Europaudvalget 2023

KOM (2023) 0600

Offentligt

EUROPEAN

COMMISSION

Brussels, 24.5.2023

SWD(2023) 638 final

COMMISSION STAFF WORKING DOCUMENT

In-depth review for Luxembourg

Accompanying the document

COMMUNICATION FROM THE COMMISSION TO THE EUROPEAN

PARLIAMENT, THE COUNCIL, THE EUROPEAN CENTRAL BANK, THE

EUROPEAN ECONOMIC AND SOCIAL COMMITTEE, THE COMMITTEE OF

THE REGIONS AND THE EUROPEAN INVESTMENT BANK

2023 European Semester – Spring Package

{COM(2023) 600 final} - {SWD(2023) 628 final} - {SWD(2023) 629 final} -

{SWD(2023) 630 final} - {SWD(2023) 631 final} - {SWD(2023) 632 final} -

{SWD(2023) 633 final} - {SWD(2023) 634 final} - {SWD(2023) 635 final} -

{SWD(2023) 636 final} - {SWD(2023) 637 final} - {SWD(2023) 639 final} -

{SWD(2023) 640 final} - {SWD(2023) 641 final} - {SWD(2023) 642 final} -

{SWD(2023) 643 final} - {SWD(2023) 644 final}

EN

EN

kom (2023) 0600 - Ingen titel

Luxembourg

In-Depth Review 2023

kom (2023) 0600 - Ingen titel

On the basis of this in-depth review for Luxembourg undertaken under

Regulation (EU) No 1176/2011 on the prevention and correction of

macroeconomic imbalances, the Commission has considered in its

Communication “European Semester – 2023 Spring Package” (COM(2023)

600 final) that:

Luxembourg

is not found to experience imbalances. Vulnerabilities relating to

high house prices and high household debt have recently increased but overall

seem to be contained so far and are expected to ease over the medium term.

Strong population growth alongside increased mortgage credit, incentivised by

fiscal support, has pushed up demand for housing, while supply has been

restricted by the limited land available for construction and by land hoarding. The

widening gap between housing demand and supply has resulted in strong house

price increases with growing risks of house prices overvaluation and deteriorating

affordability. House prices clearly cooled in late 2022, and the number of housing

transactions declined sharply, as the rise in interest rates have led to a turn in the

market. However, a sharp correction in house prices is not expected as incomes

are holding up well and the supply shortage is expected to continue. Household

debt is very high in terms of disposable income and has been increasing while

borrowing cooled somewhat in late 2022. Households’ financial assets are also

substantial, indebtedness increases towards the higher levels of income and

wealth, and the banking sector is sound, which overall mitigates macro-financial

risks. Additional policy efforts, including by stepping up and prioritising the

adoption and implementation of recent measures, including recurrent taxes to

increase the supply of buildable land, combined with the ongoing reform of land-

use planning, could help to boost housing supply, including through the supply of

affordable and social housing targeted to those most in need. The efficiency of

the rental market could be improved too. In addition, reducing the mortgage

interest deductibility, which was recently significantly increased, would reduce the

fiscal incentives to borrow which supports high house prices.

