights issues or the CzechPoslanecká sněmovnareports that the Government is responsiblefor presenting an annual report on the human rights and democracy to the Committee onPetitions) or other international organisation (see 2.1.2.).2.2. Parliamentary control in the field of human rights and democracy2.2.1. Control of the Government

9

http://www.europarl.europa.eu/comparl/afet/droi/annual_reports.htm

17

Following the principle ofseparation of powersthe government negotiates and concludesinternational agreements and theparliament exercises its control.To make this controleffective parliaments have established structures and procedures in accordance with theirconstitution.Most parliaments do not have any special procedures for controlling government on humanrights and democracy, but they can use all the available instruments under their rules ofprocedure: such as oral and written questions, hearings with ministers,ad hocdebates,requests for information, etc. These measures can be used as a source of information for theparliament and they enable a closer exchange of views with the government that is inprinciple accountable to the parliament. The weight of these measures naturally rises in caseswhere a parliamentary ratification procedure is foreseen.The institutionalised and continuous communication between the government and theparliament (e.g. the GermanBundestag'sCommittee on Human Rights and HumanitarianAid, is not a legislative committee but it is in continuous contact with the Government andexercises its parliamentary control by, for example, inviting members of the Governmentregularly to its sittings), close control of financing (e.g. the UKHouse of Commonsdecidesthe overall funding for the Foreign and Commonwealth Office and the Department forInternational Development) orad hocinquiries (e.g. the Committees dealing with HumanRights within the RomanianCamera Deputaţilorandthe Senatulmay initiate aparliamentary inquiry regarding any ministry activity or other public authority) could be seenas measures to a more effective control of governments.The BelgianChambre des Représentantsdrew attention to the possibility of controlling thepolicy of its governmentvia broader parliamentary platformssuch as the ParliamentaryAssembly of the Council of Europe, the Parliamentary Assembly of the Organisation forSecurity and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE) or the Euro-Mediterranean ParliamentaryAssembly (EMPA).2.2.2. Monitoring of the current state of human rights and democracy beforeconcluding an agreementThe evaluation of human rights and democracy standards is regularly a part of overallparliamentary discussion before concluding an agreement with a third country as these topicsare sensitive for Members of Parliament. Therefore the governments can anticipate theirinterest and submit this information together with a background paper or an explanatorymemorandum on the bill of ratification. This is often the way parliaments get thisinformation even if governments are not under an explicit obligation to do so. An exceptionis, for example, the Belgian Government which has a special obligation to submit to theChambre des Représentantsa report on the state of human rights in the case of 18 countrieswith which Belgium has direct bilateral cooperation (development aid).If the information is not available this way there are still regular procedures of theparliamentary control of government that can be used in order to get the information needed(see above 2.2.1.).Because the government is expected to know the situation in the given country best, it isnaturally the principal source of information. Nevertheless, parliaments are susceptible to anyother information.

18

Such additional sources of information are, for example, parliamentary debates on humanrights and democracy (see 2.1.2.), reports published or discussed within the parliament (see2.1.3.), fact-finding missions (e.g. the FrenchSénatcan initiate a fact-finding mission thatserves as a bases for a background document), visits or preliminary assessment of specialisedcommittees on a request of the lead committee (e.g. the ItalianSenato della Repubblicastatesthat before an agreement with a third country is ratified its Committee on Human Rights iscalled to give an opinion; also, the Joint Committee on Human Rights of the UKHouse ofCommonsand theHouse of Lordsreports on the human rights implications of everygovernment bill passing through the Parliament).2.2.3. Human rights and democracy clauses in the EC agreements with third countriesMany EU parliaments consider respect for human rights standards or at least willingness toimprove in this respect in the third countries to be a prerequisite for further cooperation withthese countries.One of the possible ways to influence respect of human rights and democratic principles oncean agreement enters into force is to include asuspension clause on human rights anddemocracy,conditioning the application of the agreement on respect of human rights in thecountry in question. Such suspension clauses may be activated whenever their provisions arebreached. So, when the clause is breached the agreement could be suspended or eventerminated.The so-calledhuman rights and democracy suspension clauses on human rights anddemocracycould be an effective instrument of promoting the respect of human rights anddemocracy. Initially these clauses were seen as a non-binding declaration rather then aneffective instrument. That is why progress was made by gradual reformulation of theseclauses.The suspension clauses conditioning the application of agreements between the EC and thirdcountries by respecting the human rights are being used since the Lomé Convention withACP countries10and have becamestandard parts of agreements between the EC andthird countries.The specificity of this approach consists in the importance accorded tosocial and political considerations, for example, byencouraging democratisation andrespect for human rights.The human rights and democracy clauses are, in compliance with Art. 177/2 and 181a TEC11,progressively incorporated into the EC association, business or partnership agreements.10

