Udvalget for Udlændinge- og Integrationspolitik 2010-11 (1. samling)

L 168 Bilag 7

Offentligt

Country Report Denmarkby Eva Ersbøll and Laura Katrine Gravesen

The INTEC project:Integration and Naturalisation tests: the new way toEuropean CitizenshipThis report is part of a comparative study in nine Member Stateson the national policies concerning integration and naturalisationtests and their effects on integration.

Financed by the European Integration Fund

December 2010Centre for Migration LawRadboud University NijmegenNetherlands

DENMARK

Introduction

This research report primarily examines the actual effects of recent legislationon compulsory integration courses and tests as a condition for access to apermanent residence permit and naturalisation. Although Denmark has in-troduced an immigration test as a condition for admission for family reunifi-cation, this test did only recently enter into force (as of 15 November 2010),and its effects are not yet known. Therefore, Chapter 2 ‘Integration test as acondition for admission’ only contains a description of the Danish legislationon the introduction of an ‘immigration test’ and some background informa-tion (arguments, problems, media attention, public discussion etc.), whileChapters 3 and 4 on integration tests as a condition for permanent residenceand naturalisation, deal additionally with the effects of the two tests evalu-ated on the basis of interviews with 26 migrants,1five representatives fromlanguage schools, five representatives from immigrant organisations and fiveofficials responsible for the application of the integration and naturalisationlegislation.Since the research was carried out within a very short period (from midFebruary 2010 to July 2010) and because limited resources were available,2we were not able to select the respondents evenly on the basis of nationality,age, gender, socio-economic background, etc. Accordingly, among the mi-grants interviewed, there were more than twice as many women as men (dis-tribution: 64 - 36 per cent for permanent residence and 73 - 17 per cent fornaturalisation)3and the respondents were relatively young (on average intheir early thirties) with a middle to high educational background (less thana quarter had a low educational background). Most of the applicants forpermanent residence settled in Denmark for family reunification while al-most half of the applicants for naturalisation were born and/or raised inDenmark. In general, the migrants interviewed represent a variety of coun-tries; see Annex 1.

1

2

3

As it appears from the annex, 14 migrants were interviewed about their experiences re-garding access to permanent residence and 12 about their experiences regarding accessto naturalisation.Due to the Danish opt-out from the EU Justice and Home Affairs, Denmark cannot re-ceive money from the European Fund for the Integration of Third Country Nationals,but has received part-payment from the Radboud University Nijmegen.This may, however, reflect a general tendency at the language schools where womenand younger foreigners generally are in the majority, see below under 3.3.

3

DENMARK

Particulars about the RespondentsFinding migrant interviewees turned out to be more difficult than firstthought. As will appear from the following chapters, the Danish languagetests required for permanent residence and naturalisation are not tests estab-lished for the purpose of approving applications for permanent residenceand naturalisation. The Danish language courses and the Danish languagetests are part of an introductory programme offered to newcomers after theirarrival and normally lasting for three years. Migrants who have passed alanguage examination after three years of schooling will normally have towait an additional number of years before they can apply for permanentresidence (at the time of the interviews, the general residence requirement forpermanent residence was seven years and the residence requirement fornaturalisation nine years). Therefore, applicants for permanent residence andnaturalisation are normally not found on the language school courses. Someapplicants who have not passed the relevant examination may of course at-tend a language school to sit an examination (a test) in connection with theirapplication for either permanent residence or naturalisation; however, sincethe language examinations take place every six months (May/June and No-vember/December) – and since we had to finalise the INTEC research projectby the end of June, we had to commence the interview work in March.Thus, instead of finding migrant respondents at the language schools, wetried to find the respondents through the administrative authorities dealingwith applications for permanent residence and naturalisation. A job centre inthe Municipality of Copenhagen (dealing with applications for permanentresidence) agreed to send out letters to all the migrants who had applied forpermanent residence within a certain period (the last few months of 2009).Using this method, we made contacts with seven migrants (50 per cent of ourmigrant respondents). The advantage of this method was that the applicantswere randomly chosen; the only common features were that the respondents– at a certain point in time – had lived in the Municipality of Copenhagenand that they had contacted us at their own initiative after having receivedthe letter from the job centre in Copenhagen.The process of finding respondents for interviews concerning access topermanent residence was characterised by what is known as the ‘snowballeffect’; by contacting people working in the field, new possibilities emerged.Thus, through language teachers at a preparatory course for the naturalisa-tion test, we were given the possibility of interviewing migrants at a lan-guage course held at a major international company and here, by case- to-case contact, we found the opportunity to conduct interviews at another lan-guage school. In this way, we interviewed a total off seven more respon-dents: two at the international company and five at the language school.These respondents were from the area of Copenhagen, but with differenteducational backgrounds, nationalities, residence permits, etc.4

DENMARK

As for naturalisation, it was easier to find the applicants. An applicationfor naturalisation has to be submitted to the police who after its examinationforward it to the Ministry of Integration. We made arrangements with one ofthe local police stations in Copenhagen handling naturalisation cases. In ad-dition, we made an appointment with a language school in the vicinity ofCopenhagen where, as of April 2010, migrants could attend a preparatorycourse for the naturalisation test. Five of the twelve applicants for naturalisa-tion were interviewed at the police station, four at the preparatory courseand three through other contacts (snowball effect). These respondents alsohave a different background.The characteristics of all respondents are described in Annex 1.It is worth noting that we had difficulties finding migrants who hadgiven up applying for a permanent residence permit or naturalisation. Thereis every indication that migrants are very persistent in their desire to acquirea permanent residence permit and/or citizenship. However, as regards per-manent residence we interviewed two and, regarding naturalisation, threemigrants for whom fulfilling the requirements presented great difficulties.While selecting immigrant organisations, we asked different people withlong-term experience within the field which organisations would be the mostrelevant and representative to interview. The selected organisations are theCouncil for Ethnic Minorities, the Somali Network in Denmark, the Docu-mentation and Advisory Centre on Racial Discrimination, Copenhagen LegalAid4and the Danish Refugee Council.The same method was used for selecting language schools. The chosenschools are a large private and a large public language school, a schoolowned by the Danish Refugee Council, a small private school in the provinceand a large provincial language centre covering ten municipalities.The officials interviewed represent the police, the central administration(the Immigration Service and the Ministry of Integration) and the municipali-ties. Regarding naturalisation, we interviewed an employee in the Ministryof Integration’s Naturalisation Office5and a police officer in Copenhagen.Regarding permanent residence we interviewed an employee from the Officefor Family Reunification, Passports and Extension of Residence Permits inthe Immigration Service, two employees of the Municipality of Copenhagen,the Job Office,6and an employee from a smaller suburban municipality in thevicinity of Copenhagen.

456

Copenhagen Legal Aid is based on the principle of political neutrality; therefore, thisorganisation has not made any statement that may reflect a political opinion.The interview with the Naturalisation Office was conducted in writing: the interviewform is completed by an official from the Naturalisation Office.This interview counts as one interview.

5

DENMARK

Research MethodThe Danish legislation, the legislative debate and the literature, etc, on inte-gration tests are analysed and 41 interviews based on the common INTECquestionnaires are evaluated. Before describing the results, some reservationshave to be made.A number of the migrants interviewed did not have sufficient languageskills to understand and/or answer all the questions in the interview guide.This problem was most noticeable in relation to applicants for permanentresidence. Furthermore, even during interviews with migrants with goodDanish language skills, comprehension gaps arose as to some of the ques-tions. These problems may have influenced the overall analysis of the inter-views since the viewpoints of the most articulated may have prevailed. Asalready mentioned, the comprehension problem was the least evident duringthe interviews with applicants for naturalisation, although a few had troubleboth understanding the questions and expressing themselves. In such situa-tions with comprehension problems, the interviews centred more on the re-spondents’ experiences and stories and less on getting answers to the ques-tions in the interview guide.From the very beginning it was our intention to record all interviews.Very soon, however, we realised that many applicants for both permanentresidence and naturalisation felt insecure being recorded during the inter-views. Therefore, only a few interviews with applicants were recorded; con-sequently, the summaries of the interviews with migrants are less detailed,since it turned out to be difficult for the interviewer taking extensive notesduring the interviews.A related problem was that the location of the interviews seemed to in-fluence the openness of the migrants. This effect became especially clear dur-ing the interviews conducted at the police station. We had the impressionthat some of the applicants for naturalisation were made uneasy by the merefact that their applications were being handled by the police and that addi-tionally, they felt that their answers during the interview with us might in-fluence the outcome of their application for naturalisation. As to the mi-grants’ openness, we had the reverse experience while interviewing migrantsin their own homes where they were fairly outspoken and open-minded.All the interviews were conducted by one person.7This may influencethe perception and analysis of the interviews both negatively and positively.Such an effect may be generated since interpretation and analysis during theinterview situation may influence the final analysis and interpretation of theinterviews. This may broaden the analysis but, on the other hand, one draw-

7

All interviews were conducted by Laura Katrine Gravesen; Eva Ersbøll did howeverparticipated in a small number of interviews.

6

DENMARK

back may be that the interviewer, because of her interpretation during the in-terviews, may leave out some relevant information.The results of the interviews can not be used for statistic generalisations.However, they do in our opinion provide a valuable insight into the differentexperiences and opinions of the migrants, officials, language teachers andorganisations and they may provide a unique understanding of the field ofthe naturalisation- and integration test. Thus, the experiences and the prob-lems expressed by the respondents in the interviews may shed light on someareas relevant for the whole group of immigrants in Denmark.

Existing Danish LiteratureSo far there, not much literature has been published on Danish integrationand naturalisation tests. However, the language requirement for naturalisa-tion and the citizenship test are mentioned in Eva Ersbøll’sDansk indfødsret iinternational og historisk belysning (2008),in Silvia Adamo: Northern Exposure:The New Danish Model of Citizenship Test, in theInternational Journal onMulticultural Societies008 vol. 10 no. 1, pp. 10-28, UNESCO and in SilviaAdamo’s PhD thesis:Citizenship Law and the Challenge of Multiculturalism, TheCase of Denmark(2009; not yet published). Furthermore, the language re-quirement for naturalisation and the citizenship test are described on theEUDO website, the Danish country profile by Eva Ersbøll: http://eudo-citizenship.eu/docs/CountryReports/Denmark.pdf . Moreover, the Danish in-tegration tests, etc, are discussed in Eva Ersbøll: On trial in Denmark, inRicky van Oers, Eva Ersbøll and Dora Kostakopoulou:A Re-definition of Be-longing? Language and Integration Tests in Europe(2010). Additionally, someforeign literature refers to the Danish tests, including others Anja Wiesbrock:Legal Migration in the European Union, Ten Years after Tampere(2009). Added tothis, several studies examine foreigners’ integration in Denmark, including‘IntegrationStatus -10 års fremgang – og hvad nu?’8The effects of the Danishlanguage courses under the Danish for Adult Immigrants scheme are alsodiscussed in a number of publications, including a publication concerningimmigrant women learning Danish:Indvandrerkvinder i danskuddannelsen(AKF Working paper 2010 www.akf.dk ).

8

Catinét A/S (2009) www.catinet.dk.

7

DENMARK

Chapter 1: Overview

As will become evident below, a close relationship exists between the Danishlegislation on integration, Danish language education and integration andnaturalisation tests, respectively.

1.1

Legislation on Integration

The first DanishAct on the Integration of Aliens in Denmarkwas adopted in1998 and entered into force on 1 January 1999.9The Integration Act appliedto both refugees and immigrants. The aim was to make it possible through anintegration effort for, newly-arrived refugees and immigrants to become ac-tive participants in the Danish society as a whole, self-supporting and withan understanding of Danish fundamental values and norms. The Act as-signed the municipalities overall responsibility for the integration efforts(formerly handled by the Danish Refugee Council).Newly arrived foreigners were offered an introductory programmecomprising a course in societal knowledge, a Danish language course and‘activation’, normally lasting three years. The target groups were foreigners,defined as refugees and family reunified immigrants, legally resident inDenmark. Nationals from the other Nordic countries and the EC/EEA werenot covered, nor were foreigners affected by the EC rules on visa exemptionand the abolition of entry and visa restrictions in connection with freemovement rights.10As a rule, foreigners offered an introductory programme were entitled tointroductory aid for a period of up to three years.11At that time the introduc-tory aid amounted to a maximum of 5000 DKK (EUR 672) per month for sin-gle people and 7000 DKK (EUR 940) for persons supporting minor children.If a foreigner refused to participate in the introductory programme for nogood reason, the municipality could reduce or withdraw the introductoryaid; similarly, a reduction was possible if a foreigner refused to attend with-out justification. Moreover, lack of attendance could lead to refusal of an ap-plication for permanent residence.91011Act no. 474 of 1 July 1998.See now section 2(3) in Consolidation no. 1593 of 14 December 2007 of the Act on the In-tegration of Aliens in Denmark (the Integration Act).Introductory aid was conditional upon certain income requirements and family reuni-fied foreigners were not entitled to the allowance if their sponsor had guaranteed theirmaintenance and their residence permit was conditional upon this person’s support.