kom (2023) 0600 - Ingen titel

CONTENTS

1. Introduction

2. Assessment of macroeconomic vulnerabilities

4

5

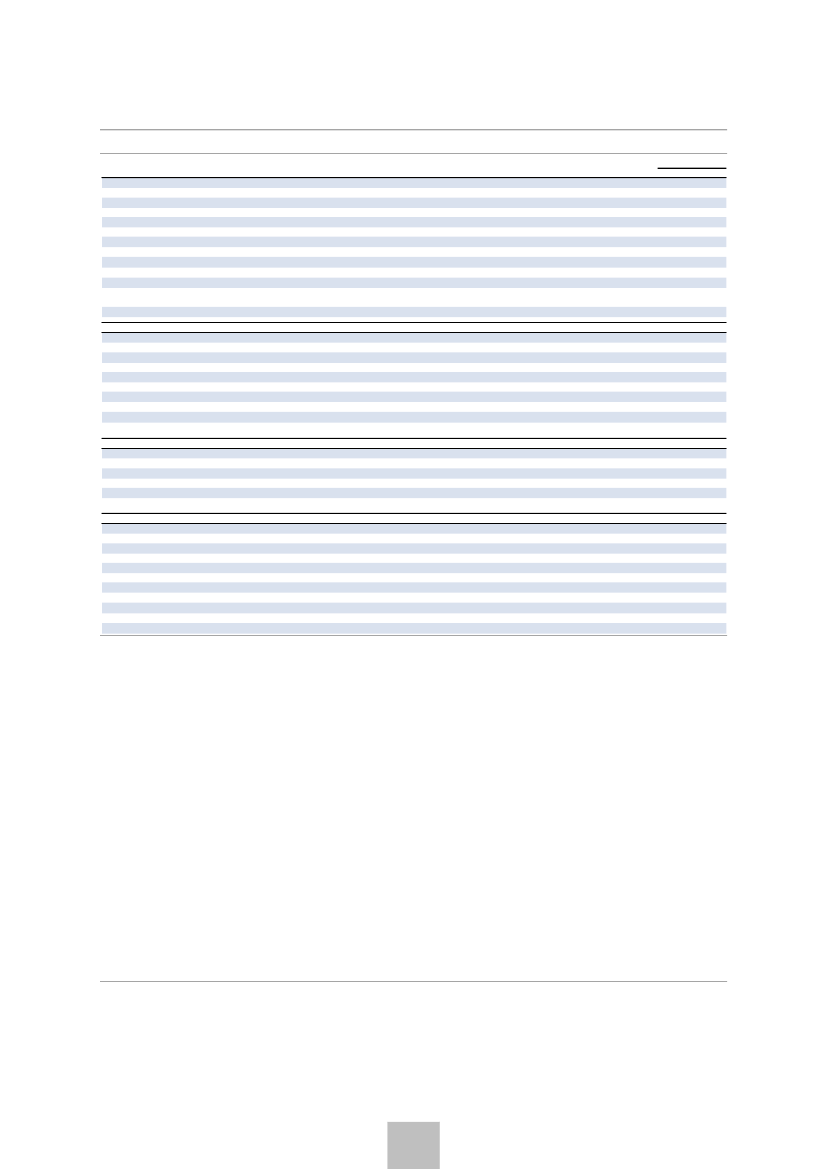

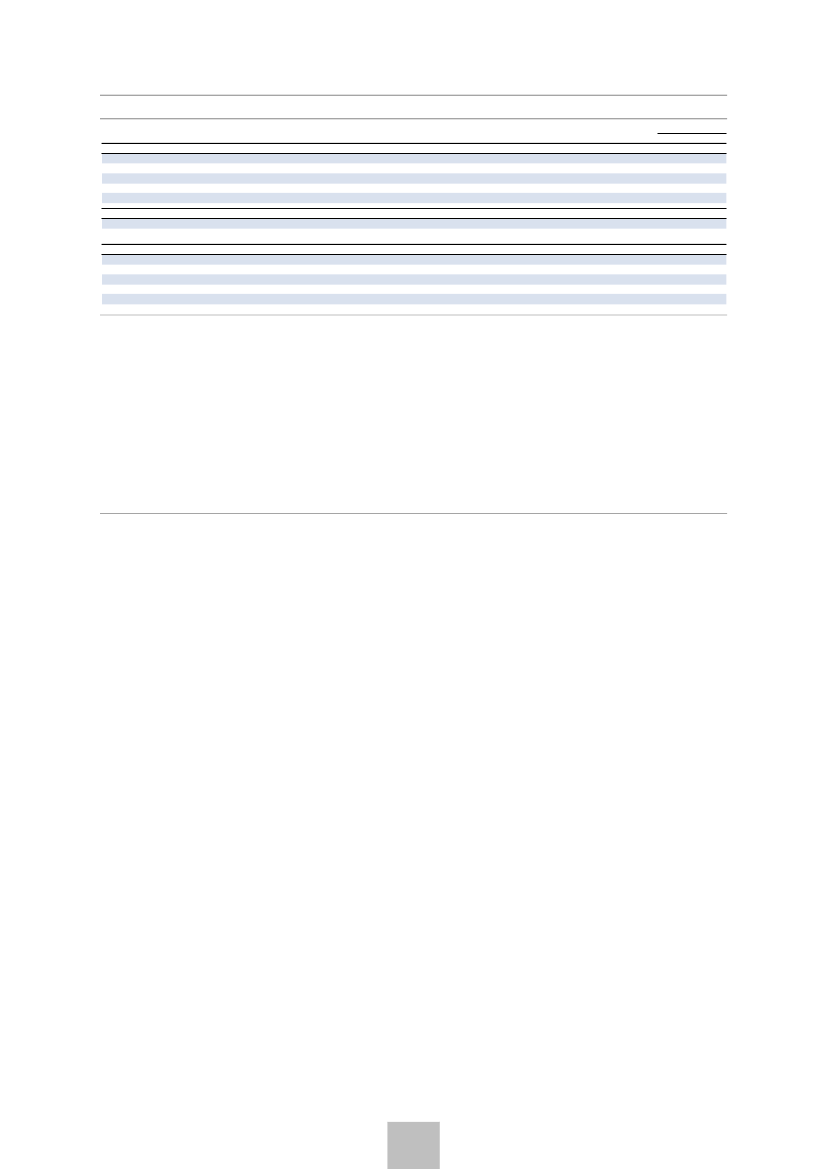

LIST OF TABLES

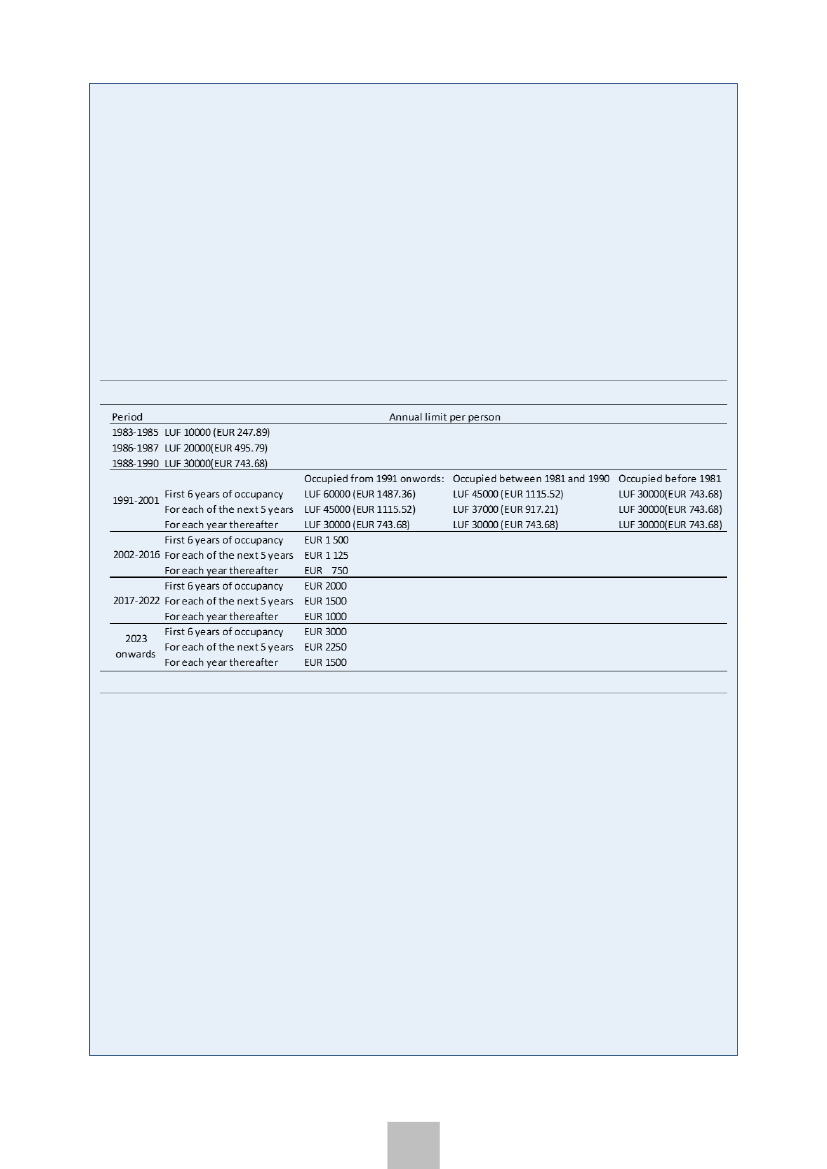

Table 2.1:

Table 2.2:

Table 2.3:

Table 2.4:

Evolution of maximum mortgage interest deductible from taxable income

Impact of different MITR policies in households borrowing capacity

Selected economic and financial indicators (Part 1), Luxembourg

Selected economic and financial indicators (Part 2), Luxembourg

13

15

19

20

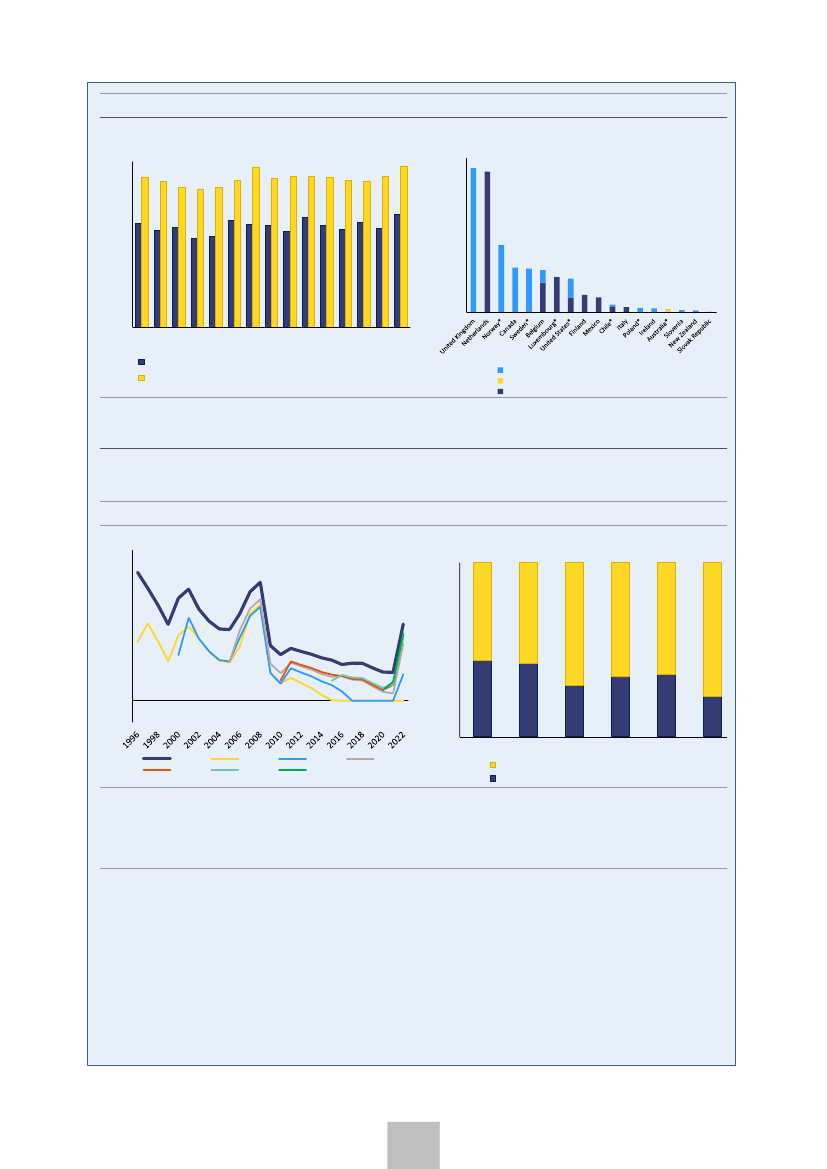

LIST OF GRAPHS

Graph 2.1:

Graph 2.2:

Graph 2.3:

House price, credit, population, and employment

Price-to-income ratio

House price, rent and income (nominal terms) in Luxembourg and household debt-to-income ratio in EU Member

States

Graph 2.4:

Graph 2.5:

Graph 2.6:

Graph 2.7:

Share of owners and foregone tax revenue

Nominal interest rate

Selected graphs, Luxembourg

Components of gross fixed capital formation deflator growth and consumer price inflation

9

14

14

17

18

6

7

kom (2023) 0600 - Ingen titel

1.

INTRODUCTION

In 2022, over the previous annual cycle of surveillance under the Macroeconomic

Imbalance Procedure (MIP), Luxembourg was not subject to an in-depth review to assess

its vulnerabilities.

(

1

) The 2023 Alert Mechanism Report published in November 2022 concluded

that an in-depth review (IDR) should be undertaken for Luxembourg this year, with a view to

examine newly emerging vulnerabilities and their implications. (

2

) The AMR concluded that in

Luxembourg, concerns related to house price developments and high household debt had increased.

Nominal house price growth was among the highest in the EU, raising concerns about overvaluation

and high household debt. Household debt as a percentage of household gross disposable income

was declining but remained very high. The banking sector was stable but faced some risks. Some

competitiveness concerns may have been emerging, amid continued unit labour cost growth.

Luxembourg’s GDP growth was above the EU average in recent years driven by solid

domestic demand and net exports.

The economy fared relatively well during the COVID-crisis

mainly due to the large share of services in the economy and significant government support.

