OXFAM BRIEFING NOTE

NOVEMBER 2017

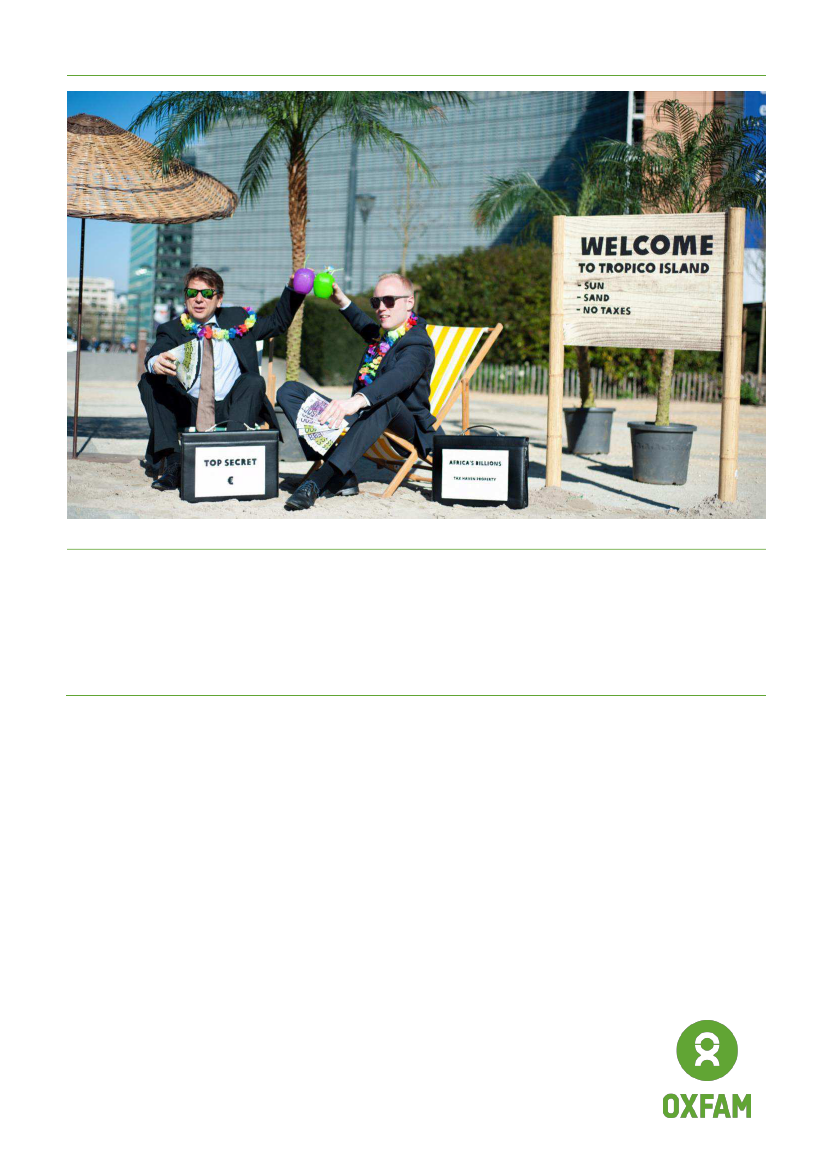

Oxfam tax havens stunt outside the EU offices in Brussels. Photo: Tineke D'haese/Oxfam

BLACKLIST OR WHITEWASH?

What a real EU blacklist of tax havens should look like

EMBARGOED UNTIL

23:01

HRS CET TUESDAY 27 NOVEMBER 2017

Tax havens deprive countries of hundreds of billions of dollars, fuelling

inequality and poverty. The EU will soon release a blacklist of tax havens

operating outside the EU, and issue penalties for those appearing on it.

However, power politics means that several significant tax havens could

be missing from the list. This report shows what a robust blacklist of tax

havens would look like if the EU were to objectively apply its own criteria

and not bow to political pressure. It also reveals four EU countries that

would be blacklisted if the EU were to apply its own criteria to member

states.

While the EU’s criteria are not perfect and will not capture all tax

havens, they are a step in the right direction. An objective blacklist,

combined with powerful countermeasures, could go a long way towards

ending the era of tax havens.

www.oxfam.org