9

DENMARK

The Danish language course was a key element of the integration pro-gramme. According to the 1998 Act, the extent and content of the introduc-tory programme, including the Danish language course, were to be laiddown in an individual ‘action plan’ based on the abilities and skills of eachindividual foreigner with the explicit objective of introducing him or her tothe labour marked or to further education.In January 2002, the new Liberal-Conservative government that cameinto power in 2001 adopted a ‘new aliens policy’.12This policy was based onthe following three fundamental principles: Denmark’s international obliga-tions are to be respected; the number of immigrants is to be limited and therequirement that immigrants be self-supporting is to be strengthened.Accordingly, in February 2002, the new Minister for Integration pre-sented a Bill amending the Integration Act in order to implement the newaliens policy. With the adoption of the amendment, foreigners and their localcouncils became obliged to enter into ‘an individual contract’ (instead of theformer ‘action plan’) in order to guarantee the quality of the introductoryprogramme. The contract was to specify that foreigners offered an introduc-tory programme had a duty to participate actively in the different pro-gramme elements.13The different elements were to be laid down in the con-tract on the basis of an assessment of the foreigner’s situation, skills, back-ground and needs (Section 16(3), cf. Section 19). Furthermore, the contractwas to specify the sanctions applicable to the legislation in situations wherethe foreigner failed to appear or rejected one or more of the activities agreedupon (or decided) in the individual contract. The consequences included areduction or suspension of the introductory aid (sections 30 and 31) and alack of options for obtaining a permanent residence permit (Section 11(7) (2)of the Aliens Act (as amended in 2002).14The Integration Act has since been amended several times. In 2006 it wasamended on the basis of an integration agreement which the governmenthad entered in 2005 into with the Danish People’s Party and the Social De-mocrats.15The basic idea was that foreigners should meet the same expecta-tions and requirements as other citizens and that they and their descendantsshould have the same fair opportunities as others. Education was seen as aprecondition for integration and foreigners should make an effort, take re-sponsibility for and demonstrate their will to integrate, find employment andbecome self-sufficient.According to the 2006-amendments it was established that a foreigner’s‘integration contract’ lasts until he or she has acquired a permanent residencepermit (Section 19(8)); the integration contract replaced the ‘individual con-12131415En ny udlændingepolitik (A new aliens policy), 17 January 2002.Act no. 364 of 6 June 2002.Amended by Act no. 365 of 6 June 2002.See Act no. 243 of 27 March 2006

10

DENMARK

tract’. Furthermore, it became a requirement that foreigners must sign andthereby recognise the values stated in a ‘Declaration on integration and ac-tive citizenship’. In principle, this declaration is not legally binding; its pur-pose is to render Danish values visible and indicate that the society expectsforeigners to make an effort to integrate as participating and contributingcitizens, equal to other citizens.16The latest amendment of the Integration Act was adopted in Parliamenton 25 May 2010.17The aim of this amendment is to adjust the Act to achanged migration pattern and new challenges as regards migration. Thenumber of foreigners who have emigrated to Denmark for the purposes ofemployment and studies has more than tripled since 2001, while the num-bers of refugees and those seeking family reunification have fallen to belowone third of the 2001-level. The government and the Danish People’s Party(which entered into an agreement with the government regarding thechanges on 15 March 2010), want to ensure that the integration efforts in-clude all foreigners, not exclusively refugees and foreigners seeking familyreunification. Moreover, the integration offers must be adapted to the newgroup of immigrants.Thus, as of 1 August 2010 the scope of the Integration Act has been ex-tended to include labour migrants and their families plus EU migrants. Con-sequently, the municipalities have been assigned responsibility for all newlyarrived foreigners. There is to be more focus on active citizenship, and withinfour months of a local council having taken over responsibility for a for-eigner, that person must be able to begin a course on Danish society, cultureand history: an ‘active citizenship course’(Section 22). Moreover, employ-ment promotion and tailor-made offers to the extended target groups of theIntegration Act will be emphasised, and the link between the integration ef-forts and the right to permanent residence will be explained. For instance, itis explicitly spelled out in the Objects clause, Section 1, paragraph 4, that oneof the aims of the Integration Act is to ensure that newcomers be made awarethat successful integration is a precondition for access to a permanent resi-dence permit (see below under 1.4 and 3.1).The integration options will follow two paths: anintegration programmefor refugees and foreigners arriving for family reunification and a less inten-siveintroductory coursefor labour migrants and other migrants with (pre-sumably) more resources. Normally, the duration of the integration pro-gramme and the introductory course will have a maximum of three years,but a course must be completed as quickly as possible. As for content and

16

17

It was made a condition for acquisition of a permanent residence permit that the for-eigner signed the integration contract as well as the declaration on integration and ac-tive citizenship in Danish society (section 19(1) (1)), see Act no. 243 of 27 March 2006.Act no. 571 of 31 May 2010.

11

DENMARK

length, both the integration programme and the introductory course will betailor-made to each individual foreigner.It should be noted that persons interviewed for this project have not (yet)been subjected to the new rules adopted on 25 May 2010.

1.2

Legislation on Danish Language Education

As previously mentioned, a close link exists between the legislation on inte-gration and the legislation on Danish language education. Thus, in 1998, con-currently with the adoption of the Integration Act, anAct on Teaching Danishas a Second Language for Adult Foreigners and Others and Language Centreswasadopted.18Like the Integration Act, the Education Act entered into force on 1January 1999. Danish language tuition was to be provided at languageschools with a view to securing appropriate educational options for partici-pants with very diverse backgrounds, abilities and needs. The educationalfacilities were to be accredited and streamlined and the number of weeklyperiods/lessons was to be increased (by 30 per cent).In 2003, the newly established Ministry of Integration presented a neweducation Act to Parliament with a view to making the Danish education sys-tem more effective in order to secure the integration of foreigners into the la-bour market. Among other things education in Danish culture and societywas strengthened. (The Danish courses provide both knowledge of Danishlanguage and knowledge of Danish society, etc.)The newAct on Danish Courses for Adult Aliens and Othersentered intoforce on 1 January 2004.19According to the Act, foreigners are generally of-fered a Danish language course lasting three years: Danish Course 1 (DC1),Danish Course 2 (DC2) or Danish Course 3 (DC3).20The scope of each of thethree Danish courses corresponds to 1.2 years’ full-time study. The coursesare split into 6 six-month modules with specific targets (on average, eachmodule corresponds to 0.2 years’ full-time study). Enrolment in a moduleother than the first module assumes that the targets of the preceding mod-ule(s) have been achieved.DC1 attaches importance to oral Danish. However, students do have tolearn how to read and write a simple text in Danish. The object of DC1 is toqualify the students for unskilled labour and active citizenship.In DC2, students learn to understand, speak and read Danish and towrite some texts. The object is to qualify students for the labour market, ac-

181920

Cf. Consolidation Act no 975 of 25 October 2000 from the Ministry of Education.Act no. 375 of 28 May 2003.Foreigners are also offered a course at a higher level, leading to the Higher EducationExamination (the study test).

12

DENMARK

tive citizenship and participation in qualifying labour market courses orother vocational training alongside Danish colleagues.In DC3, the speed and level of Danish are higher than in DC2. Studentslearn to put problems into perspective and to incorporate general cultural,historical and societal knowledge. They learn to vary their spoken and writ-ten Danish language in order to be able to argue in favour of their personalattitudes and viewpoints. The object of DC3 is to qualify students for the la-bour market or for further education – and active citizenship.All three courses culminate in tests in oral communication, as well asreading comprehension and written presentation. The Danish 1 Examination(D1E) is comparable to ALTE level 1/Council of Europe level (CEFR) A2. TheDanish 2 examination (D2E) is comparable to ALTE level 2/CEFR B1. D2E in-cludes an assessment of whether the students can express themselves in flu-ent, understandable and relevant language with a certain complexity andcorrectness. The Danish 3 Examination (D3E) is comparable to ALTE level3/CEFR B2. D3E comprises an assessment of whether the students can ex-press themselves relevantly and understandably using fairly nuanced andcomplex language with a relatively high degree of accuracy. In writing, thestudents must be able to discuss a subject, describe attitudes and viewpoints,elaborate, give reasons and summarise.21The three Danish language courses target foreigners according to theirprevious schooling, i.e. no schooling, limited schooling and extensive school-ing, respectively. DC1 is intended for students who have little or no educa-tional background and have not learned to read and write in their mothertongue (and Latin script illiterates who do not understand European nota-tion). DC2 is intended for students with some educational background intheir country of origin who are expected to learn Danish as a second lan-guage fairly slowly. DC3 is intended for students with lower or upper secon-dary or higher education in their country of origin (for instance vocationaltraining, grammar school or long cycle higher education), who are expectedto learn Danish as a second language fairly rapidly.22Students with special needs, for instance as a result of dyslexia, otherlearning difficulties, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), other psychiatricillnesses or brain injuries, etc., are offered tuition in small groups or – in very21SeeBekendtgørelse om prøver inden for danskuddannelse til voksne udlændinge m.f.(Regula-tion No. 912 of 28 September 2005 on tests within Danish education for adult foreignersand others); D3E may be taken by students who have completed the first five modulesof DC3. Students who complete all 6 modules can take the higher education examina-tion (the study test); since success in this examination is not an ‘integration requirement’it will not be discussed further.The aim of the test is to ensure that students have sufficient knowledge of Danish lan-guage to render them capable of coping well in the Danish educational system. Thus,reading and writing are the main focus. The students are supposed to be able to expressa reasoned opinion on public matters in fluent Danish.

22

13

DENMARK

special cases – individual tuition. These students may also be offered special(compensatory) education before starting a Danish course, with the right todeferment of the three-year Danish education period.Furthermore, foreigners have the option to extend the three-year periodof free Danish language tuition if, for instance as a result of full-time work,illness or childbirth, they are prevented from participating in courses for thethree-year period. In general, the courses are relatively flexible in terms oftime, place and content in order to enhance interaction with the students'employment, activities or training; among other things, students may followclasses outside normal working hours.It remains to be said that, with the adoption to the recent amendments tothe Integration Act, Section 2 of the Act on Danish Courses for Adult Aliensand Others, concerning the personal scope of the Act, was also amended,providing for access to Danish courses for all foreigners who have reachedthe age of 18 and have a residence permit or other permission to hold habit-ual, legal residence in Denmark, including persons with EU registrations andEU residence cards.

1.3

Legislation on Language and Integration Tests as a Condition forBeing Granted a Permanent Residence Permit and Naturalisation

At the same time as both the adoption and the amendments to the Integra-tion Act and the Act on Danish Language Courses, the Aliens Act and theDanish citizenship legislation have also been amended.

1.3.1 The Aliens Act’s Integration Requirements regarding PermanentResidenceIn 1998, the Aliens Act was amended with a view to making it a condition foraccess to permanent residence, as of 1 January 1999, that the applicant hascompleted an introductory course (established according to the IntegrationAct). By an amendment to the Aliens Act in 2002, the requirement for per-manent residence was extended to include a language examination. No fixedlevel was set at that time; applicants simply had to pass the examination atthe course in which they were enrolled (or – if they had not been enrolled ata course – an examination at a suitable level). However, by an amendment in2007, the required language level was fixed at D2E, comparable to the Euro-pean level B1 (part of an ‘integration examination’, see below under 3.1). As aresult of the transitional rules, the 1998- and 2002-requirements co-existedwith the 2007-requirements and were applied to applicants who had appliedfor a residence permit when the respective Acts were in force and had com-14

DENMARK

pleted an introductory programme and/or passed a language examinationbefore 29 November 2006.23However, on 25 May 2010, the Aliens Act wasamended, together with the Integration Act and the Act on Danish LanguageCourses and according to the amendments, which entered into force as of 2June 2010,allapplicants for permanent residence are subjected to the very re-strictive requirements of the 2010-Act, see Chapter 3 below.

1.3.2 The Naturalisation Circular’s Integration RequirementsIn 2002 the government and the Danish People’s Party agreed that as a ruleapplicants for naturalisation should document their Danish language abili-ties by passing a language examination at a language school at a level com-parable to D2E (B1).24In 2005, it was agreed that the required level would beraised to D3E (B2) and at the same time, it was decided that a citizenship testwould be introduced, which came into force in May 2007. In 2008, the citi-zenship test requirements were strengthened and, moreover, it was notlonger sufficient simply to pass the D3E examination (in order to pass, amark of at least 6 on a 13- point scale or 2 on a 7-step scale is required). Fromnow on, an average mark of at least 7 (on the 13 -point scale) or 4 (on the 7-step scale) is required.