The ACP countries (Group of African, Caribbean and Pacific countries) are the countries that are signatoriesof the Lomé Convention with the European Commission. The first Lomé Convention was signed in Lomé(Togo) in 1975.11Article 177"2. Community policy in this area shall contribute to the general objective of developing and consolidatingdemocracy and the rule of law, and to that of respecting human rights and fundamental freedoms."Article 181a"2. Without prejudice to the other provisions of this Treaty, and in particular those of Title XX, the Communityshall carry out, within its spheres of competence, economic, financial and technical cooperation measures withthird countries. Such measures shall be complementary to those carried out by the Member States andconsistent with the development policy of the Community.

19

The majority of parliaments explicitly welcome and support the insertion of the human rightsand democracy clauses into the agreements between the EC and third countries. The ItalianCamera dei Deputatiand theSenato della Repubblicaindicates a tendency of inserting thesuspension clauses in their own international agreements. On the other hand, the FrenchAssemblée nationalesupports the clause in principle, but states that the implementation ofthese clauses is far from being ideal. The DutchEerste Kamersupports the suspensionclauses too but thinks that the EU should use more the knowledge, experiences andinstruments of the Council of Europe regarding human rights, democracy and the rule of law.There is no parliament with a negative position on the use of the suspension clauses. On theother hand, some parliaments (in 12 cases) declare that they have not discussed this specificissue or that they do not have any formal position on it yet.2.3. Participation of Parliaments in promoting human rights and democracyIt is not only the EU Institutions and the governments of the EU Member States that have arole in projects aimed at promoting human rights and democracy. The outcome of theStrategy Paper 2007-2010 on European Instrument for Democracy and Human Rights(EIDHR)12, for example, underlines that there is general acceptance of the need for the so-called“local ownership” of the development and democratisation processthat shouldengage public institutions of the relevant third countries. It would be difficult to achieve it ifrelations with partner countries remained limited to government-to-government contacts.2.3.1. Projects and initiatives aimed at promoting human rights and democracyDiscussions, hearings, conferences on human rights and democracy are the means that areoften used by parliaments to promote human rights and democracy. Other possible forms arestudy visits or seminars for the representatives of EU parliaments and/or those from the thirdcountries which provide more interaction among the participants.A majority of parliaments express their support for projects aimed at promoting human rightsand democracy in the third countries. Even if some parliaments do not have any suchexperience yet, they refer to the individual initiatives of their Members. The activities ofparliaments in this area are naturally influenced by their geographic preferences13and differwith regards to type of activity or partners they cooperate with.A few interesting examples of the projects and initiatives are: the GermanBundestag'sinitiative called “Parliamentarians protect Parliamentarians”14; the CzechSenát'screation ofits new Standing Commission on Assistance to Worldwide Democracy aimed at directsupport of democracy outside the EU; the ItalianCamera dei Deputati's“a Centre for thetraining of the parliamentarians of the South-Eastern Europe” that was launched by thePresident of theCamera dei Deputati,the President of the Albanian Assembly and theChancellor of the Tirana’s University; the DanishFolketing'sstanding agreement with itsCommunity policy in this area shall contribute to the general objective of developing and consolidatingdemocracy and the rule of law, and to the objective of respecting human rights and fundamental freedoms."12http://ec.europa.eu/europeaid/where/worldwide/eidhr/documents/eidhr-strategy-paper-2007_en.pdf13E.g.through its Overseas Office the UKHouse of Lordsand theHouse of Commonscontribute to a range ofprogrammes and initiatives throughout the world, with a strong focus on Commonwealth countries.14http://www.bundestag.de/htdocs_e/committees/a17/flyer.pdf