Following a strong recovery from the pandemic in 2021, with GDP growth of 5.1%, Luxembourg’s

economic activity slowed to 1.5% in 2022. This decline was mainly due to lower private

consumption and a fall in investments following high inflation, tighter financing conditions and

geopolitical uncertainty. Going forward, real GDP growth is projected to be at 1.6% in 2023, before

recovering to 2.4% in 2024, mainly due to an improvement in net exports and investments. (

3

)

Following the headline inflation peak of 8.2% in 2022, on the back of elevated energy and food

prices, inflation is projected to decrease significantly to 3.2% in 2023. This can be explained by the

projected decrease in energy prices in combination with the fiscal support measures to limit

inflation that were extended until end 2024. A further decline to 2.6% is forecast for 2024, due to

a fall in all inflation components. Core inflation is expected to remain high in 2023 mainly driven by

the increase in compensation of employees, before declining in 2024.

This in-depth review presents the main findings of the assessment of macroeconomic

vulnerabilities for Luxembourg.

The assessment is backed by a thematic section on the housing

market. Vulnerabilities related to housing in Luxembourg are also discussed in a horizontal

thematic note that was recently published. (

4

) The MIP assessment matrix is published in the 2023

Country Report for Luxembourg. (

5

)

(

1

) European Commission (2022), European Semester Spring Package 2022, COM(2022) 600 final.

(

2

) European Commission (2022), Alert Mechanism Report 2023, COM (2022) 381 final.

(

3

) European Commission (2023), European Economic Forecast: Spring 2023, Institutional Paper 200.

(

4

) European Commission (2023), Housing Market Developments: Thematic Note to Support In-Depth Reviews, European

Economy: Institutional Papers, 197.

(

5

) European Commission (2023), Country Report Luxembourg 2023, SWD(2023) 616 final.

4

kom (2023) 0600 - Ingen titel

2. ASSESSMENT OF MACROECONOMIC

VULNERABILITIES

Gravity, evolution and prospects

On 5 April 2023 the Commission presented a horizontal thematic note on housing

market developments, including Luxembourg.

It demonstrated that house prices in

Luxembourg have more than doubled in nominal terms over the last decade, with a large share of

this increase taking place over the last four years. As a result, the price-to-income ratio experienced

one of the highest increases in the EU, reflecting affordability issues. Strong economic and

demographic dynamics have driven housing demand, while supply has persistently lagged.

However, a potential correction of house prices, following a significant increase in interest rates and

an increase in unemployment, and considering the high household mortgage debt, raises financial

stability concerns for the domestically oriented banks, which hold roughly 90% of mortgage debt.

Over the last decade, house prices in Luxembourg have increased markedly.

Between

2012 and 2022, house prices have increased by 118% in nominal terms (44% in the euro area),

with half of this increase taking place over the last four years. The continued strong increase of

house prices in 2021, led the ESRB to conclude in February 2022 that real-estate related risks were

high and that the measures in place were only partially appropriate and partially sufficient and

argued for additional income-based measures, such as debt-to-income limits. (

6

) In 2022, a

slowdown in house price growth was observed following the tightening of financing conditions. The

y-o-y growth in 2022 still amounted to 9.6% (13.9% in 2021 and 14.5% in 2020), but the fourth

quarter saw a decline in prices versus the previous quarter (-1.4%). Also the number of transactions

and the mortgage volumes showed a decrease in line with the slowdown of the housing market. In

2022, house prices in Luxembourg have remained less sensitive to changes in the economic and

financial environment, compared to other Member States.

Statistical indicators suggest that the long-term price increases have led to an

overvaluation in the Luxembourg housing market.

The Commission estimates the

overvaluation gap in Luxembourg at 63% in 2022. (

7

) This is an unweighted average of three

indicators in the range of 10% to 97%, which shows the wide variety of these estimates, although

all point to an overvaluation. (

8

)

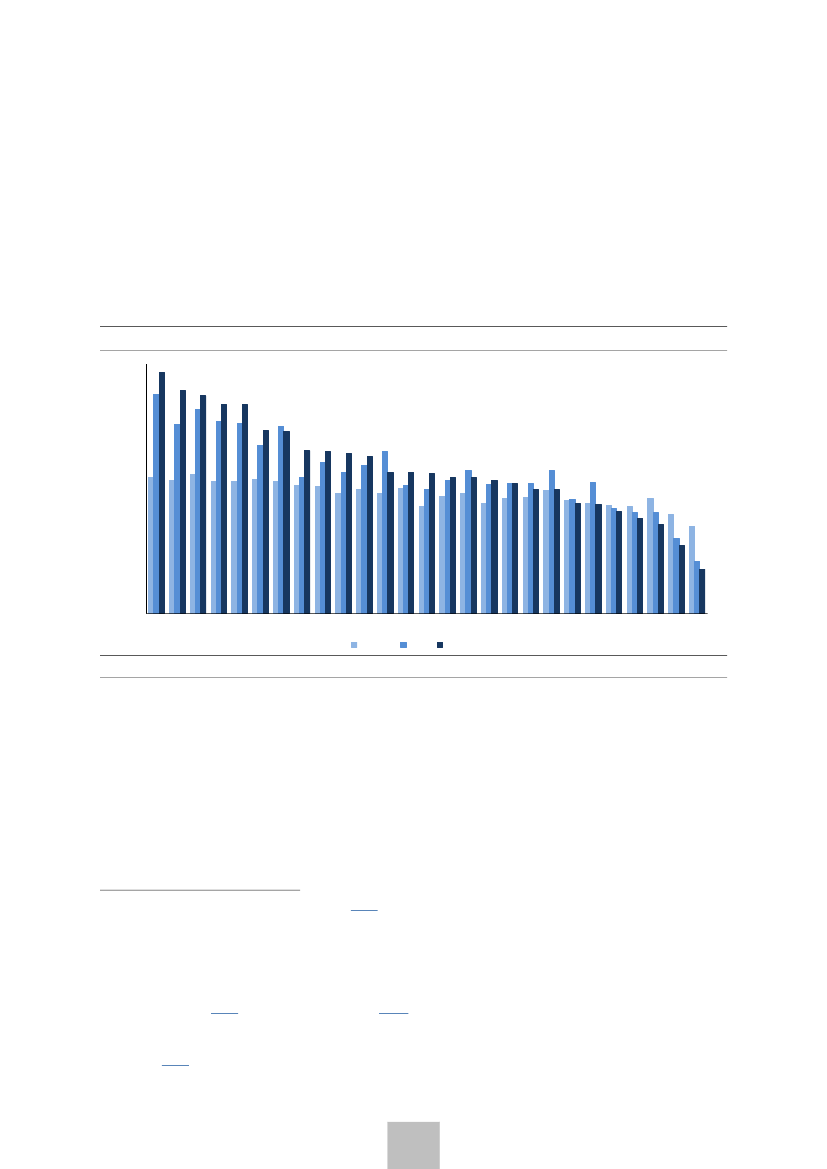

House prices have increased faster than income, raising affordability concerns.

The

affordability issue is evidenced by the growth divergence between households’ income and house

prices, especially since 2015; real disposable income per head grew by 8%, while real house prices

increased by 63% between 2015 and 2022. Therefore, the price to income ratio has risen by

around 50% since 2015, one of the highest increases among the euro area Member States in

(

6

) ESRB, Vulnerabilities in the residential real estate sectors of the EEA countries February 2022.

(

7

) The Commission overvaluation gap is the unweighted average of the price-to-income (81%), price-to-rent (97%) and

model valuation gaps (10%). The latter is an econometric model based on fundamental drivers; population, interest rates

and housing supply (see also table 2.4).

(

8

) BCL reported in their Financial Stability report 2022 an 26% overvaluation in first trimester 2022, the ECB reports a 54%

average overvaluation gap end 2022.

5

kom (2023) 0600 - Ingen titel

2.