1.4

The Relationship between the Different Tests

As already mentioned, close interaction exists between immigration, integra-tion and language policies. The first DanishAct on Integrationwas adoptedconcurrently with the adoption of theAct on Teaching Danish as a Second Lan-guage for Adult Foreigners and Others and Language Centresand theAliens Actwas amended at the same time. All the interrelated new rules entered intoforce as of 1 January 1999. In 2002 it was decided that both applicants forpermanent residence and applicants for naturalisation should documenttheir Danish language abilities by passing a language examination at a lan-guage centre (no fixed level for permanent residence, while an examinationat level B1 was required for naturalisation). Both the requirement for perma-nent residence and the requirement for naturalisation were strengthenedaround 2006 (the level was fixed at B1 for permanent residence and B2 fornaturalisation). At the same time, a naturalisation test was introduced –modelled on the Dutch societal knowledge test. The language and societalknowledge requirements for naturalisation were strengthened in 2008, and2324The day when the Bill amending the Aliens Act was presented in Parliament.The level was a little below B1, but this was changed by the Act on Danish Coursesfrom 2003.

15

DENMARK

the general requirements for permanent residence were strengthened in 2010when, among other things, an active citizenship test was introduced, mod-elled on the naturalisation test.25In some ways the requirements for perma-nent residence are more restrictive than the requirements for naturalisation,for instance regarding the requirement for full-time employment. However,the requirements for permanent residence and the requirements for naturali-sation apply independently: the fulfilment of the former does not exempt anapplicant from fulfilling the latter.In general, the arguments with regard to the different tests have more orless been of the same nature. However, the view of ‘immigrant responsibil-ity’ has shifted. In 1998 the public responsibility for providing immigrantswith opportunities to integrate on an equal footing with other citizens wasemphasised. Since then, the demands on immigrants to take responsibilityfor their own integration and to document their good will to integrate haveincreased. It is increasingly being stated that immigrants themselves have aduty towards their own integration and that they must respect Danish soci-ety’s values and norms and must meet expectations, especially that success-ful integration requires an active individual effort. This has culminated inlegislation based on the idea that ‘permanent residence is reserved for for-eigners who integrate’, that ‘results count’ and also that ‘citizenship must beearned’.The aim of promoting better integration is mentioned in the preparatorywork to the 2010 amendment of the Integration Act. This explicitly statesthat, in order to encourage foreigners to integrate into the Danish society andto highlight the link between access to permanent residence and integration,foreigners signing an integration contract must be made aware of the re-quirements for permanent residence. Furthermore, foreigners on the activecitizen course must be taught about the conditions and it should be stressedthat ‘poorly integrated foreigners cannot acquire a permanent residencepermit’.The official message is that what matters is the immigrant’s desire forin-tegration;however, immigrants with little ‘integrationcapacity’are at a disad-vantage.This became alarmingly clear with the 2010 amendments to the AliensAct. Apparently, the Danish government now defines ‘integrated foreigners’as foreigners who can fulfil ten integration requirements comprising, amongother things, full- time employment, good Danish language skills and ‘activecitizenship’. Many immigrants who, informally, are considered well-integrated will not be able to fulfil these criteria, whether they be hard work-ing people with too little spare time for studying or in the process of trainingwith no possibilities for taking up full time- employment.

25

The active citizenship test is expected to be implemented in mid-2011.

16

DENMARK

Assessing whether the integration test requirements have led to better in-tegration based on such a narrow definition of ‘integration’ may prove diffi-cult.

17

DENMARK

Chapter 2: Integration test as a condition for admission2.1 The test2.1.1 Introduction of the testBy an amendment to the Aliens Act adopted on 25 April 2007,26it was de-cided that an immigration test would be established for foreigners applyingfor family reunification and for religious preachers applying for (extensionof) a residence permit. The decision followed the Dutch example regardingthe establishment of an integration test to be taken abroad before admission.According to the preparatory report to the Bill, the purpose was tostrengthen the individual foreigner’s possibilities for successful and rapid in-tegration into Danish society. The perception was that foreigners who hadpassed an immigration test would be better prepared for the introductoryprogramme to which they were to be subjected as newcomers to Denmark.Apart from being a supplement to the ordinary language courses, the immi-gration test should help ensure that foreigners took responsibility at the ear-liest opportunity for their own integration and documented their motivationand dire to become part of Danish society.After the adoption of the immigration test, a working group was set upwith a view to conducting a pre-analysis of the implementation of the test.Based on the working group’s conclusion that it would be very costly to es-tablish a testing system abroad (comprising relatively few applicants frommany different countries), the government and the Danish People’s Partyagreed that applicants for family reunification should take the immigrationtest in Denmark – after having received pre-recognition regarding their ful-filment of the other conditions for admission.27This change required anamendment of the 2007 Act. A Bill in this respect was presented in Parlia-ment on 10 December 2009 and adopted on 15 April 2010 with 107 votes forand 7 votes against (only the two small parties, the Social Liberals and theRed-Green Alliance, voted against).28The Act authorised the Minister for In-tegration to determine when the immigration test was to come into force.Eventually, the date was set to 15 November 2010.

2627

28

Act no. 379 of 25 April 2007.Rapport fra arbejdsgruppen vedrørende foranalyse om implementering af Indvan-dringsprøve, September 2007. According to the analysis, around 1500 - 2000 applicantswere expected to take the case and most of them (around 70 per cent) would alreadystay in Denmark being issued a tourist visa or another kind of residence permit.Act no. 400 of 21 April 2010.

19

DENMARK

2.1.2 Target Groups, ExemptionsApart from EU/EEA citizens and foreign citizens seeing family reunificationwith a Turkish citizen living in Denmark who is economically active as anemployee, self-employed person or service provider,29the immigration testrequirement includes in principle all foreigners applying for reunificationwith a spouse or partner (and religious preachers).30Exemption from the test requirement is possible under certain specialcircumstances, for instance where the sponsor is a refugee who cannot takeup residence in his or her country of origin due to the risk of persecution orwhere the sponsor’s personal conditions call for an exemption. In all caseswhere a refusal will constitute a violation of the European Convention onHuman Rights (ECHR), exemption must be granted. In general, the test re-quirement does not apply to foreigners who cannot fulfil the requirementsdue to serious illness or handicap, including PTSD. Furthermore, the re-quirement does not apply to foreigners who are granted family reunificationaccording to special practice, including foreigners applying for family reuni-fication with a sponsor with a residence permit granted for occupational oreducational reasons. Lastly, the test requirement does not apply if the for-eigner already has a sound knowledge of Danish and Denmark, for instanceacquired while staying in Denmark for a number of years; exemption will begranted if the foreigner has lived in Denmark for at least five years and fulfilsthe Danish language requirement for permanent residence.

2.1.3 Content, Level, etc.The immigration test is an oral test. It consists of a Danish language test anda societal knowledge test. The entire immigration test takes approximately 30minutes.The language test comprises 40 questions and implies that the applicantsmust understand and answer simple, direct questions and demonstrate alimited knowledge as to polite phrases, everyday and standardised expres-sions. In order to pass, the applicant must have at least 28 correct answers.The level of the Danish language test is A1-minus corresponding to the testfollowing Module 1 at DC1 and DC2.29Based on the rulings af the European Court of Justice (on how to interpret the 1963 as-sociation agreement between the EU and Turkey) in the case of T. Sahin (17 September2009, C-242/06) and the Commission v. The Netherlands (29 April 2010, C-92/07), theDanish immigration authorities have concluded that these group of foreigners cannotbe required to take the immigration test (or to pay the test fee).Thus, foreigners from countries such as the US, Australia, Japan and North Korea arealso covered (unlike in the Netherlands, see Eva Ersbøll 2010, p. 129-130).

30

20

DENMARK

The knowledge test comprises 30 questions and in order to pass, the ap-plicant must have at least 21 correct answers. The level will be higher thanA1-minus. Vocabulary will be kept within the scope of the preparatory mate-rial. The intention is that immigrants must be familiar with Danish norms,values and fundamental rights, including democratic principles, individualfreedom, personal integrity, gender equality, freedom of religion and free-dom of speech; furthermore immigrants must be familiar with certain morepractical facts such as the prohibition of female circumcision, forced mar-riages and parental responsibility for their children, education, health, work,etc.No preparatory courses for the immigration test are offered. However,for the purpose of the test, a preparatory package is prepared. The most cen-tral part of the package is an educational film entitled, ‘Living in Denmark’.31The aim of the film is to give the participants a realistic general picture ofDenmark and daily life in Denmark. Thus, the film communicates both factsand values with a view to adapting the expectations of the immigrants toDanish reality. According to the Ministry of Integration, the basic message ofthe film will be that prospects in Denmark are good for those who are willingto make an effort and take responsibility for their life in Denmark.The film is supposed to provide answers to the test questions about Dan-ish society. It is approximately 90 minutes long and consists of 17 chapters. Itis produced in Danish and recorded in 18 different foreign languages (noreading abilities are required). The film is not supposed to include languagelessons since the immigrants themselves are responsible for their preparationfor the language test. However, some expressions from the language testmay be present in the film.Apart from the film, the preparatory package contains a recorded vo-cabulary list, 100 pictures from the film with information about Denmarkand Danish society, two samples of the language test, test instructions, etc.All material is available in a spoken version - dubbed into 18 foreign lan-guages.32The test will be administered by a computer based test system playingthe questions and recording the (oral) answers on a sound track. For eachquestion, the computer shows a relevant picture from the educational film;likewise it shows a picture for four out of every five language test exercises.The societal knowledge test and the language test are conducted in Danish

31

32

‘Livet i Danmark’, see http://www.nyidanmark.dk/da-dk/Integration/integration_af_ny-ankomne/indvandringsproven/Et+liv+i+Danmark+–+undervisningsfilm+til+indvan-dringsprøven.htm.Each image is accompanied by important information. The information will be readloud in Danish and the language the applicant chose when inserting a DVD. All wordsused in the knowledfge test are included.

21

DENMARK

and all questions must be answered in Danish. The tests will be evaluated byexternal examiners.A fee of 3000 DKK (about 300 euro) has to be paid to take the test. Thepreparatory packet costs 50 DKK (about 7 euro) plus shipping and admini-stration fees (about 150 DKK or 20 euro).As already mentioned, the test must be taken in Denmark after the appli-cant has received recognition in advance of his or her application for familyreunification. Applicants subjected to a visa requirement will be granted aspecial short-stay visa, valid for 28 days from the date of issue, with a view toenter Denmark. Before the entry visa expires, the applicant must submitspecified documentation to the Ministry of Integration in order to be granteda right to ‘procedural stay’ in Denmark for three months in order to pass theimmigration test. While staying in Denmark, the applicant may in principletake a language course at his or her own expense. However, in practice thismay give rise to difficulties, see also below under 2.2.33As a rule, foreignerscoming to Denmark in order to pass the test must do so within the first two-and-a -half months (75 days) of their arrival, and foreigners applying forfamily reunification in Denmark must do so within two and a half months af-ter the date of a letter from the Ministry of Integration informing them thatthey need to take the test; if this time limit is exceeded, there may not beenough time to evaluate the test within the three-month time limit. Duringthe three-month period the test may be re-taken, but the fee of about EUR400 must also be paid again. If an applicant has not passed the test within thethree-month time limit, family reunification will be refused and a date fordeparture will be fixed.Per year, 1500 – 2000 foreigners are expected to take the test; the estimateis based on the present number of resident permits issued to reunifiedspouses/partners and religious preachers.

2.2

Purpose of the Test

The introduction of the immigration test has received relatively little atten-tion in the Danish media. During the debate in Parliament, it was stressedthat the immigration test was not devised by the government; it was, alleg-edly, successfully implemented in the Netherlands – and, according to in-formation received, not accused of violations of international treaty obliga-tions.

33

The Ministry of Integration inform that it is the applicant’s own responsibility to learnDanish. Possibly with help from the spouse/partner, by taking courses in the country ofresidence, by buying language courses in the form of books or CDs, or by taling onlinelanguage courses.