20

Ministry of Foreign Affairs on providing parliamentary assistance to new and emergingdemocracies; the FinishEduskunta'sspecial human rights group that acts very actively inbridging the activities of theEduskuntaand the Council of Europe as well as the UnitedNations; and the GreekVouli ton Ellinon'sInstitution for the Democracy andParliamentarism, whose main objective is to promote the values of parliamentary democracy,by organising conferences, exhibitions, publishing books.For more concrete examples please look at the annex to this rapport with the replies ofparliaments. The parliaments had also the possibility to present their projects and initiativesvia theIPEX surveythat is available on its website15.2.3.1.1. Cooperation with the Council of EuropeA number of parliaments have emphasised their cooperation with the Council of Europe16(henceforth "the CoE") (in 14 cases) referring to the initiatives and projects connected to theactivities of the CoE. The reason for that is, firstly, the membership of all the EU MemberStates in the CoE with its geographic coverage of the nearest region, and, secondly, the CoE,which advocates protection of human rights, pluralist democracy, rule of law anddevelopment of the principles of democracy based on the European Convention on HumanRights. More specifically, the active participation in the Campaign of the CoE to CombatViolence against Women17was mentioned repeatedly in the answers of parliaments. TheForum of the CoE on the Future of Democracy18was also mentioned (the PolishSejm).To reconfirm the enhancement of the cooperation within the CoE to promote human rightsand democracy, the delegation of the DutchEerste Kamer,for example, proposed to use theoccasion of the anniversary of the 60th anniversary of the CoE19and the 50th anniversary ofthe European Court of Human Rights in Strasbourg20. In addition, the GermanBundesrathasalready repeatedly argued that improvements are needed to ensure that the work of theEuropean Court of Human Rights is more efficient.2.3.1.2. Inter-parliamentary cooperation and cooperation with other organisationsFirst of all, undoubtedly the EU plays an important role in the area because of itscoordination role, its investments into information campaigns and support to the inter-parliamentary cooperation.Besides, within the inter-parliamentary cooperation, the EU Speakers’ Conference haslaunched a project on the assistance to Parliaments of new and emerging democracies aimedat promoting cooperation among the EU parliaments and the EU Institutions, notably theEuropean Commission21.

15

http://www.ipex.eu/ipex/webdav/site/myjahiasite/groups/CentralSupport/public/NEDs/survey_latestversion_3_3_09.pdf16http://www.coe.int/T/e/Com/about_coe/17http://www.coe.int/t/dg2/equality/domesticviolencecampaign/Closingconference_en.asp18http://www.coe.int/T/E/Integrated_Projects/Democracy/19The Council of Europe was established on5 May 1949by Treaty of London.20The European Court of Human Rights was established by the Council in Strasbourg on18 September 1959.21Cf. Conclusions of the Conference of the Speakers of the EU Parliaments, Bratislava, 27 May 2007:http://www.eu-speakers.org/upload/application/pdf/c92ab674/EUSC%20Conclusions%2026.5.07.pdf