Assessment of macroeconomic vulnerabilities

2021. (

9

) The affordability concern is aggravated by the fact that only 2% of the total housing

stock is rented at social and affordable prices. (

10

)

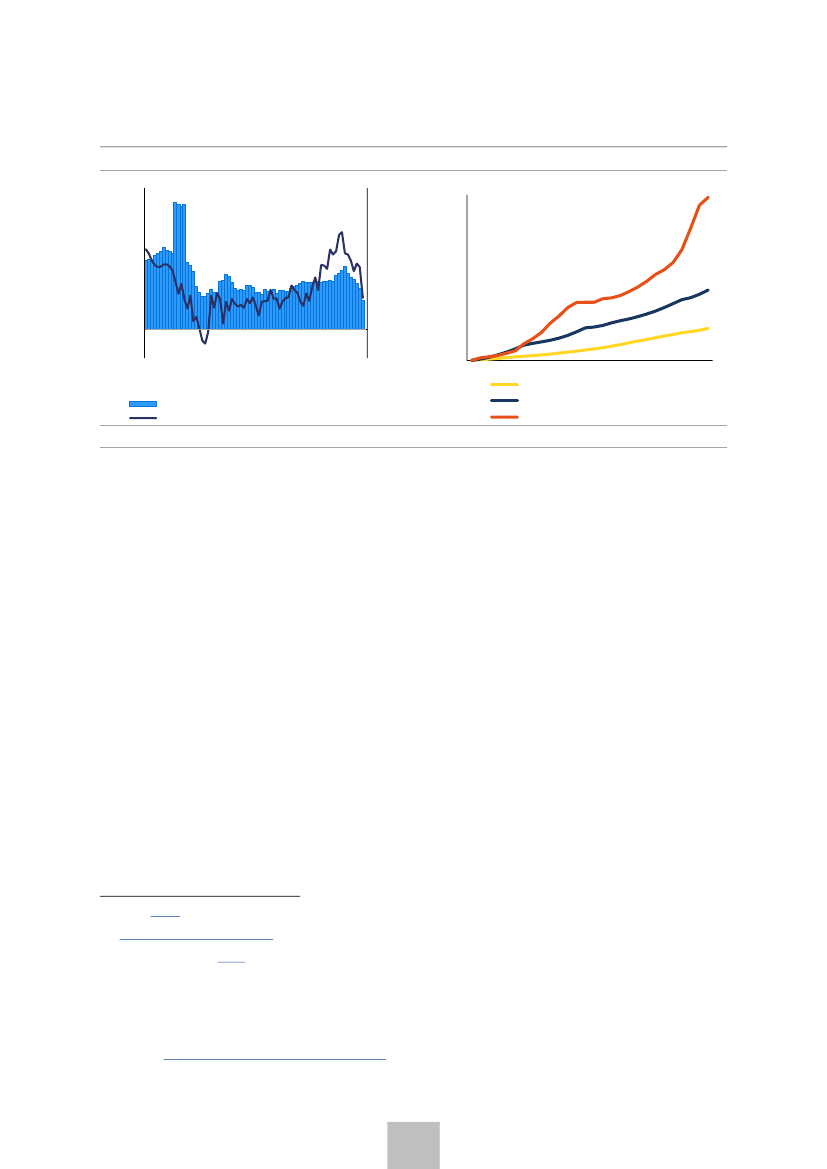

Graph 2.1:

House price, credit, population, and employment

25

a)Real house price and mortgage growth

25

400

20

Rate of change y-o-y (%)

15

10

5

0

-5

b) Evolution of house prices, population and

employment

20

350

15

10

5

0

-5

Rate of change y-o-y (%)

1995 = 100

300

250

200

150

100

95 97 99 01 03 05 07 09 11 13 15 17 19 21

Population

04Q4

05Q4

06Q4

07Q4

08Q4

09Q4

10Q4

11Q4

12Q4

13Q4

14Q4

15Q4

16Q4

17Q4

18Q4

19Q4

20Q4

21Q4

22Q4

MFI loans for house purchase (y-o-y growth rate)

Nominal House Price Index (y-o-y growth rate), right axis

Employment in resident production units

Deflated house price index

Source:

Eurostat, ECB and European Commission services

The strong economic growth has led to a high increase in employment and disposable

income, also stimulating demand for housing and mortgage credit.

An uneven acceleration

of demand across income quartiles was observed in recent years. It was especially strong among

the higher income levels, while demand from the bottom quartiles decreased in relative terms. Four

packages of high energy price support measures have been adopted by the government since

2021, supporting income and employment until the end of 2024.

Demand was further stimulated by a higher participation of (foreign) investors attracted

by the high house price increases.

The higher participation from investors, notably in the market

segment of newly built apartments, also contributed to pushing up house prices. Over 40% of this

type of dwellings were purchased by investors between 2015 and 2021 (

11

), pointing to a demand

shift towards buy-to-let investments. The fall in real (

12

) rental yields did not discourage buy-to-let

investors. This implies positive expectations on tax advantages and capital gains. (

13

) Investors’

participation seems to have started to decline in 2021 following the 80% loan-to-value (LTV)-limit

and more strongly in 2022 following the rise in interest rates. Despite the increases, buy-to-let

housing remains limited in the housing market. (

14

)

The strong increase in mortgage credit has fuelled the large house price increases, and

fiscal support has contributed to this.

The growth in employment and income combined with

very low financing costs and strong fiscal support have spurred mortgage growth since the 2008-

2009 financial crisis. Borrowers benefited from historically low mortgage rates, which increased

their capacity to borrow. The large fiscal support to home ownership partly explained the higher

credit growth in recent years, compared to other Member States (see also Box 1). The 2017 tax

(

9

) ESRB,

2022.

(

10

)

Note-30-en-bref.pdf (public.lu).

(

11

) Ministry of housing,

2022.

(

12

) In January 2021, differentiate loan-to-value limits were enforced: 100% for first time buyers, 90% for primary residents

and 80% buy-to-let and other investors.

(

13

) Rental income is also capped at 5 percent of the purchase value of the dwelling, but tax deductions stimulate the return on

investment during the first five years after purchase. Rents can be revalued when tenants change.

(

14

) Eurostat

House or flat – owning or renting (europa.eu).

6

kom (2023) 0600 - Ingen titel

2.

Assessment of macroeconomic vulnerabilities

reform abolished the taxable rental value and increased mortgage interest deduction for the main

residence and introduced an increased threshold for deducting home purchase savings

contributions. In 2015, the ceiling for the VAT super reduced rate on newly constructed home,

previously linked to the value of the house, was replaced by a ceiling on deductibility. In 2017, the

temporary budgetary compensation tax of 0.5 percent was abolished, and several tax credits have

been introduced. Together, these various fiscal measures represent large support. (

15

) This makes

Luxembourg as one of the highest spenders on housing subsidies in advanced economies. The

borrowing capacity of most households have decrease due to higher mortgage rates in 2022 and a

deterioration of real incomes due to elevated inflation. This is slowing down demand and a sharp

decline in the growth rate of mortgages has been observed. (

16

) In the last high energy price

support package, the government took two fiscal measures to support mortgage demand (see also

policy section).

Graph 2.2:

Price-to-income ratio

150

125

2015 = 100

100

75

50

LU

NL

PT

CZ

AT HU DE

IE

ES

SI

SK

DK

LV

EE

FR

SE

LT

BE

EL MT HR

PL

FI

IT

BG

CY

RO

2014-20

2021

2022

Source:

Eurostat and European Commission services

Strong demographic dynamics have driven up the housing demand, with housing supply

persistently lagging demand.

Between 2010 and 2021, the population increased by around 30%

(versus 5% in the euro area), more than 7,000 households per year (

17

). Meanwhile, the pace of

production of new dwellings was below 4,000 units per year (Graph 2.6, panel b), significantly

below estimated demand between 6,200 and 8,000 (

18

). This has resulted in a structural housing

shortage and increased pressure on house prices. This has been partly mitigated by the cross-

border housing market, with an increasing number of non-resident workers commuting across

borders every day, mainly from Germany, France and Belgium. Commuting workers reached 204.6

thousand in 2021, around 42% of domestic employment. This creates a large pool of pending

demand for housing in Luxembourg. The low supply of housing is also due to the high concentration

(

15

) Estimated at 2.5% of GDP by Girshina, A. et al.

2022.

(

16

) BCL statistic tables (11.7 and 11.9).

(

17

) Furthermore, population is playing a critical role in the county’s broad economic performance, and in particular in the

sustainability of public finances over the long term. In this regard, Luxembourg has been repeatedly addressed Country

Specific Recommendations to ensure the sustainability of its public finances. This is part of the macroeconomic and

budgetary surveillance carried out by the Commission in the framework of the European Semester (see Council

Recommendation,

2022,

and European Commission,

2021,

for a detailed presentation of estimates).

(

18

) Estimated housing demand range between 6,200 and 8,000 housing units per year, from 2018 to 2030, required to

achieve a GDP growth of 3% on average per year, depending on the assumptions on the share of cross-border workers

STATEC,

2019.

7

kom (2023) 0600 - Ingen titel

2.

Assessment of macroeconomic vulnerabilities

of land (

19

) which allows landowners to adjust markups and reap a larger share of the fiscal

support to homeowners. (

20

)

The stock of social housing is one of the lowest in the EU.

The limited stock partly reflects

the preference of public providers who used to allocate about one third of constructed units to

renting and two thirds for sale and the past practice of allowing re-sale of subsidised housing on

the non-subsidised housing market.

Construction activity has slowdown in 2022, driven by the rise in interest rates, but the

impact on GDP is expected to be small.

Construction activity started to slow down in 2021,

following disruptions in production chains and higher inflation, which significantly raised

construction costs. With the rise in interest rates housing demand from households and buy-to-let

investors (

21

) weakened, slowing down supply and reducing construction activity. The lower activity

in residential construction is expected to have a small impact on the country’s aggregate economic

growth, since its weight is less than 5% in GDP. (

22

)

Existing rental prices have increased much slower than consumer prices, in contrast with

advertised rents that have even accelerated in the short term.