22

DENMARK

Before the legislative work, during a consultation procedure, a number ofNGOs and other organisations and institutions criticised the test for beingexclusive, especially taking into consideration the lack of educational offersand the high fee, which as a whole, could make it difficult, if not impossible,to pass for poor and/or uneducated applicants. In order to solve some of thealleged problems, it was suggested to be made possible for migrants to takethe knowledge test in their own language.Among the opposition parties in Parliament, the Social Democrats sup-ported the idea of introducing an immigration test provided that all appli-cants regardless of their educational and financial backgrounds were able topass it. Members of the party suggested that more time should be allotted forstaying in Denmark while preparing for the test; furthermore, they asked formore information about the Dutch experiences.The Minister for Integration has from the very beginning stressed thatthe purpose of the test is not to limit the number of family reunifications –nor is it to keep foreigners out of Denmark; no marked decrease in the num-ber of applications is expected. During the debate in Parliament in 2010 theMinister made it quite clear that the test would be adjusted in such a waythat all ‘can work it out’.34She emphasised that it is not about ‘integration’,but may regarded as a ‘taster’, making it possible for applicants to documenttheir interest in being integrated and becoming familiar with Danish norms.Based on the test, some migrants might change their minds about staying inDenmark - having discovered ‘what it is all about’ (learning about Danishsexual morality, etc.). The test is supposed to send a signal to newcomers thatintegration is also about individuals contributing actively and engaging intheir own integration; likewise, the test aims to give applicants some realisticexpectations of their life in Denmark and the possibilities, requirements, ob-ligations, etc. they will encounter.The Minister for Integration argued against the possibility of allowingimmigrants to take the test in their own language. As for the idea of offeringpreparatory language courses, she stressed that a central element of the im-migration test is that it is up to the individual to prepare for the test and ap-plicants may start preparing themselves for the test in their country of origin.In response to a question, she stated that if all applicants were to be offeredDanish language education at Module 1 at the Danish language courses – themodule (at DC1 and DC2) expected to lead to Danish language skills at levelA1 minus – the cost would be between 32.7 and 44.3 million DKK (EUR 4.4 –6 million euros), and probably only applicants with a good educational back-ground in their country of origin would be able to complete the modulewithin the 75 days allocated for passing the immigration test.

34

Oral test and preparatory material that do not imply writing or reading abilities.

23

DENMARK

2.3 Effects of the testAt present, it too early to forecast the effects of the immigration test. How-ever, within the Ministry of Integration, an evaluation of the test is plannedfor about one year after its entering into force. The evaluation is to be pre-sented in Parliament.

24

DENMARK

Chapter 3: Integration Test in Denmark as a Condition for aPermanent Residence Permit etc.3.1The Test

3.1.1 Integration Test RequirementsThe integration test requirements in force since 2 June 2010 were, as men-tioned above in section 1.3.1, adopted on 25 May 2010 and have not yet had ameasurable effect; all the applicants interviewed in connection with this re-search project have so far been subjected to other requirements, dependingon when they applied for a residence permit in Denmark. For the purposes ofthis research, it is therefore appropriate to describe the requirements forpermanent residence adopted over the last ten years.Until 1999, access to secure status was regulated indirectly by the AliensAct’s imposition of a five-year time limit for withdrawal of a residence per-mit.35However, in 1998, by an amendment to the Aliens Act, this arrange-ment was repealed and permanent residence was made conditional upon in-tegration requirements; these requirements have become strict. The integra-tion conditions (which, due to transitional rules, were in force until June2010) will be mentioned below. It should be noted that the respondents inthis project normally refer to these earlier rules in force when the interviewswere conducted.

3.1.2 Requirements 1999-2002The 1998 Aliens Act provided for the granting of a permanent residencepermit to a foreigner holding a residence permit issued with a view to per-manent residence if that person had lived in Denmark for more than 3 years(section 11(3)), provided that a number of supplementary conditions werefulfilled. These conditions were introduced in order to emphasise that a for-eigner wishing to stay in Denmark on a permanent basis would be expectedto make an effort to learn the Danish language and adapt to the Danish soci-ety.36Thus, at that time, in order to qualify for a permanent residence permit,a foreigner had to complete an integration programme (or a comparablecourse).37Furthermore, the applicant was not allowed to have public debt353637Consolidation Act no. 557 of 30 July 1998, section 11(2):Jens Vedsted-Hansen: Tidsbegrænsning og forlængelse af opholdstilladelser, in Lone BChristensen et al.,Udlændingeret,p. 531 ff.Only active participation in the introduction programme was required.

25

DENMARK

amounting to more than 50,000 DKK (about 6,760 euros) and convictions forcrimes would result in waiting periods (section 11(5)).38

3.1.3 Requirements 2002–2006In 2002, the residence requirement for being granted a permanent residencepermit was raised from 3 to 7 years (section 1(3)). Furthermore – in additionto completing an integration course (section11 (7) (1)) – the applicant had topass a test in the Danish language (section 11 (7) (2)).39Moreover, seriouscrimes (prison sentences of two years or more or other criminal penalties forserious crimes) would prevent the applicant from acquiring a permanentresidence permit (section11 (5),40as would any overdue public debt (section11(7) (3)).In 2003, with an amendment to the Aliens Act, the requirement of 7years’ residence as a condition for being issued a permanent residence per-mit was modified. The government had suggested, in its integration proposalof 5 March 2002 that foreigners who had made a successful effort to integrateinto Danish society (including self-supporting foreigners), should have thepossibility of acquiring a permanent residence permit earlier than wouldnormally be the case. Thus, with the amendment, in principle it became pos-sible for ‘well integrated foreigners’ to acquire a permanent residence permitafter 5 or 3 years; the possibilities depended on the foreigner’s integrationlevel (firm connection to the labour market, self-support for the last threeyears and close ties with Danish society through, for instance through asso-ciation or political activity or long-cycle higher education) (section 11(4 and5)).41After the government had entered into an integration agreement with theDanish People’s Party and the Social Democrats on 17 June 2005, with a viewto implementing its new integration plan, ‘A New Chance for Everybody’,the Integration Act and the Aliens Act were changed again. Apart from in-troducing ‘integration contracts’ lasting until the issue of a permanent resi-dence permit, together with declarations on integration and active citizen-

3839

40

41

See Consolidation Act no. 73 of 2 February 1999.The test requirement was not part of the Bill, as presented by the Minister for Integra-tion, but inserted during the debate in the Parliamentary Committee – proposed by theDanish People’s Party and supported by the Social Democrats who, however, empha-sized that it should not be a vicious circle, meaning that there should not be increas-ingly ‘high requirements in future’, see www.ft.dk, L 152 second reading 23.5.2002.Other (suspended or unsuspended) sentences of imprisonment would still postpone thedate on which the applicant were eligible for a permanent residence permit (section11(6)).Act 425 of 10 June 2003.

26

DENMARK

ship, etc., the purpose was again to tighten the conditions for obtaining apermanent residence permit. Thus, a new requirement for acquiring a per-manent residence permit was that a foreigner – in addition to completing theintroductory programme and passing a test in the Danish language – com-plete the activities (regarding job plan, etc.), which (according to the Act onan Active Labour Market Policy) were laid down in the integration contract(section 11(9)(2)). Furthermore, in order to obtain a permanent residencepermit, the foreigner (still) has to sign the integration contract and the decla-ration on integration and active citizenship (section 11 c).42

3.1.4 Requirements 2006–2010On 20 June 2006, the government entered into a new agreement with theDanish People’s Party on future immigration. On the same day, a broaderwelfare agreement was secured and the immigration agreement was an ex-tension of this agreement; the challenges to be met in order to secure futurewelfare and cohesion included the employment of immigrants and immi-grants’ descendents. Employment was seen as a better way to integrate. Itwas considered important for foreigners to be met with a clear signal as towhat was expected of them in Denmark. Immigration policy should contrib-ute towards improving Denmark’s position in the competition for highlyqualified international labour. Increasing highly qualified labour wouldstrengthen welfare and production and enhance the employment possibili-ties for persons with limited education. In the agreement, it was decided thatthe existing job card scheme would be extended and a green card scheme es-tablished; furthermore an ‘integration examination’ would be required as acondition for the issue of a permanent residence permit.In November 2006 the Minister for Integration presented a Bill amendingthe Aliens Act and the Act on Active Social Policy, providing for an integra-tion examination, a green card scheme, residence permits for foreigners withan annual salary of 450,000 DKK (60,000 euros) (the pay limit scheme) andresidence permits for foreigners with special qualifications (the positivelist).43The Act was adopted in April 2007. Thus, according to the amendedAliens Act, it was made a condition for the issue of a permanent residencepermit that the applicant pass a test in the Danish language at level D2E(level B1) or have passed a test in the Danish language at level D1E (level A2)together with a test in English at level B1 (section 11(8 and 9)). Moreover, the42See Act no. 243 of 27 March 2006; among the additional conditions for permanent resi-dence were still that the applicant must not have overdue public debt and not havebeen sentenced to two or more years’ imprisonment or other criminal sanctions for seri-ous crimes.Act no. 379 of 25 April 2007.

43

27

DENMARK

applicant was required to have been in ordinary full-time employment inDenmark for at least two years and six months over the past seven years (sec-tion 11(8) (IV). Together, these two new requirements (the language and theemployment requirement) were labelled ‘the integration examination’.

3.1.5 Requirements 2010 onwardsIn 2010, a new agreement regarding access to permanent residence and otherissues was entered into by the government and the Danish People’s Party (15March 2010). One of its aims was to make it possible for ‘well-integrated im-migrants’ to acquire a permanent residence permit after just 4 years (insteadof 7) and, on the other hand to make it more difficult for ‘poorly integratedimmigrants’ to acquire this status. The Aliens Act was amended accordinglywith support from members of the Liberal, Conservative and Danish Peo-ple’s Parties.44The members of the other parties voted against the changes.The spokespersons for the Social Democrats, the Socialist People’s Party, theSocial Liberals and the Red-Green Alliance opposed the inflexibility of thesystem, which would make it impossible for some immigrants to obtain apermanent residence permit. The viewpoints of the Social Democrats and theSocialist People’s Party, who in general have accepted the government’s‘firm and fair aliens policy’ with a view to form a new government after thenext election, was challenged by the governing parties and the Danish Peo-ple’s Party warning against the possibility that the ‘firm and fair aliens pol-icy’ would not be continued if the opposition obtained a majority in parlia-ment after an election.45Following the reform of the rules on access to permanent residence, for-eigners applying for a permanent residence permit as of 26 March 2010 musthave attained the age of 18 and obtained at least 100 points according to theAliens Act, section 11, paragraphs 4-6 (70 points must be obtained accordingto paragraph 4, 15 points according to paragraph 5 and 15 points accordingto paragraph 6).Firstly, applicants for permanent residence must fulfil eight essentialconditions in order to obtain 70 points, cf. section 11(4). They must:1) have resided legally in Denmark for at least 4 years;2) not have been sentenced to imprisonment for 18 month or more;463) not have been sentenced to 60 days’ imprisonment or more for violationof Parts 12 and 13 of the Criminal Code (crimes against the Danish state);4) not have outstanding debt to the public authorities, unless a defermenthas been granted and the debt is below 100,000 DKK (13,500 euros);444546Act no. 572 of 31 May 2010.Negotiations of 20 May 2010.Imprisonment for a shorter period will result in waiting periods up to 12 years.

28

DENMARK

5) not have received welfare assistance (Act on Active Social Policy or Inte-gration Act) within the three years preceding submission of the applica-tion for a permanent residence permit;6) have signed a declaration on integration and active citizenship;7) have passed the D2E (level B1) or a Danish language test at an equivalentor higher level;8) have held ordinary full- time employment in Denmark for at least 2.5years out of the last 3 years before submitting the application for a per-manent residence permit.Moreover, the applicants must achieve an extra 30 points by making an extraeffort with a view to integration through9) ‘active citizenship’ and10) employment or Danish language proficiency or education.The ‘active citizenship’ requirement (that counts for 15 points (cf. section11(5)) is met if the applicantsa) pass a special ‘active citizenship examination’,orb) demonstrate active citizenship in Denmark through at least one year’sparticipation as an active member of boards, organisations etc.The ‘supplementary conditions relevant to integration’(that count for 15points (cf. section 11(6)) are met if the applicants meet one of the followingintegration-related requirements:a) have held ordinary full -time employment in Denmark for at least 4 yearsout of the last 4,5 years before submitting the application for permanentresidence and still be in employment at the time when the permanentresidence permit is granted, orb) have completed one of the following programmes at a Danish educa-tional institution: a higher education programme, a professional bache-lor’s degree, business degree or vocational upper secondary education;orc) have passed D3E or a Danish language test at an equivalent level (B2) orhigher.

3.1.6 Exemption PossibilitiesForeigners who receive an old-age pension are exempt from the require-ments of 1) achieving 15 points according to section 11(6) (supplementaryconditions relevant to integration), and 2) having worked in Denmark for atleast 2 years and 6 months out of the past 3 years before submitting the ap-plication for a permanent residence permit (cf. section 11(4)(8)). The sameapplies to 18 year-old foreigners who apply for a permanent residence per-

29

DENMARK

mit before turning 19, but only in so far as they have been in school or work-ing full-time since they completed the DanishFolkeskole(municipal primaryand lower-secondary school) (cf. section 11 (10)).Furthermore, foreigners with strong ties to Denmark may be exemptedfrom the conditions of section 11 (4) (1, 5, 6 and 8) as well as 11 (5 and 6).Foreigners ‘with strong ties to Denmark’ are defined as foreigners belongingto the Danish minority in South Schleswig, former Danish citizens, foreignerswith Danish parents and foreigners who are Argentinean citizens with Dan-ish parents or grandparents (cf. section 11 (11)).Finally, exemption is possible for foreigners who cannot fulfil one ormore of the requirements of section 11 (4) (4-8) and 11 (5-6) ‘if the demandscannot be made due to Denmark’s international obligations, including theUN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities’. Guidelines con-cerning whom to exempt according to this new, very broadly formulatedrule are lacking and much is left to the discretion of civil servants and judges,which has been criticised by many of the institutions and organisations in-volved.