21

Some parliaments also invest in institutionalisation of that cooperation (e.g. the GreekVouliton Ellnionset up an Institution for Democracy and Parliamentarism in order to promote thevalues of parliamentary democracy and the LithuanianSeimasestablished the Centre forParliamentary Cooperation in order to share the Lithuanian experience of the EU integrationand democratic reforms to the staff and Members of Parliaments of the countries aspiring todemocratic reforms).Some national parliaments also underlined their participation in programmes arranged,e.g.by the United Nations22, the Organisation for Security and Cooperation in Europe23or theInter-Parliamentary Union24. Some parliaments also reported that they or their Memberscooperate with relevant non-governmental organisations or other institutions depending inprinciple on their preferences, either geographical25or concerning the activity26.In cooperation with these organisations many parliaments also participate, either regularly oron anad hocbasis, inelection observation missionsin third countries. Apart from theactivities and the cooperation within the parliamentary assemblies of several internationalorganisations, there are the so-calledfriendship groupsestablished in parliaments in orderto create parliamentary fora aimed at promoting international relations. The friendshipgroups, which fit into the concept of parliamentary diplomacy, enable Members ofParliament to share information of mutual interest.2.3.2. Criteria applied by parliaments in selecting initiatives and projects promotinghuman rightsNaturally, the procedures and criteria for selecting the initiatives and projects aimed atpromoting human rights and democracy differ from one parliament to another. Some criteriacould be deduced from the answers given, such as effectiveness, impact on democracy andhuman rights standards, as well as the regional orientation depending on the externalpriorities. On the other hand, most of the parliaments either have not set formal criteria orwere not able to provide specific information. The enumerated criteria, however, indicate thetendency of certain flexible application to satisfy actual needs.

22

E.g.,the UNDP (UN Development Programme) currently supports one in every three parliaments in theworld in order to seek a “solid parliamentary institutions that are critical to the establishment and consolidationof democracy since they empower ordinary people to participate in the policies that shape their lives“.http://www.undp.org/publications/annualreport2008/downloads.shtmlThe ItalianCamera dei Deputatimentioned its partnership with the United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs (UNDESA) withthe denomination “Strengthening Parliaments’ Information Systems in Africa”, targeted at some Africancountries (www.ictparliament.org).23http://www.osce.org/activities/24http://www.ipu.org/english/home.htm25The Eastern Balkans, Ukraine or Moldavia was mentioned most often.26E.g.,the ItalianSenato della Repubblicainvolves itself fully into the support of programmes against theDeath Penalty and there where the execution of this penalty is likely, the Senators intervene even actively inplace.

22

Chapter 3: Representatives of national parliaments to the EUPresently national parliaments of 24 out of the 27 Member States have one or more officialsbased permanently in Brussels. Their tasks and competences vary considerably.This chapter aims to examine the expectations national parliaments have of theirrepresentatives (focusing on the content of their work and their role) and their future plans inthis regard.The chapter also presents an overview of the broad-ranging practices of national parliamentsin appointing their representatives in Brussels. The chapter compares the practices of therepresentatives' term in office, main functions, accountability, duty to report to thenominating parliament, relations with the Member State's Permanent Representation to theEU, and other related aspects. The chapter also looks at the specific reasons behind thedifferent practices of national parliaments.Based on the information supplied by national parliaments, this chapter attempts to give anoverview of the best practices and procedures of national parliaments in this area.3.1. IntroductionIn 1991, the official ofthe DanishFolketingMr Peter Juul LARSENbecamethe firstnational parliament representative to the EUin Brussels. In 1995, the FinnishEduskuntawas the second to send a representative to Brussels, in 1998 - the ItalianCamera deiDeputati,in 1999 – the FrenchSénat,and the United KingdomHouse of Commons.Since themid 1990s, the representatives have been hosted by the European Parliament. With theenlargements of the EU in 2004 and 2007 the number of national parliament representativesto the EU soared.Presently, national parliamentsof 24 out of 27 Member States have one or more officialspermanently basedin the European Parliamentin Brussels27. Five bicameral parliaments:the Belgian, the Czech, the French, the Polish and the UK, have two representatives,representing each of their chambers, three bicameral parliaments: the Austrian, the Irish andthe Dutch, designated only one representative, while in three other cases of bicameralparliaments only their lower chambers have representatives. These are the GermanBundestag,the RomanianCamera Deputatilorand the SlovenianDržavni zbor.The ItalianCamera dei Deputatihas 5 officials performing the function of the representative. Theyalternate on a weekly basis. Thus, currently,33 national parliaments or chambers out of40have the total of33 representativesin Brussels. The rapid growth of the number ofnational parliaments’ representatives to the EU illustrates the increased attention of nationalparliaments to EU matters.3.2. Reasons for the decision to send a permanent representative to the EUNational parliaments quote a number of reasons for their decision to send theirrepresentatives to Brussels. For instance, in 1995 the main reason for the FinnishEduskunta27