Rental prices increased by

1.3% on average per year from 2010 to 2022, which was lower than growth of the harmonised

consumer prices, despite a small acceleration in 2022 to 2%. Existing rents are not regularly

adjusted for inflation, partly because automatic indexations are not enforceable in lease contracts

and need to be negotiated between the owner and the tenant. New rents are significantly higher

than existing ones. Advertised (

23

) rental prices increased by around 3%, on average per year, in line

with inflation, and accelerated significantly, (by 8.0% in Q4-2022 year-on-year) in line with the

harmonised index of consumer prices (8.4% in Q4-2022 year-on-year). This increase might be

explained by further demand shifting from home ownership towards renting, a trend also observed

in previous years (between 2017 and 2021 the share of tenants increased by 3.6pps to 28.9%). (

24

)

This could be due to increased affordability problem, which is likely to be aggravated by the

introduction of loan-to-value limits in 2021 and the rise in interest rates in 2022.

The rise in interest rates has led to a turn in the housing market but a sharp correction

in house prices is not expected.

While the financial cycle has entered a downward trend a sharp

housing price drop is not expected. The impact on prices tends to be dampened by supply

adjustments (

25

), therefore price volatility from a cyclical downturn is expected to be weaker in

Luxembourg, compared with other Member States. Although house prices declined q-o-q in

Q4-2022, for the full year a still high price growth of 9.6% was observed. Considering the sharp

decline in the number of transactions and mortgage credit amounts, such a steady growth in house

prices appears remarkable. It also results from the practice of sales retention by developers to

(

19

) Despite the relative abundance of constructible land in Luxembourg, land supply appears to be a key limiting factor for

housing supply, supporting house price inflation. The price of constructible land, which accounts for 20%-40% of the

housing sales value, increased by 136.5% between 2010 and 2021, higher than house prices.

(

20

) Girshina, A. et al.

2022.

(

21

) Since rising interest rates makes real estate investment more expensive, and at the same time alternative investments

become relatively more profitable.

(

22

) According to Luxembourg Annual National Accounts, Gross fixed capital formation dwellings and GDP (EUROSTAT).

(

23

) This indicator is published by STATEC based on data collected from estate retailers and provides a gauge of current prices

for households accessing the rental market, as opposed to the standard indicator of rental prices, which includes all existing

rents. Figures need to be taken with care though, since they are not adjusted for the characteristics of the dwellings

announced and may diverge from the rent eventually agreed between owner and tenant.

(

24

) Eurostat:

Statistics | Eurostat (europa.eu).

(

25

) In this line, house sellers respond swiftly, adjusting activity, to dampen negative short-term price dynamics.

8

kom (2023) 0600 - Ingen titel

2.

Assessment of macroeconomic vulnerabilities

sustain price levels (

26

), in expectation of demand to recover momentum. (

27

) The labour market is

expected to remain resilient with solid domestic employment growth of 2.4% in 2023 and 2.3% in

2024 and a low level of unemployment (4.8% in 2023 and 5.0% in 2024) (Commission Spring

2023 forecast). Therefore, disposable income, supported by the automatic wage indexation, is

expected to continue to grow. After the ’absorption’ of the interest rate shock, the structural higher

demand versus supply is expected to continue to drive house price increases.

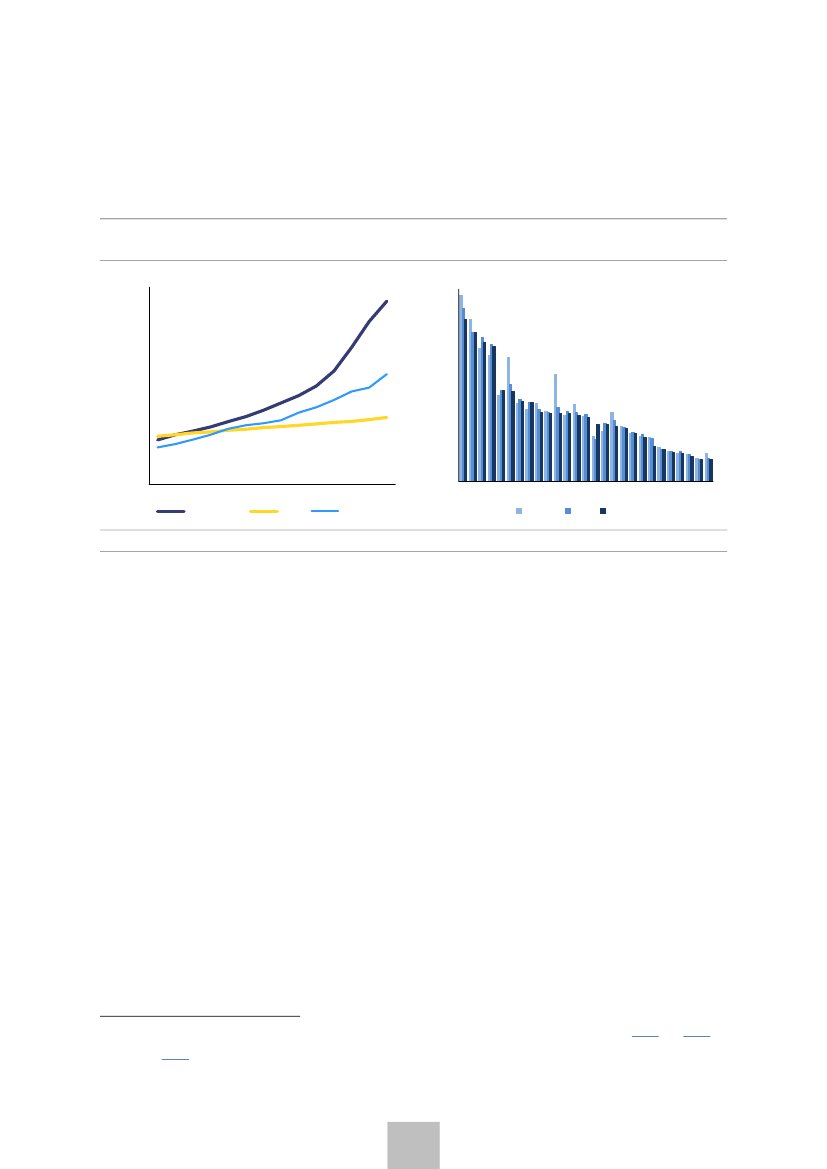

Graph 2.3:

House price, rent and income (nominal terms) in Luxembourg and household debt-to-

income ratio in EU Member States

250

a) Evolution of house prices, rents and household

income

250

b) Household debt

(2010=100)

200

% of gross disposable income

200

150

150

100

100

50

09 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22

House prices

Rent

Income

Source:

Eurostat and European Commission services

In recent years, concerns have increased with regard to the housing market because of

the high household debt, especially in terms of disposable income.

Household debt as

percentage of disposable income continued trending upward and is substantially higher compared

to other Member States. At an aggregate level, household debt reached 180% of disposable

income in 2022, 61% above its long-term average, which is one of the highest deviations from its

historical average among the EU Member States. Household debt is largely attributable to the

strong growth in residential real estate loans, as bank mortgages account for more than 80% of

household debt (146% of disposable income). A long period of supportive financial conditions and

fiscal policies have favoured home ownership over tenancy contributing to sustain mortgage credit

growth. In line with growth of house prices, mortgage credit increased steadily since 2009, at a

stable rate of 5.4% on average in real terms (Graph 2.3). Households require a larger share of their

income to pay their mortgages, which limits the access to home ownership for an increasing

proportion of the population, especially among lower income households, such as starters and

young households.

The risk for the domestic banks is mitigated because a large share of debt is owed by

wealthy households.

Luxembourg’s has a large financial sector but just a few national banks are

exposed to the housing market. Domestic banks are exposed to vulnerabilities related to high

housing price declines and the high household debt. However, a significant share of the financial

sector is internationally oriented and with a high level of foreign ownership. The activities of foreign

banks are mainly cross-border intra-company and international corporate finance and investment

focused and therefore have a limited interaction with domestically oriented banks. Households’

financial assets are also high, therefore mortgage debt appears to be well covered by the liquid

financial assets at an aggregate level. Net financial assets compared to the national income are

(

26

) The construction sector is run by a few large companies, which also own land (Observatoire de l'Habitat,

2022

and

2021).

(

27

) STATEC,

2023.

9

DK

NL

SE

LU

FI

CY

BE

FR

PT

MT

IE

DE

ES

AT

HR

SK

EL

EE

IT

CZ

PL

SI

BG

LT

HU

RO

LV

2014-20

2021

2022

50

0

kom (2023) 0600 - Ingen titel

2.