3.1.7 Interim ProvisionsUntil the adoption of the 2010 requirements, interim provisions ensured thatimmigrants who had applied for a residence permit under one of the Actspreviously in force and who fulfilled the integration conditions according tothe Act in force with the exception of the residence requirement (7 years resi-dence in Denmark) would not face new requirements for which they had notprepared. Thus, by way of example, applicants who had applied for a resi-dence permit between 1 January 1999 and 27 February 2002 and who hadcompleted an introductory programme before 29 November 2006 were notrequired to take a language test, and applicants who had applied for a resi-dence permit between 28 February 2002 and 30 June 2006 and had completedan introductory programme and passed a language test before 29 November2006 were not faced with the requirement of having to pass a Danish lan-guage test at level B1 (if for instance they had enrolled in DC1, D1E (level A2)would suffice). However, as of 26 March 2010, all applicants now need to ful-fil the new stringent requirements for permanent residence and run the riskthat they cannot acquire a permanent residence permit (any more), irrespec-tive of their former legitimate expectations of having qualified for permanentresidence.

30

DENMARK

3.1.8 FeesThe Danish language courses are free of charge. Until the adoption of the2010 reform, the local council was allowed to charge a fee per module fromself-supporting foreigners who were not covered by the Integration Act (forinstance, foreigners covered by the EU right of free movement, etc., labourmigrants, specialists, au pairs and exchange students). This possibility hasbeen repealed as of 1 August 2010 as part of the government’s de-bureaucratisation plan. However, in relation to students who want to registerfor a languageexaminationand who have not followed a language course, itis still possible to charge a fee of 1000 DKK (about 130 euros).Furthermore, a cost-based fee will be charged for the ‘active citizenshiptest’. The test is supposed to be introduced in mid-2011 and to be similar tothe naturalisation test.47However, the subject level will be a little below thelevel of the naturalisation test and the number of questions will be only 15 –10 of which must be answered correctly. Thus, there is reason to believe thatthe cost-based fee will not exceed the naturalisation test fee (660 DKK orabout 90 euros).

3.2

Purpose

According to the preparatory work for the latest reform of the Aliens Act, thepurpose of the amendments is to make it possible for ‘well integrated immi-grants’ to acquire a permanent residence permit earlier than was previouslythe case, i.e. after 4 years’ residence instead of (previously) 7 years.48More-over, the reform is intended to send a signal regarding what Denmark ex-pects from its new co-citizens. The message is that foreigners have a personalresponsibility for their integration and active citizenship and that foreignerswishing to integrate in Denmark and demonstrate goodwill as regards activecontribution and respect for Danish culture and democratic values can be-come part of Danish society and obtain a permanent residence permit. On thecontrary, foreigners who do not ‘demonstrate goodwill to integrate’ will beexcluded from acquiring a permanent residence permit. The focus hasmoved to ‘the result of the will to integrate’.The new strict and inflexible integration requirements give some causefor concern. After the Bill was presented in Parliament, the organisations andinstitutions consulted, etc., warned against repeated changes of the alien leg-islation and the uncertainty this created among immigrants. Furthermore,many organisations, etc., warned that many immigrants would not be able to4748See below, however, in section 4.1.This possibility did already exist, but was not often used, cf. above under 3.1.3. This hasnot been extensively discussed in the recent debate in Denmark.

31

DENMARK

fulfil the requirement concerning on full-time employment combined withthe educational requirements – regardless of their goodwill. In particular,unskilled workers may find it hard to allocate the necessary time to studying,and immigrants undergoing of training will have to wait for a number ofyears before they can (hopefully) fulfil the requirement of full-time employ-ment. Vulnerable immigrants, among others traumatised refugees, will faceeven bigger problems than before. They may be exempted from fulfillingsome of the requirements, but, as already mentioned, only in so far as re-quired by ‘Denmark’s international obligations, including the UN Conven-tion on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities’ (cf. section 11, paragraph 12) –and it is up to the applicants to prove that they have a disability that entitlesthem to exemption.The media dealt with the criticism; for instance, a debate between theMinister for Integration and the Director of the Danish Institute for HumanRights (DIHR) was brought into focus. The DIHR had criticised the strictercriteria for permanent residence as being exclusive and unjustifiable with aview to integration. The Minister for Integration stated that she was inter-ested in advice regarding possible violations of Denmark’s human rights ob-ligation, but characterised some of the criticisms raised concerning whetherthe criteria applied were ‘justifiable’ and ‘promoting integration’’ as ‘ entirelyinappropriate political viewpoints’.

3.3

Effect

3.3.1 Analysis of StatisticsVirtually no literature or public statistics exist on the effects of the tests.However, the Ministry for Integration has, upon request, conducted a statis-tical survey of permits and refusals of permanent residence from 2003 – 2009.The survey only covers applicants with a residence permit issued for eitherasylum or family reunification. It has not been possible to perform a similarsurvey for applicants with a residence permit issued for work or study dueto the fact that the ‘aliens register’ is established as a journal and a case- han-dling system – rather than as a genuine statistical database. Since there is nocurrent validation, figures regarding access to permanent residence must beinterpreted cautiously.