Currently, the Maltese Parliament, the Slovakian Parliament, the Spanish Parliament as well as the GermanBundsrat,the RomanianSenatuland the SlovenianDržavni svetdo not have representatives in Brussels.

23

was a recurrent problem of access to EU documents. Subsequently, the reporting function oftheEduskuntarepresentative and the general political significance of the parliamentaryrepresentative's physical presence in Brussels were the main justifications for continuing thepost.In 1998 the UKHouse of Commonssaw "great potential value" in the establishment of anOffice in Brussels, which in its opinion "should not simply be a post-box nor again just aglorified protocol office. It is in no way a replication of UKREP28: its prime purpose must beto act as a forward observation post for the House, and to act as the eyes and ears of theEuropean Legislation Committee acting on the House's behalf."29In 1999, the FrenchSénatdecided to create a permanent administrative office in Brussels soas to get access to "a rapid and complete information at all stages about issues discussed inBrussels" and "to be able to intervene "upstream" into the EU decision-making process sothat the position of the FrenchSénatcan be expressed as soon as possible, before thedecision-making process is completely set in motion" as well as "to alert the authorities ofthe EU about the concerns of the French citizens".Amongthe objectivesfor posting a permanent representative in Brussels nationalparliaments singled out the following:to follow and report backat an early stageon the EU decision-making processandother developments in Brussels in order to enhance democratic control and politicalinfluence on the EU decision making process;to provide rapid,diversified andup-to-date informationon EU matters, thusfacilitating the work of national parliaments on EU issues with special regard to thescrutiny procedure;to communicateinformation about national parliaments' dealingswith EU issues;to assist inpreparing for the EU Presidency,especially in view of the membershipin the COSAC Secretariat during 18 months;to assist official relationships anddirect cooperationbetween national parliamentsand theEU Institutions,including the European Parliament;to organisevisits of Members of Parliamentand parliamentary officials to the EUInstitutions and to provide additional support for those participating in inter-parliamentary events;to develop working relations between national parliaments throughnetworking andexchanging of informationthrough their permanent representatives in Brussels,especially in view of the enhanced role of national parliaments envisaged in theTreaty of Lisbon;to provide a valuablepart of career developmentfor parliamentary officials.3.3. Titles of the representativesTitlesof the national parliaments' representatives in Brusselsvary considerably.The titlescan be divided into three groups in accordance to the attribution of the representatives to theEuropean Union, to the European Union Institutions or to the European Parliament.

2829

The Permanent Representation of the United Kingdom to the EU.HC 791, 1997-1998, Para 42.