Assessment of macroeconomic vulnerabilities

close to the euro area aggregate, at 267%, and total savings and deposits, which reached

EUR 54.7 billion in Q3-2021, are above the aggregate stock of debt of EUR 50.9 billion. Moreover, a

distributional perspective on mortgage affordability and debt-to-income and wealth levels point to

lower vulnerabilities in the household sector than the aggregate measures might suggest. In

addition, lower income households hold lower debt, as breakdowns of households by both income

and wealth show. Among the lower income households there are relatively fewer homeowners and

more tenants. Whereas the average cost of mortgage loans increased over the period 2020 to

2022, it remains low, rising from 1.32% to 1.46%, while only 5.4% of homeowners with a

mortgage had a housing debt burden above 25% of their disposable income, compared with 13.6%

in the EU. (

28

) Furthermore, the proportion of mortgages at adjustable rates has significantly

decreased recently and currently stands at 40%, while most of the mortgages granted in recent

years were at fixed rates. (

29

) Finally, the highly resilient labour market and very low unemployment

rates, sound public finances and strong social security are important factors supporting borrowers’

debt servicing capacity and contributing to the high level of financial stability in Luxembourg.

Banks’ buffers appear sufficient to absorb potential shocks stemming from the

residential real estate market and mortgage debt.

Nearly 90% of mortgage debt is held by

five domestically oriented banks (out of around 120 MFIs operating in Luxembourg) and accounts

on average for around 25% of their total assets. The effects of stress tests carried out by the

Central Bank of Luxembourg showed a potential decline in the solvency ratio ranging from 0.8pps

to 3.1pps, to reach a ratio of 15.9% in the worst-case scenario of a fall in residential property

prices induced by the estimated default probabilities. (

30

) The weighted average loan-to-value ratio

of the domestic banks active in the residential real estate market, declined from around 78% to

76% in 2021, while the weighted average loan service to income ratio of the five domestic banks

has crept up over the past two years, from 28% in the first half of 2019 to 33% in the second half

of 2021, which is relatively low compared to other Member States. Therefore, the data in 2021

suggests that the introduction of additional capital measures and loan-to-value limits had a

dampening effect on mortgage loan flows and domestic banks appear to have sufficient capital to

absorb housing market shocks.

In general, banks are well capitalised and liquid, and profitability has increased in 2022.

Financial risks for the banking sector mainly stem from the impact of further monetary policy

tightening and the potential heightened volatility in financial markets. Despite the high level of

uncertainty surrounding economic activity, banks’ balance sheets are sound. The rising key rates

weigh on demand for loans, but also support banks’ net interest rate margin, which increased by

39% in 2022 and is expected to increase also in 2023. (

31

) The common equity tier one (CET 1)

ratio remains at 17.6% well above the legal threshold, in Q2-2022 (at 21.4% for domestically

oriented banks). (

32

) The ESRB and BCL projections show that the credit-to-GDP gap, which is the

standard measure recommended by the ESRB to calibrate the counter cyclical capital buffer, turned

negative in 2022 and is expected to remain negative over 2023. (

33

) Although the level of credit-to-

GDP is below its long-term trend, due to the high degree of uncertainty surrounding these

projections, the National Systemic Risk Board decided to maintain the countercyclical capital buffer

at the level of 0.5%, in place since January 2021.

(

28

) BCL FSR 2022.

(

29

) BCL,

2022.

(

30

) BCL FSR 2022.

(

31

) STATEC,

2023.

(

32

) Macro charts Consolidated banking statistics for Luxembourg, domestic stand-alone banks.

(

33

) CdRS,

2023.

10

kom (2023) 0600 - Ingen titel

2.

Assessment of macroeconomic vulnerabilities

Assessment of MIP relevant policies

Household debt remains high in Luxembourg and is incentivised by mortgage interest

deductibility which was recently increased.

The government announced an increase of the

mortgage interest rate tax deductibility and a higher tax credit, as part of the government support

measures in Solidariteitpak 3.0. The government has announced a 50% increase of the mortgage

interest deductibility and an increase in the tax credit from EUR 20 000 to EUR 30 000 for

purchasing building land and residential buildings. Although, this measure is in response to the

higher interest rates and the currently observed slowdown in the housing market, its permanent

nature will further stimulate demand for housing that is already structurally high (see also Box 1).

Conversely, Luxembourg implemented LTV-limits in 2021, which should have a dampening effect,

although the ESRB concluded in 2022 that measures in place were only partially appropriate and

partially sufficient and argued for additional income-based measures, such as debt-to-income

limits.

The tax system favours homeownership compared to other housing tenures, such as

renting, which contributes to strong housing demand.

The favourable tax treatment of

owner-occupied housing is likely to benefit high-income households the most. This is particularly

true for the deductibility of mortgage interest, which is generally regressive, because high-income

households are much more likely to finance their house with mortgage debt. Gradually phasing out

mortgage interest rate deductibility would make taxation of owner-occupied property less

regressive. The introduction of a progressive recurrent tax schedule to the owner and an increase in

the recurrent taxes on immovable property that is based on regularly updated property values also

reduce regressivity of tax systems. However, unless cautiously designed, the introduction of higher

recurrent taxes can have a negative impact on affordability of households with low incomes and

less liquid assets.

The government has presented a package of three tax measures in order to address

some of the supply side obstructions.

The package contains a reform of the current land tax

(IFON), the introduction of a tax on the mobilisation of land (IMOB) and on the non-occupation of

dwellings (INOL). The tax measures aim to increase the supply of land and usage of constructable

land and unoccupied dwellings and therefore is a step in the right direction. However, the package

still needs to pass the legislative process and is implemented over several years, therefore, it’s too

early to assess its effectiveness in addressing the supply side vulnerabilities. The government also

presented some new amendments regarding the

Baulandvertrag

bill on 9 November 2020. This

draft law aims to improve the effectiveness of measures relating to the implementation of urban

development plans ("PAG") to speed up the construction process for new housing. In addition, the

government plans an increase in public investments in housing to support supply, raising them from

3% of total investments in 2022 (EUR 83mln) to 8% (EUR 313mln) in 2026 according to the multi-

annual budget.

Luxembourg does not have a dynamic rental market and rent setting is strongly

regulated.

An increase in the share of rental housing could improve the dynamics of the housing

market. The draft law on residential rental lease, tabled on 31 July 2020 by the Luxembourg

Minister of Housing, is still being debated and no solution before the elections in October 2023 is

foreseen. The law aims to reduce the ceiling on rents, set a maximum deposit amount as guarantee

and increase the transparency of the rent setting to get a ‘fairer’ private rental market. Especially

the rent setting policy with the current ‘5% rule’ does not seem to be effective in increasing

transparency nor limiting rent increases. In addition, the government aims to increase the

construction of rentals in the housing stock via both public and private developers.

11

kom (2023) 0600 - Ingen titel

2.

Assessment of macroeconomic vulnerabilities

The stock of social housing is one of the lowest in the EU.

However, efforts to increase the

share of social rental housing are underway. The sale of social housing has taken the form of a

long-term lease, which is welcome as it effectively captures the value of developed land, which

remains a property of the public housing providers. However, the provision of social and affordable

housing remains insufficiently for low-income households. To overcome existing municipal

resistance to densification, the Housing Pact 2.0 targets were extended to include additional

criteria, such as numerical targets for social housing construction for municipalities. (

34

) The

government plans to increase public investments to support the supply of affordable housing and

affordable and social rentals, in cooperation with the public promoters

Fonds de Logement

and

Société Nationale des Habitations à Bon Marché.

At the start of 2022, Luxembourg announced a

reform of the legal framework on housing to improve affordability. Housing support will be

reformed by two bills that will replace the current law. The first bill will establish a clear framework

for financing affordable housing and supporting its inhabitants. The second bill will extend and

simplify individual support schemes for housing, both rented and owned in the private market. The

objective of this reform is to ensure the right to housing and foster social cohesion. It is too early to

assess the impact of these bills on affordable housing supply at this stage.

The densification of the existing urban and suburban space in the immediate vicinity of

transport network hubs, in particular railway stations, facilitates the use of public

transport.

In that way, densification could lead to shorter commuting trips and encourage

alternative means of travel, which tends to be more competitive with car travel over short

distances. The measure for free public transport was appropriate in this sense. The recent

sustainable mobility strategy emphasises both the multimodal and cross-border dimension and

plans to double the number of park and ride facilities, including at the borders, by 2030. As the

main transportation flows also involve cross-border travel, infrastructure projects require

preparation with support and participation of the neighbouring regions and close involvement of

border municipalities, public and private providers of rail and road transport.

(

34

) One of the Housing Pact 2.0 objectives is a higher number of affordable housing in each ’plan d’aménagement particulier

nouveau quartier’ (PAP NQ)”: a certain percentage of the constructed gross area for housing (10% min) is reserved for

affordable housing. The land on which these houses will be built is transferred to the municipality or the State. In return, the

building potential reserved for housing is increased by 10% compared to the ‘plan d’aménagement général‘ (PAG).