32

DENMARK

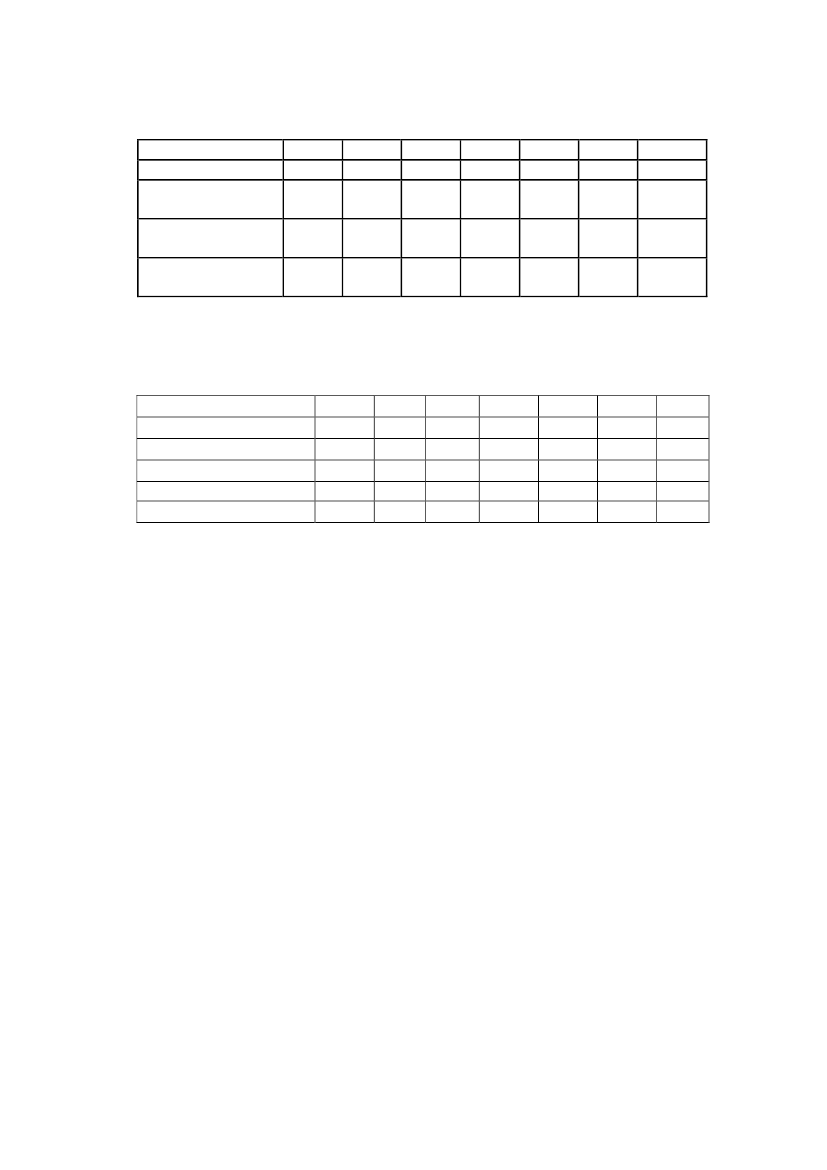

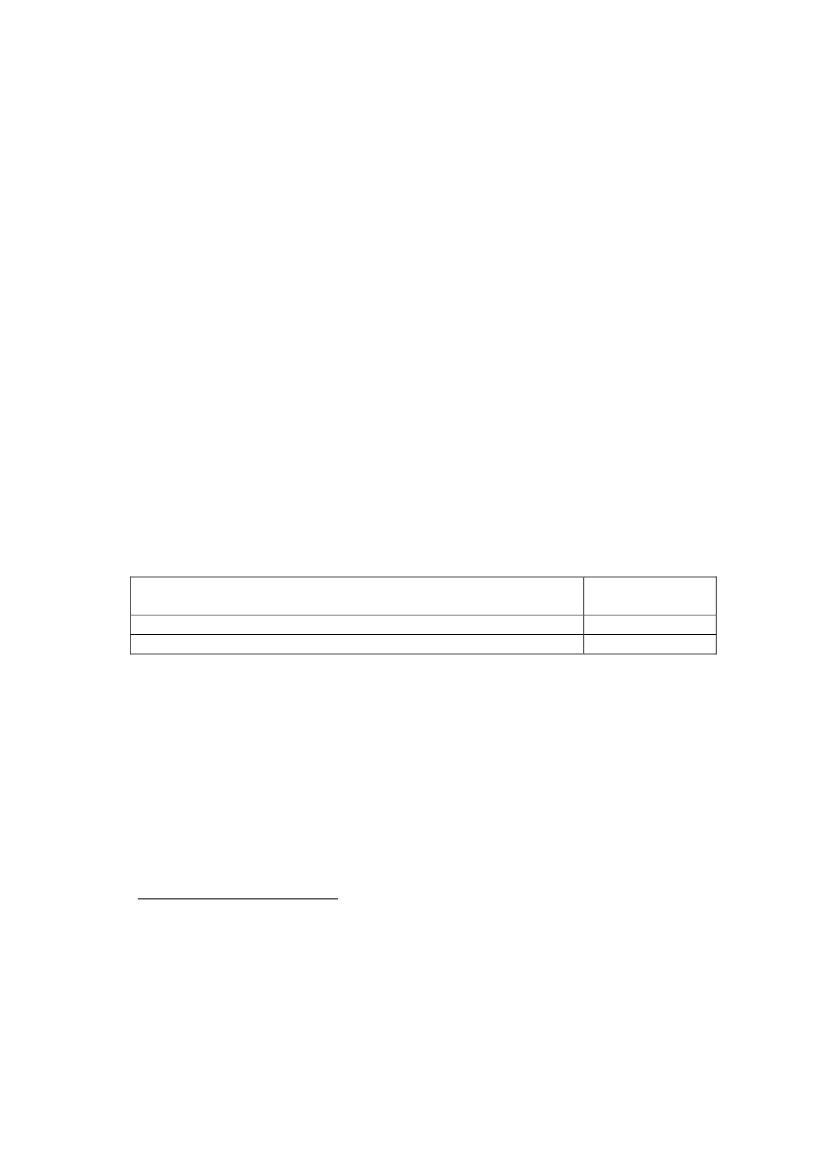

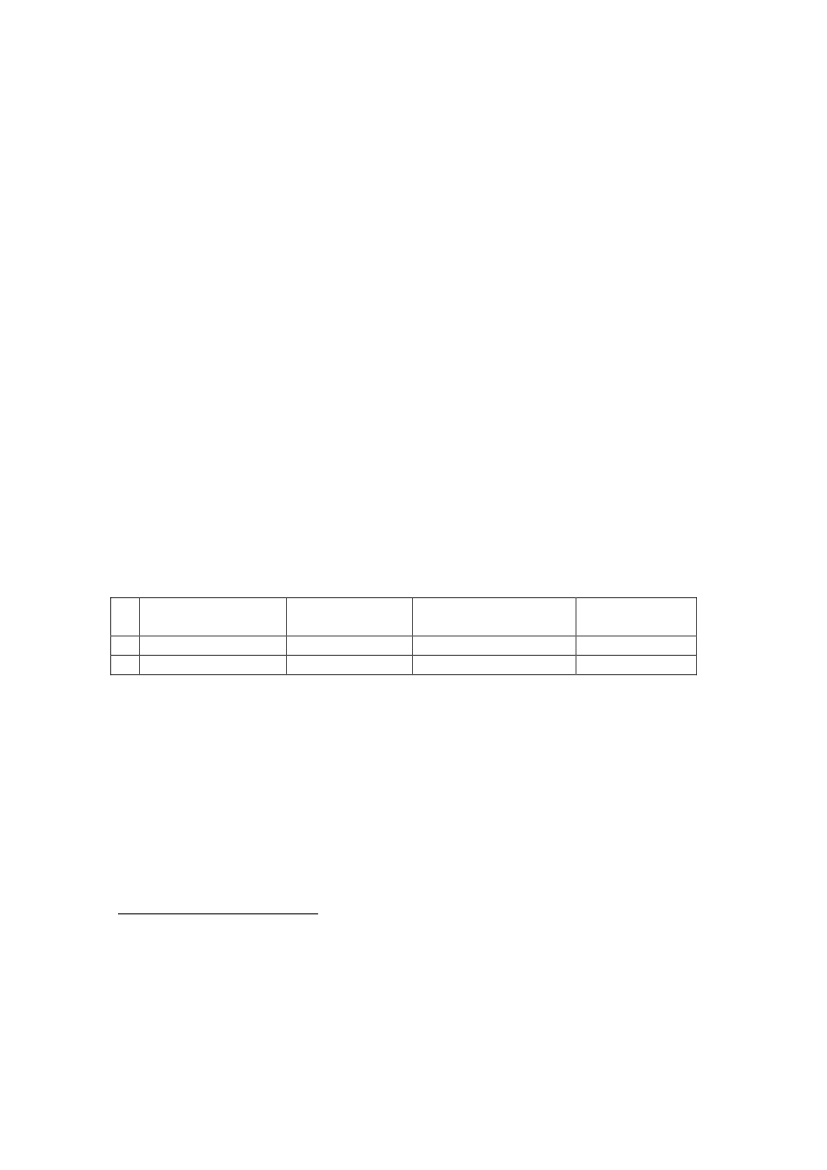

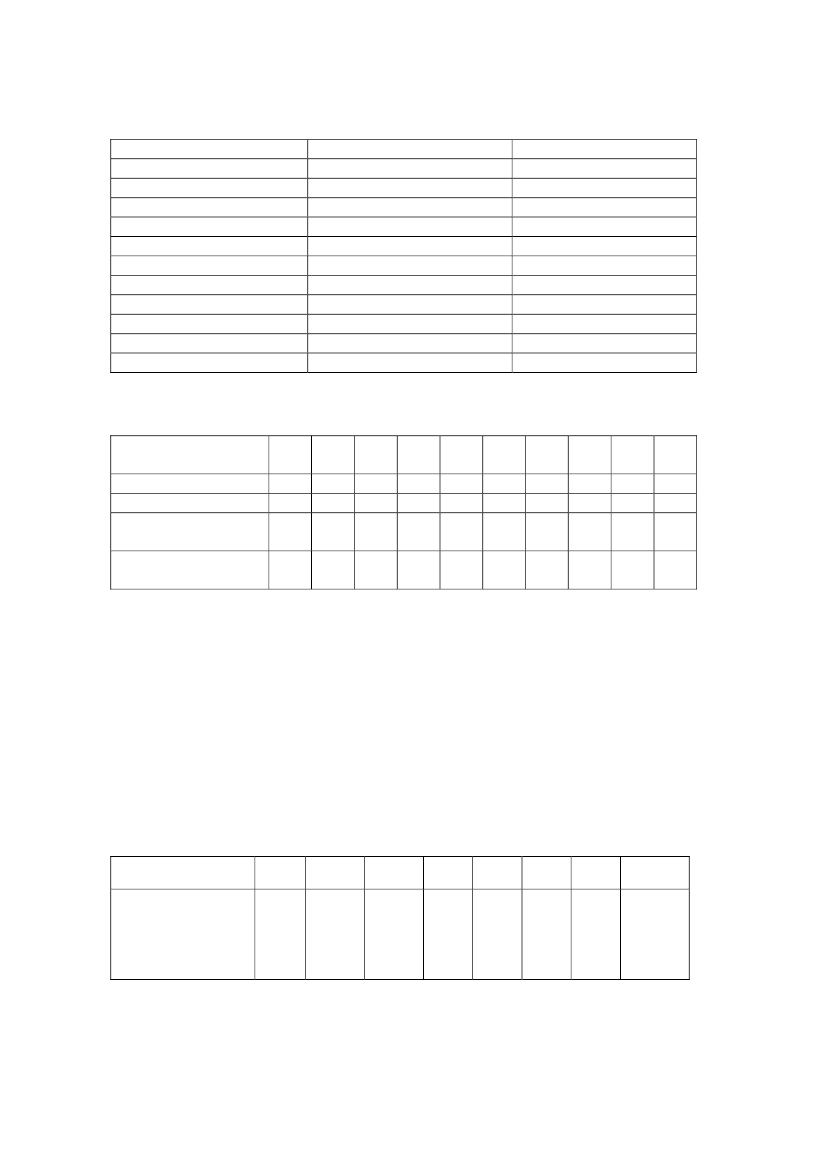

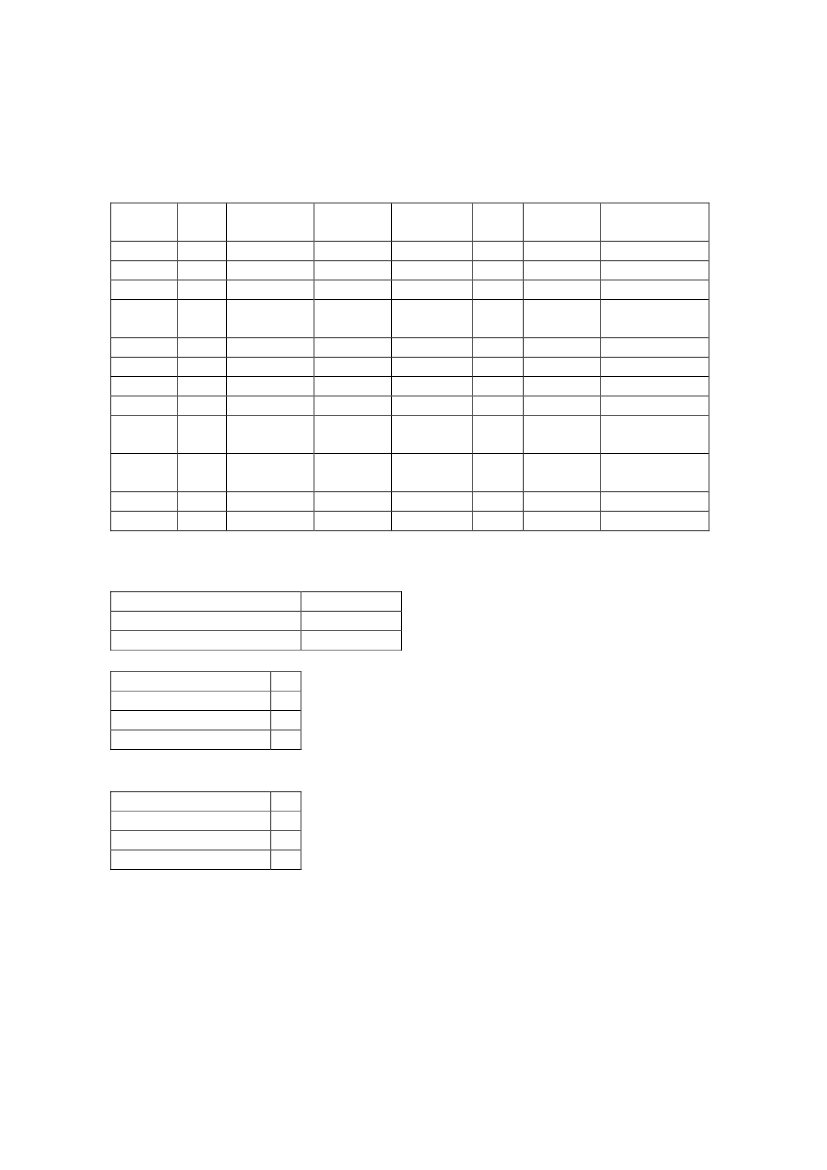

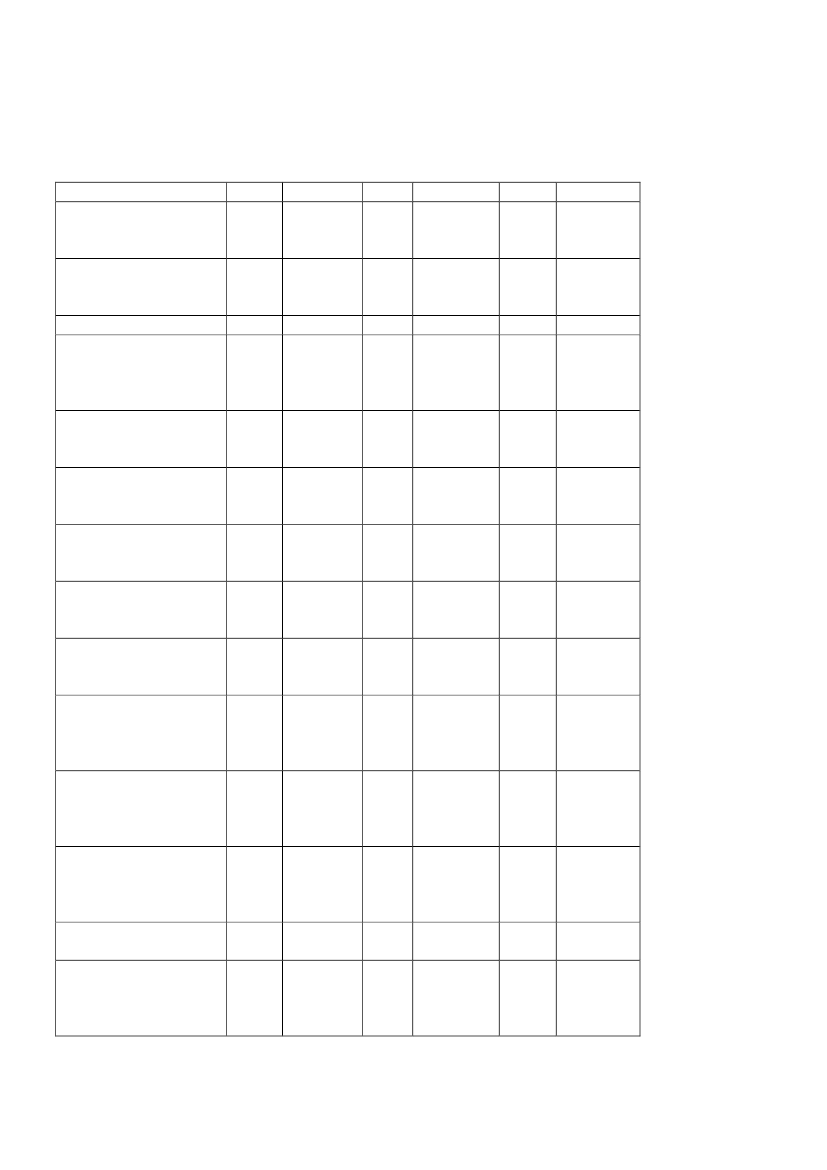

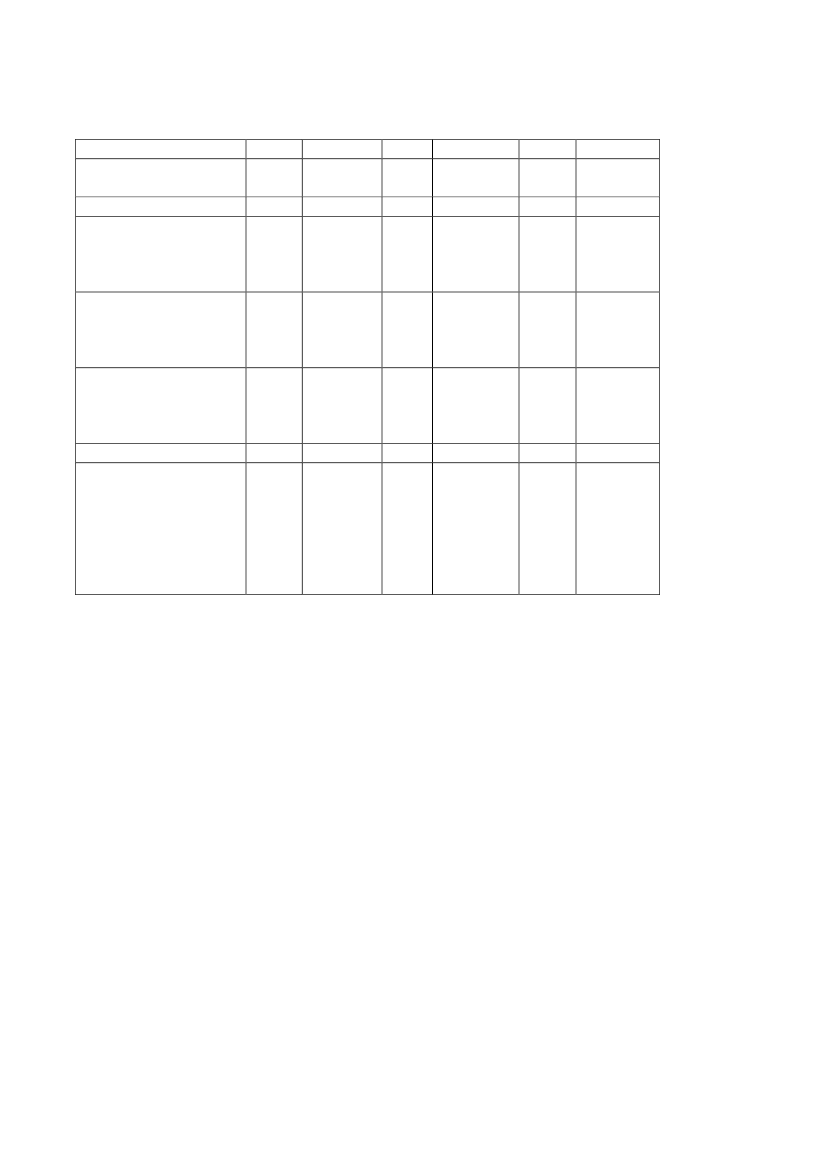

Table 1: Applications for permanent residence granted and denied, 2003–2009*Refugees – refusalRefugees - permis-sionFamily reunification2066196818121862896– refusalsFamily reunification56285857463921151341- permissionsSource: Aliens Service.*2009 figures are frozen, preliminary figures assessed 9 January 2010.20032103732200434848812005448452220063761526200770447200882971315202345200949441812922308