24

The largest part of the parliaments and chambers (13 out of 33) chose the title "The(Permanent) Representative/Officerto the European Union"30, seven parliaments orchambers chose the title "(Permanent) Representativeto the European Parliament"31andtwo parliaments chose the title of "The (Permanent) Representativeto the EUInstitutions"32. The rest of parliaments and chambers either chose not to use any specifictitle or to use such unique titles as: "The Representative in Brussels", "The Head of thePermanent Office to the EU" or the "Liaison Officer".It is worthwhile noticing that in almost half of the cases (15 out of 33) parliaments andchambers chose to use the word "permanent" in the title of their representatives to reflect thefact that they have representatives posted in Brussels on a permanent basis in contrast to aadhoc,short-term visits to the EU Institutions.3.4. Term in officeThe practice of national parliaments and chambers to appoint their representatives in Brusselsfor a certain term in office also varies. The replies of parliaments indicate that a larger part ofthe representatives (18 out of 33) are nominated for a fixed term in office which varies fromtwo to eight years.On average,the term in office of the representatives isthree years,eitherrenewable or non-renewable. Regardless of the fact that the fixed-term-in-office nominationsmay or may not be renewed, they offer the permanent representatives a degree of certainty asto their future.On the other hand, almost half of the representatives (15 out of 33) are appointed to the postwithout a predetermined term in office, i.e. on a case-by-case basis, depending on the termsof the "contract" between the official and the nominating parliament or chamber. This mayleave a certain degree of uncertainty as to the representative's future.3.5. Coordination of activities of the representatives of bicameral parliamentsPresently five bicameral parliaments: the Belgian, the Czech, the French, the Polish and theUK Parliaments have two representatives in Brussels, representing each of their chambers.Judging from the replies of the chambers, the general rule is that the representatives of thechambers of the bicameral parliaments do not engage in any formal coordination of theiractivities and work to the needs and demands of their respective chambers. Without doubtthis practice is predetermined by the internal constitutional order of the Member States inquestion.However, there are exceptions. For instance, during the Presidency of the EU a high degreeof coordination of the activities of both representatives is necessitated by an increasedworkload. For instance, administrative coordination both in Paris and in Brussels (between30

The Austrian Parliament, the DanishFolketing,the FrenchAssemblée nationale,the GermanBundestag,theIrishHouses of the Oireachtas,the ItalianSenato della Repubblica,the LatvianSaeima,the LithuanianSeimas,the DutchStates-General,the PolishSejm,the PolishSenat,the PortugueseAssembleia da República,and theUKHouse of Commons.31The BelgianChambre des Représentants,the BelgianSénat,the BulgarianNarodno Sabranie,theVouli TonAntiprosoponof Cyprus, the CzechPoslanecká Snĕmovna,the EstonianRiigikogu,and the SlovenianDržavnizbor.32The LuxembourgChambre des Députés,the SwedishRiksdag.

25

the representatives of the FrenchAssemblée nationaleand theSénat)during the FrenchPresidency of the EU in the second half of 2008 was achieved through a regular dialoguebetween the political authorities of the two Chambers. Following the Presidency, the tworepresentatives maintained the practice of informal daily exchange of information, especiallyin case of events involving both Chambers.Similar coordination of activities, even ifad hoc,is evident in the case of the current CzechPresidency of the EU. In addition to the representative of the CzechSenátin Brussels, theCzechPoslanecká sněmovnasent its own representative to Brussels primarily to serve as amember of the COSAC Secretariat. However, during the Presidency the tasks of therepresentative of thePoslanecká sněmovnawere broadened to include some of the"traditional" functions of the national parliament representative to the EU.Also, replies indicate that in cases of inter-parliamentary activities, visits of the Members ofParliament to Brussels or study visits of parliamentary officials, permanent representatives ofbicameral parliaments tend to closely cooperate on an informal basis. This is true in case ofthe PolishSejmand theSenat,the CzechPoslanecká sněmovnaand theSenátas well as theUKHouse of Commonsand theHouse of Lords.3.6 Main functionsThe responses to the questionnaire verify that the representatives of national parliamentsperform alarge variety of "main" functions.This goes for the representativesindividually,but also in a comparison between them.It can be assumed, that had the respondents beenasked to enumerate all functions of their representatives, the variation would have been evenlarger.However, two fields of work are mentioned by almost everyone as being (part of) the mainfunctions of their respective representatives. One isreporting on political events anddevelopments in the EU,the other isto assist Members of Parliamentwhen they attendinter-parliamentary meetingsorganised in Brussels.Although reporting is indicated as a core function for all representatives, it is clear from theanswers that the mode and frequency of reporting, choice of topics, etc. differs considerably(see under 3.8 below).The variation in what parliamentary representatives do in relation to different types ofinter-parliamentarymeetings is smaller. However, in addition to being present at the meetingitself, being on hand withinformation on the topic(s)discussed and/or providingpracticalassistanceto the Members of Parliament attending, representatives are sometimes involvedindrafting of background documents.They oftenwrite reportsof the inter-parliamentarymeetings, either on their own, or in cooperation with officials accompanying the Members ofParliament.Organising visits by Members or officialsof "their" parliament to EU Institutions inBrussels or Strasbourg is also frequently mentioned. These visits are of different characters.On the level of Members of Parliament they may be ranging from visits of a fullparliamentary committee, to those of a single Member of Parliament, perhaps arapporteurinthe national parliament concerned. Similarly, programmes may range from several meetings,