12

kom (2023) 0600 - Ingen titel

2.

Assessment of macroeconomic vulnerabilities

Box 1: Mortgage Interest Tax Relief in Luxembourg

Taxation has been used in many countries with the objective of subsidising homeownership. One of

the most common used tax policies is the possibility for homeowners to deduct the interest paid on

their mortgage from their taxable income, reducing the amount of income tax that they owe. This

measure is commonly known as Mortgage Interest Deduction (MID) or Mortgage Interest Tax Relief

(MITR). MITR has been a part of the Luxembourg’s tax code since 1983 and has been updated since

then. As Table 2.1 shows, the level has increased over time, and there have been two recent

increases in 2017 and 2023. Since the beginning of 2023 interest payments of 3 000 euros per

person could be deducted from taxable income by households that have occupied their house in

2018 or after, for the first 6 years of occupancy. This represents an increase of 50% of deductible

interest payments from 2022 and corresponds to a deductible amount of 12 000 euros per annum

for a family of four.

Table 2.1:

Evolution of maximum mortgage interest deductible from taxable income

Source:

For the legal basis, please follow the link: https://www.legilux.public.lu/eli/etat/leg/rgd/1968/07/12/n2/jo

The objective of governments when they introduce the MITR is to subsidise home ownership,

usually for specific groups, by reducing the burden of interest payments on the mortgage. If supply

of housing is elastic, it could be expected to increase in response to the increased demand.

However, in the case of inelastic, or weakly elastic supply, mortgage interest relief acts only or

primarily to increase demand and drives up property prices. It then acts as a transfer to home

sellers, who are able to secure higher prices for the homes they sell. This is particularly the case for

untargeted measures, which are available to all borrowers, rather than a subset.

In addition, MITR primarily benefits high-income earners who can afford to purchase expensive

homes. This means that lower-income and middle-class families who may struggle to afford a

home do not benefit as much from this deduction (Andrews, Dan and Aida Caldera Sánchez

(2011)). The evolution of the share of owners with a mortgage (see Graph 2.4 a) in Luxembourg is

quite stable and also evidence that high-income families are more likely to have access to

mortgages. MITR in the case of Luxembourg is translated in a significant lower effective interest

rate (see Graph 2.5 a), in the case of high-income households, which raises households borrowing

constraints, driving up prices significantly. Finally, it can lead to a significant loss of revenue for the

government, as it reduces the amount of income tax that is collected (see Graph 2.4 b and 2.5 b).

13

kom (2023) 0600 - Ingen titel

2.

Assessment of macroeconomic vulnerabilities

Graph 2.4:

Share of owners and foregone tax revenue

a)Evolution of the share of owners with a mortgage

by income situation in relation to the risk of poverty

threshold

45

1.4%

1.2%

1.0%

b) Foregone tax revenue due to tax relief for

access to home ownership

30

0.8%

0.6%

15

0.4%

0.2%

0.0%

0

07 08 09 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21

Households with less than 60% of median equivalized income

Households with more than 60% of median equivalized income

Other

One-off tax relief for first-home buyers

Tax relief for mortgage payments

graph b: OECD Affordable Housing Database, available in https://www.oecd.org/els/family/PH2-2-Tax-relief-for-home-

ownership.pdf (please check also for notes).

Source:

European Commission services

Graph 2.5:

Nominal interest rate

7

6

5

4

3

2

1

0

-1

0

Original

2010

1996

2015

2000

2020

2005

1996

2000

2005

2010

2015

2020

Share of interest not deducted from taxes (%)

Share of interest deducted from taxes (%)

25

50

a) Nominal interest rate supported after

considering mortgage interest tax reduction, for

selected years of first occupancy compared with

the original interest rate

100

b) Share of cumulated interest for selected years

of first occupancy

75

The value of the mortgage is the estimated as 100% LTV required to acquire a 100m2 dwelling, by back casting the

2022 price per square meter in 2022 (EUR 8901, source STATEC), max marginal income tax rate of 46.62%, 30 years

loan, family size equal to 4 persons. It is assumed that the occupancy in the first year of occupancy starts in beginning of

July, meaning that there are only 6 monthly payments.

Source:

ECB and European Commission services

For a significant share of potential house buyers their demand is determined by their access to

credit or borrowing capacity. The borrowing capacity of a household is the loan that a household

can repay using a share of their monthly income. It increases with income and decreases when the

interest rate rises. An increase in MITR its equivalent to a decrease in interest rates and therefore it

increases the borrowing capacity. Table 2.2 presents an illustrative scenario about how the change

in MITR implemented in 2023 affect the amount households can borrow to by property. It shows

that the increase in the MITR is equivalent to an increase in the borrowing capacity of 4.4% (see

Table 2.2). Conversely, a complete elimination of the MITR would translate into a decrease of the

amount that can be borrowed by 11.6%. These scenarios present an illustration of the possible

range of impacts that changes to the MITR can have on house prices.

14

kom (2023) 0600 - Ingen titel

2.

Assessment of macroeconomic vulnerabilities

Table 2.2:

Impact of different MITR policies in households borrowing capacity

MITR policy scenario

Interest

Supported

compensated by tax

interest

reduction

(euros)

(euros)

31324.7

27595.1

25730.3

Change in

Change in

Borrowing capacity with

borrowing

borrowing

constant income

capacity vs MITR capacity vs MITR

in 2022

in 2023

(euros)

(euros)

(2022 MITR policy = 100) (%)

(%)

0

16937.2

48262

92

-7.7

-11.6

3729.6

16937.2

44532.4

100

0

-4.2

5594.4

16937.2

42667.6

104

4.4

0

Loan

amortization

Sum of monthly

payments

MITR = 0

MITR = 2000 per person

MITR = 3000 per person

(1) The value of the mortgage is the estimated as 100% LTV required to acquire a 100m2 dwelling, considering the 2022

price per square meter in 2022 (EUR 8901, source STATEC), max marginal income tax rate of 46.62%, 30 years loan,

family size equal to 4 persons and the average mortgage interest rate in January 2023 (source ECB)..

Source:

European Commission services

References:

Andrews, Dan and Aida Caldera Sánchez (2011),

“The Evolution of Homeownership Rates in

Selected OECD Countries: Demographic and Public Policy Influences”,

OECD Journal: Economic

Studies, Vol. 2011/1.

OECD (2021),

Brick by Brick: Building Better Housing Policies,

OECD Publishing, Paris.

OECD (2022),

Affordable Housing Database.

OECD (2022),

Housing Taxation in OECD Countries,

OECD Tax Policy Studies, No. 29, OECD

Publishing, Paris,

Overall, a number of structural challenges remain to address the mentioned

vulnerabilities.

The fiscal treatment of housing tenure stimulates homeowner occupancy

especially via mortgage interest deductibility and other fiscal instruments supporting

homeownership. The recent planned reforms of the recurrent taxation of immovable property

based on up-to-date real estate valuations and measures increasing the opportunity costs of

unused land in urbanised areas and unoccupied dwellings are focused on supply-side restrictions.

These measures combine with ongoing reforms of spatial planning to accelerate a more efficient

land-use across the national territory, including measures involving municipalities in selectively

increasing residential density in areas well-connected to the transport network. Furthermore,

measures aiming to align housing supply and demand are more effective when integrated in

policies including local, regional, and national level. This strategy should ensure consistency with

complementary critical policy areas, such as transport and education, and their contribution to

social impact and environmental sustainability. Housing affordability has been deteriorating in

particular for low-income households that do not profit from subsidised social or affordable

housing. The increase in supply of social rental housing can reduce the affordability issue,

especially if access to it is made conditional on recurrent means testing ensuring better targeting to

those most in need. The functioning of the private rental sector can benefit from relaxing the rules

on renting parts of housing units and from conversion of existing dwellings into rental housing.

15

kom (2023) 0600 - Ingen titel

2.

Assessment of macroeconomic vulnerabilities

Conclusion

Luxembourg faces vulnerabilities relating to high house prices and high household

indebtedness.

Strong population growth pushed up the demand for housing in Luxembourg. The

supply of housing has not kept up with demand, restricted by the limited use of land available for

construction and the practice of land hoarding. The increasing gap between housing demand and

supply resulted in strong house price increases and deteriorating affordability of housing. Increases

in the price-to-income ratio mainly reflect high valuations of residential real estate, which rose

faster than incomes, leading to increasing financial risks related to household indebtedness. This

long-term price dynamics have led to an overvaluation in the housing market according to the

standard metrics. Affordability concerns have increased in the Luxembourg housing market, as

household debt in terms of disposable income continued trending upward and remains

substantially higher, compared to other Member States. Despite high household debt, the supply

shortage in Luxembourg’s housing market helped cushioning the turn of the financial cycle. Strong

fiscal position allowed the government to introduce measures to support households and firms and

stabilise the economy. Households’ financial assets are also high and because indebtedness

increases towards the higher levels of income and wealth, this mitigates the risks.