Table 2: Applications for permanent residence granted and denied, 2003–2009; totalnumbers and percentage of refusals.*2003Total number of decisionsTotal number of refusalsTotal number of permitsPercentage of refusals1163622769360200413054231610738200511421226091612006587922383641200727549661788200854072349305843.4200945121786272639.6

19.617.719.838.135.1Source: IMR calculation based on statistics from the Aliens Service.*2009 figures are frozen, preliminary figures assessed 9 January 2010.

The statistics show that thenumber of applicationsfor permanent residence hasdropped dramatically from 2006 (by more than half). This development maybe seen in the light of the fact that immigrants who were issued a residencepermit before 27 February 2002 were subject to the rules applicable until thenand, thus, when applying for a permanent residence permit they only had tofulfil a residence requirement of 3 years – while immigrants who have beenissued a residence permit since 28 February 2002 have to fulfil a 7-year resi-dence requirement for permanent residence.Moreover, the statistics show that thenumber of permanent residence per-mits issuedhas dropped even more since 2006. Information on the reasonsgiven for the refusals is not available, but an obvious conclusion may be thatthe lower number of permits has to do with the introduction of the languagetest requirement and the ‘integration examination’ requirement. While appli-cants for permanent residence who had been issued their first residencepermit before 28 February 2002 did not have to fulfil a language test re-quirement (they only needed to have completed their introductory pro-gramme before 29 November 2006), applicants who had been issued theirfirst residence permit during the period 28 February 2002 – 1 April 2006 wererequired to pass a language examination for the language course in whichthey had enrolled (D1E, D2E or D3E). Only applicants who had not com-pleted an introduction programme and/or passed a language examinationbefore 29 November 2006 and applicants who had been issued their first

33

DENMARK

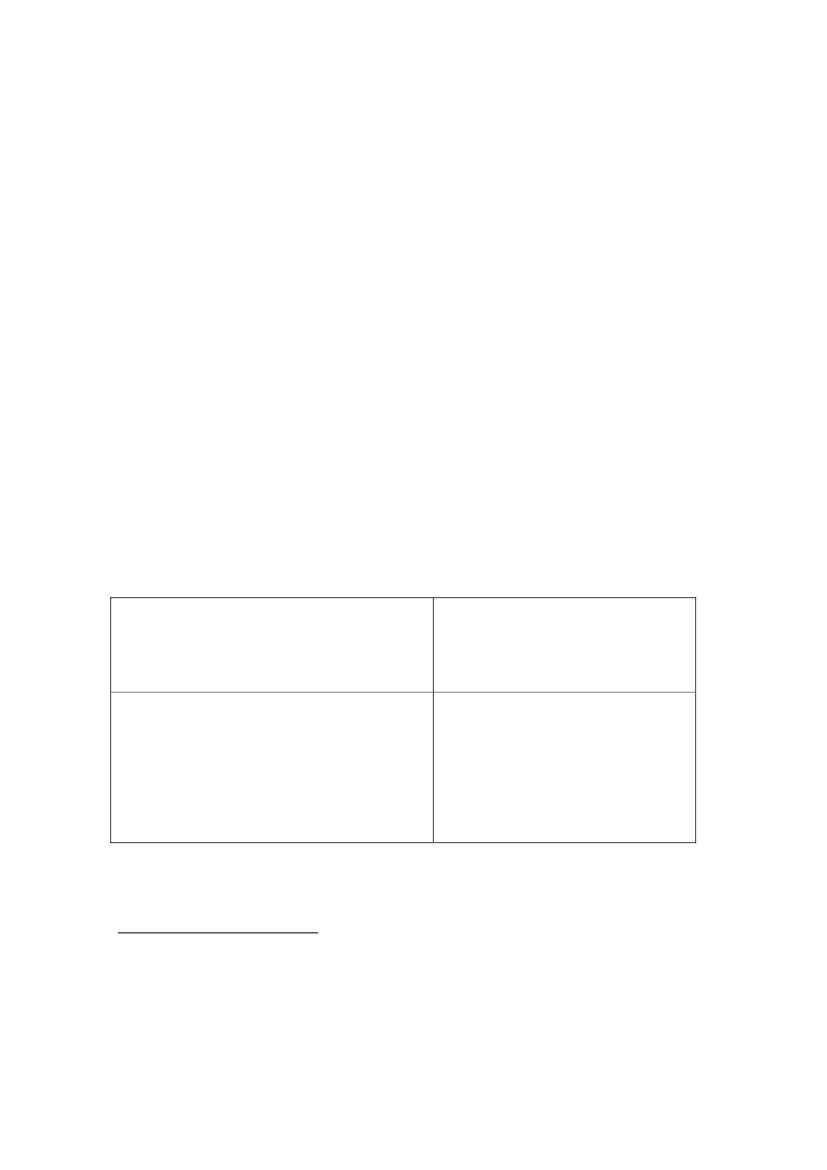

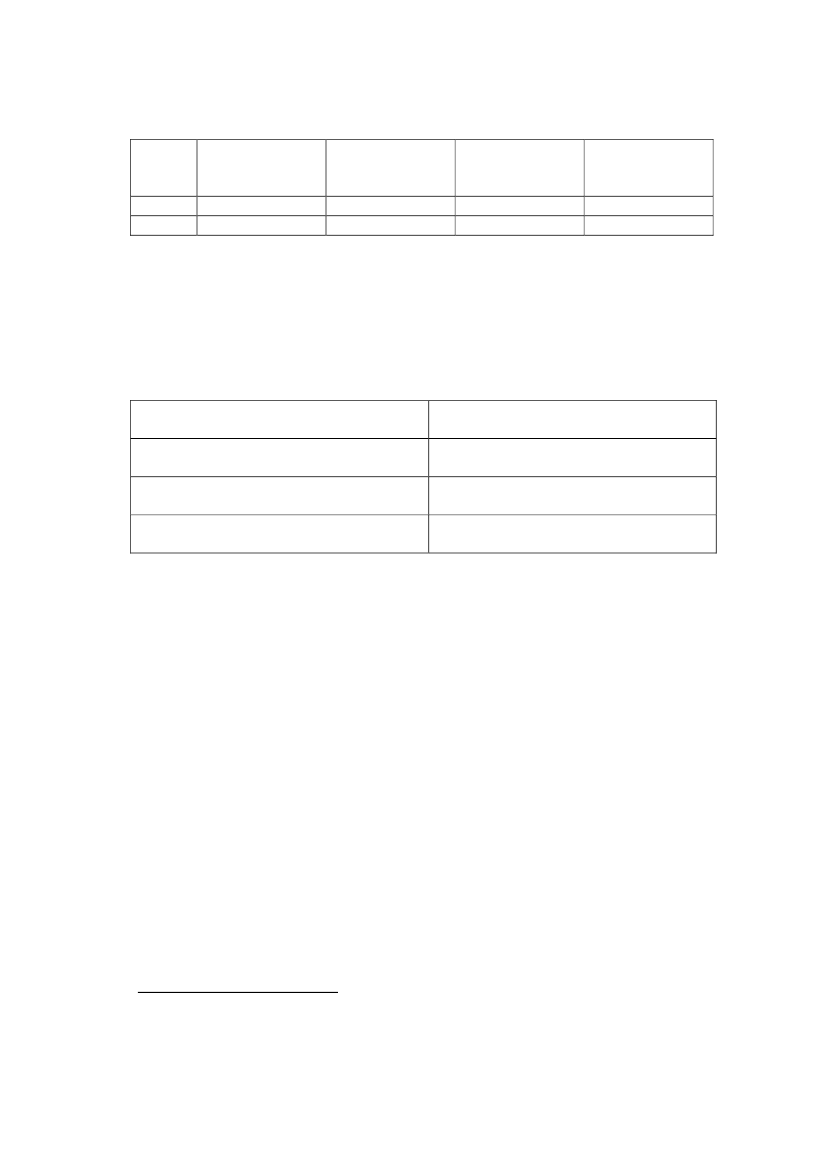

residence permit after 1 April 2006 had to fulfil the ‘integration examinationrequirement’ (D2E + full-time employment for 2.5 years out of last 7 years).Yet, due to the general residence requirement of 7 years, the full effects of theintegration examination had not been seen (or evaluated) before the new andeven more restrictive requirements were introduced in 2010.Developments for refugees and foreigners reunited with families havenot been the same; see Table 3.Table 3: Applications for permanent residence granted and denied, 2003–2009; totalnumbers and percentage of refusals for refugees and family reunified immigrants*RefugeesTotal number ofdecisionsPercentage of refusals200339425.3200452296.7200549709.02006190219.8200751713.52008154253.8200991254.2

Migrants reunited withfamiliesTotal number of deci-sions76947825645139772237Percentage of refusals26.925.228.146.840.1Source: IMR calculation based on statistics from the Aliens Service.*2009 figures are frozen, preliminary figures assessed 9 January 2010.