26

over a few days and with a large number of politicians and high-level officials, down to onesingle meeting on a particular issue or otherwise for one specific purpose.In about half the responses"contacts", "exchange of information", or "co-ordination"withrepresentatives in Brussels ofother national parliamentsare mentioned among the"main functions". In many of these cases, the answers indicate that the importance of thisfunction isexpected to increase,in view of the enhanced role of national parliamentsenvisaged in the Treaty of Lisbon. For instance, theHouse of Representativesof Cyprusmentions "the need to have a stronger link between the House of Representatives, theEuropean Parliament and the group of the representatives of the national parliaments alreadyin Brussels, especially in view of the role of national parliaments envisaged in the Treaty ofLisbon."A few national parliaments, among them the FrenchSenát,the SwedishRiksdagand the UKHouse of Lords,mention that one of the main tasks of its representative is todisseminateinformation concerning the activities and positionstaken by those parliaments. Generally,it is not specified to whom such information should be given. One interpretation of thiswould be that, by and large, it is left to the representative to decide, based on his/herknowledge of persons and institutions in Brussels, who might be the appropriate recipient(s).In any case, such information concerning national parliaments' position seems to be given ona case-by-case basis.Also, in a number of cases,liaising with the respective country's Members of theEuropean Parliamentis mentioned among the main tasks. Presumably, passing informationto them concerning developments in national parliament is one element. More important,however, seems to be for the representative to facilitate a flow of information betweenMembers of the European Parliament and Members (or Committees) of the nationalparliament dealing with the same issue.Organising and contributing totraining courses for staffof the respective nationalparliament is another function of the representative that is mentioned by a few of therespondents. For instance, the representative of the IrishHouses of Oireachtasprovideslogistical support as well as input to EU related training.The Parliaments of Austria and of the Netherlands also mention the more general function ofnetworking.Some representatives, such as those of the FrenchAssemblée nationale,theGermanBundestag,and the ItalianSenato della Repubblica,are specifically charged withupholding contacts outside the EU Institutions as such - with think tanks, academics, lobbygroups, etc. In some cases, such as the BulgarianNarodno Sabranie,the LatvianSaeimaandthe SlovakianNárodna Rada,representatives are working in cooperation with the PermanentRepresentation of the country to the EU.3.7 Focus of attentionMany respondents have found itdifficult to indicateon which type(s) of work theirrepresentative focuses his/her attention (apart from referring to the "main functions"),or toquantify,even in rough terms, theamount of time used for different functions.Many,such as the CzechSenát,state that although reporting and channelling information isgenerally the main task, other matters may dominate and become the main task during acertain period. Another factor might be that for many parliaments the experience of having a

27