386539.3

360035.9

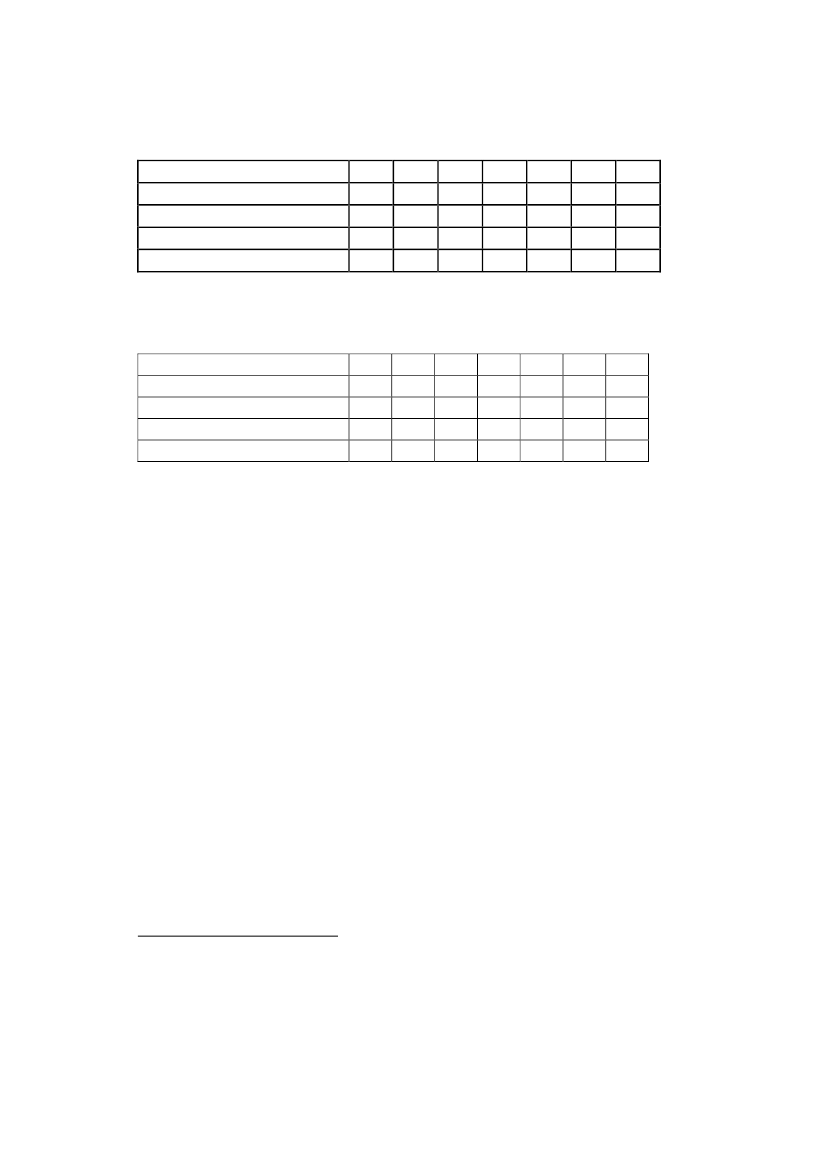

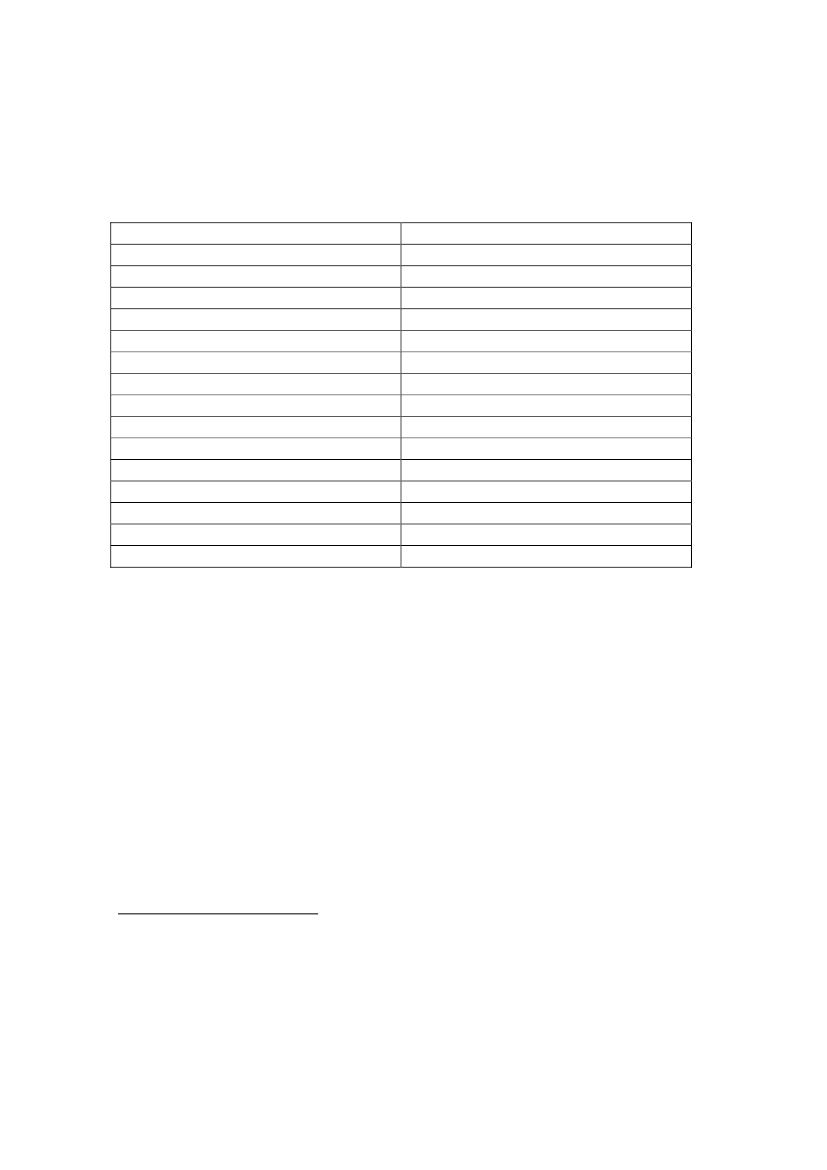

Refugees account for the majority of the refusals and have, in general, beenmost affected by the changes. Thus, until 2006 less than 10 per cent of therefugees’ applications for permanent residence were refused. In 2006 the to-tal number of decisions fell to less than half, and the percentage of refusalsmore than doubled (from 9 per cent to about 20 per cent). However, the effectof the changes is most dramatic in 2008 and 2009, when more than half of allapplications were turned down.Tables 4 and 5 show that when the statistics are broken down by agegroup, a considerable number of (successful) applications originate fromchildren and 18-year-old applicants. However, as of 26 March 2010, accord-ing to the 2010 amendments, children can not longer apply for a permanentresidence permit and by the age of 18, they must be continuing their studiesor working full-time since they completed primary and lower secondaryschool in order to be exempt from the requirement regarding having beenemployed full-time employed for at least 2.5 years out of the last 3 years.Thus, due to these constraints, it is very likely that from now on the numberof permanent residence permits will decline further.

34

DENMARK

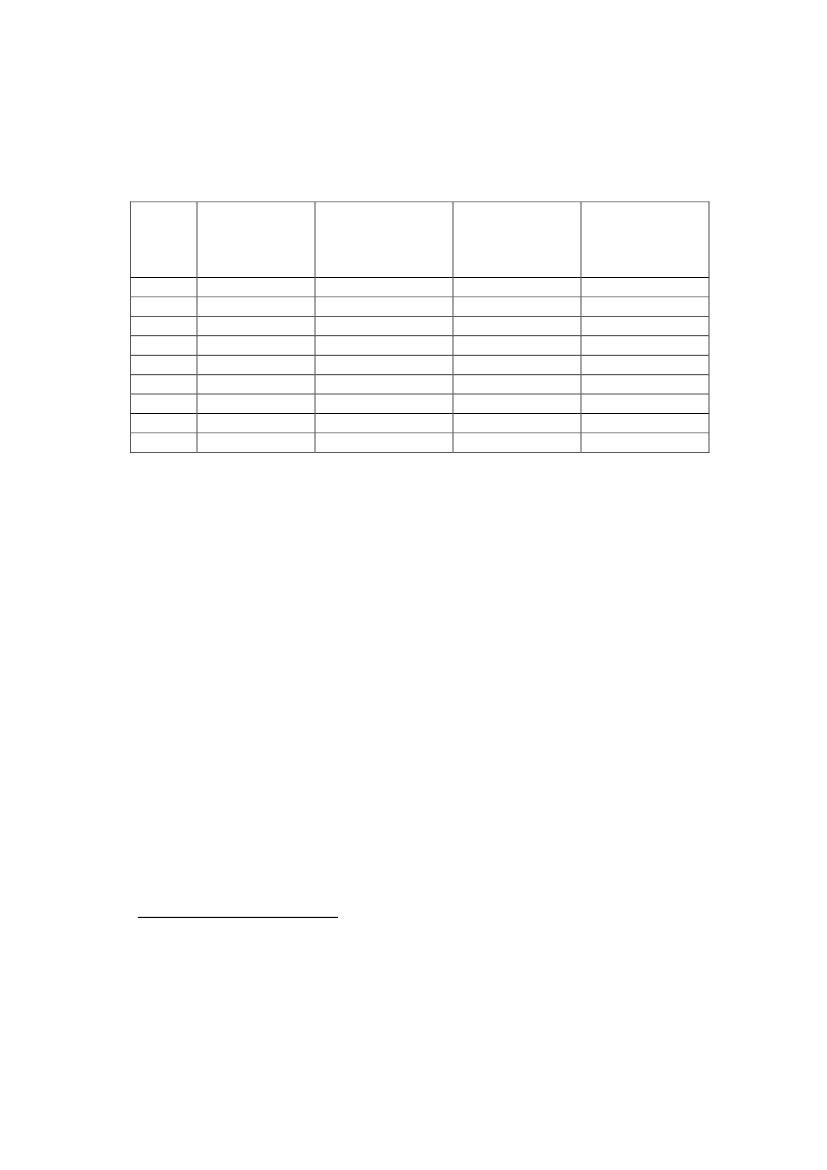

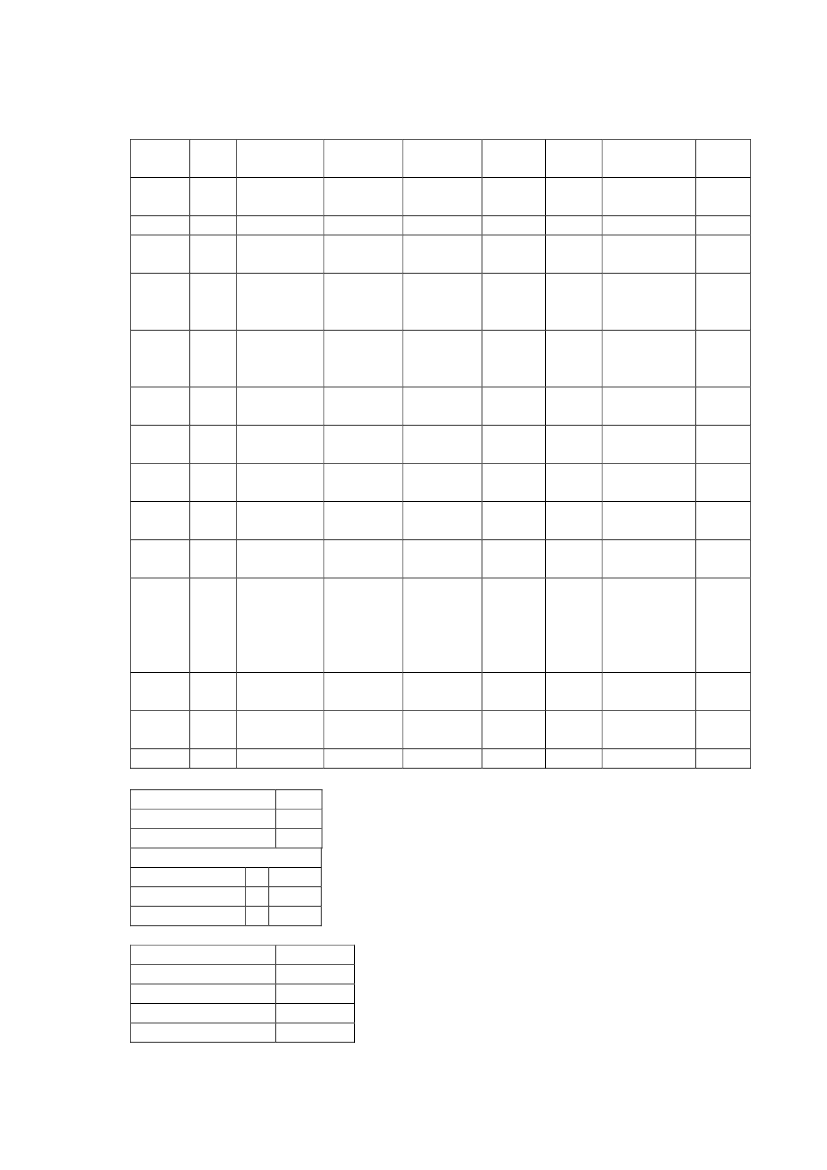

Table 4: Applications granted for permanent residence; refugees, broken down by agegroup.Age groupUnder 1818 years oldOver 18TotalSource: Aliens Service.20039804602292373220041430151330048812005137410030484522200651041975152620071102531244720081996145371320098954275418

Table 5 Applications granted for permanent residence; migrants reunified with fami-lies, broken down by age groups.Age groupUnder 1818 years oldOver 18TotalSource: Aliens Service.2003306584940562820043795248685857200544105435414639200647107499421152007218015191341200897116010882345200934107112032308

No general statistical information is available about the number of applicantsfor permanent residence who have taken part in the language test, etc., howmany failed/passed and how many times they have taken the test. However,the Ministry for Integration collects, processes and disseminates general sta-tistics concerning Danish language education; according to these statistics,37,833 students followed a Danish course in 2008; of these, some participatedin more than one Danish course, which means that this year the number ofeducational courses was 38,901. The distribution of students in percentageswas 8 per cent at DC1, 38 per cent at DC2 and 53 per cent at DC3.49The educated guess from the language school representatives inter-viewed during this research is along the same lines since it is estimated thatin 2010, 30-40 per cent will enrol in DC2 and 50-60 percent in DC3, while therest, about 6 -10 per cent enrol in DC1.More than half of all the students are self-supporting immigrants. In2008, 38.6 per cent of the students were self-supporting and paid a fee, and21.7 per cent were self-supporting but did not pay a fee. In particular, theself-supporting students following DC3 (in 2008 72.4 per cent of students inDC3 were self-supporting and, among them, 47 per cent paid a fee to followthe course).50

49

50

See Ministry of Integration:Tal og Fakta – Tema: aktiviteten hos udbydere af danskuddannelsefor voksne udlændinge m.fl. i 2007 og 2008(2010): http://www.nyidanmark.dk/NR/rdonlyres/86E12CC0-498C-4B0A-A3C5-A76419BE8336/0/aktivitet_danskudd_2007_08.pdf.Ibid,p. 10-12. Also at DC2 the self-supporting students are a majority.

35

DENMARK