Significant policy measures have been adopted, which will contribute to addressing

vulnerabilities relating to housing debt and house prices in the medium term, but

structural challenges remain.

National authorities activated both capital and borrower-based

macroprudential measures with effect from 1 January 2021 to reduce mortgage credit related

financial risks. The measures adopted to increase the supply of housing, include tax reforms for

unused land and empty dwellings, the promotion of affordable and social housing, and the reform

of the rental market, which constitute a significant progress in addressing the housing market

issues. However, considering the current slowdown a step-up in efforts and prioritise their

implementation can stimulate housing supply more swiftly. The supply side fiscal measures can be

more effective in combination with the ongoing reform of land-use planning. Moreover, a reduction

or elimination over time of the mortgage interest rate tax deductibility, that was recently increased,

would reverse the current situation where fiscal policy subsidises indebtedness, increases

borrowing and stimulates demand and provide a windfall gain to home sellers. The structural

imbalance between housing demand and supply is expected to continue to drive up house prices in

the medium term. An increase in the supply of social rental housing and better targeted to the

most in need can alleviate the affordability issue. Lastly, a better collection of data in the real

estate market can improve the design of policies and to monitor their implementation.

Based on the findings in this in-depth review, the Communication “European Semester –

2023 Spring Package” sets out the Commission’s assessment as to the existence of

imbalances or excessive imbalances in Luxembourg, in line with Regulation 1176/2011.

(

35

)

(

35

) European Commission (2023), European Semester Spring Package 2022, COM(2023) 600 final.

16

kom (2023) 0600 - Ingen titel

2.

Assessment of macroeconomic vulnerabilities

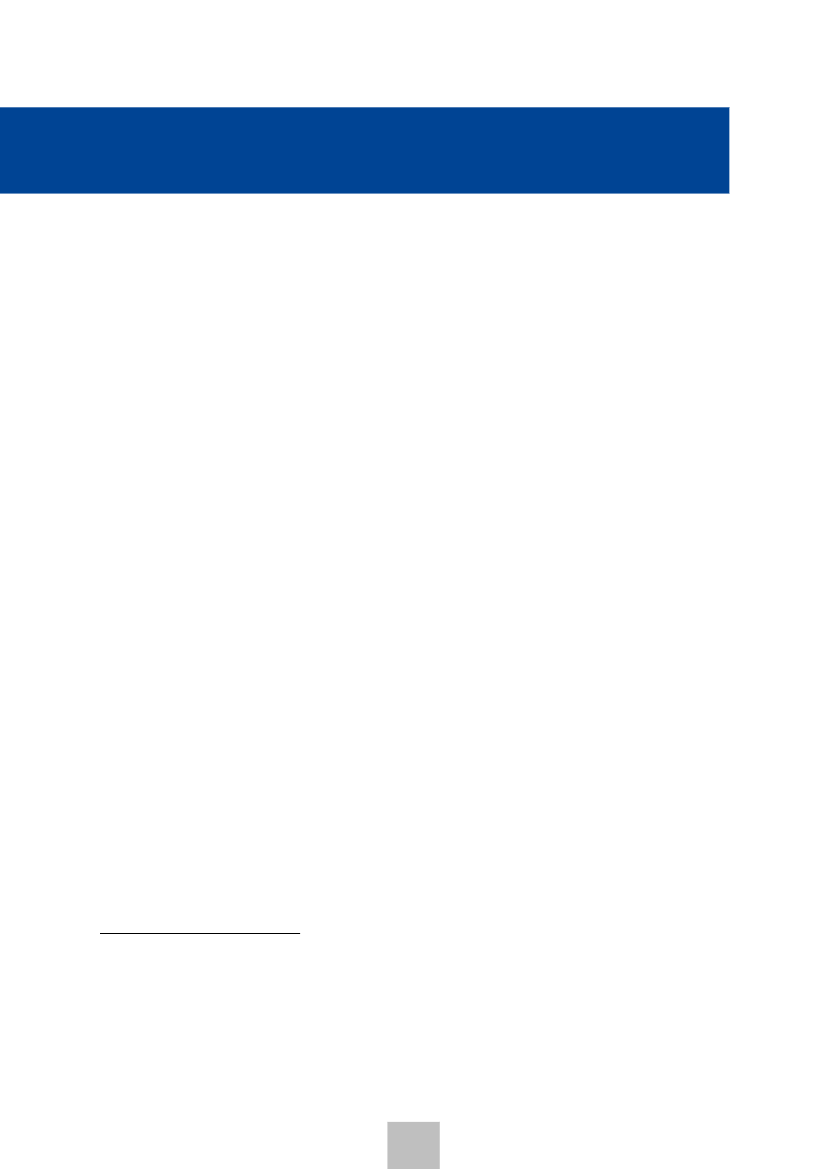

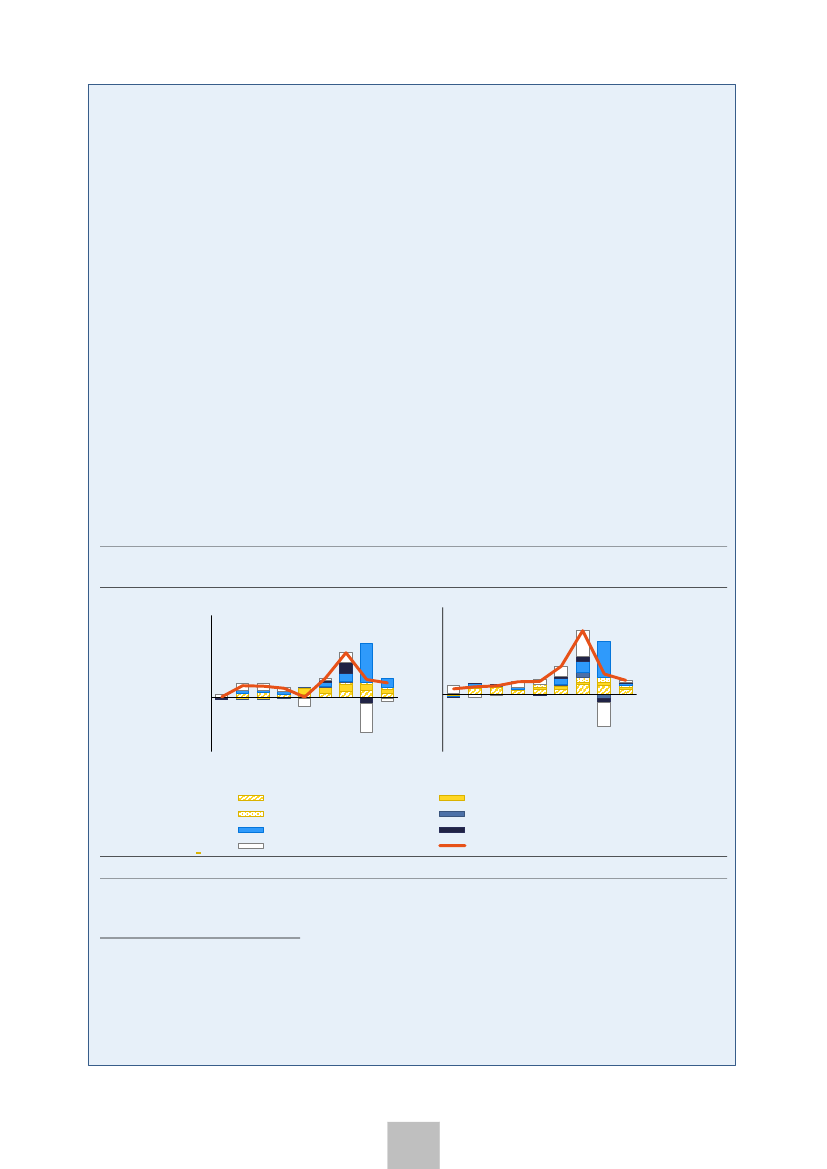

Graph 2.6:

Selected graphs, Luxembourg

a) New loans to households for house purchase

1200

1000

millions EUR

4,000

50,000

3,000

b) Number of completed dwellings

40,000

800

30,000

600

20,000

400

200

0

19-01

20-01

21-01

22-01

23-01

2,000

1,000

10,000

0

0

Two and more dwelling residental buildings

One-dwelling residental buildings

Renegotiation

Total

140

Pure new loans

Outstanding amount (rhs)

100

d) Overvaluation metrics

Model-based valuations gap

Price to income vs. hist. avg.

Price to rent vs. hist. avg.

Overall valuation gap

c) Housing transactions

% deviation of current price

17Q4

18Q4

19Q4

20Q4

21Q4

22Q4

120

index (2021Q4 =100)

50

100

80

0

60

-50

02

04

06

08

10

12

14

16

18

20

22

Value of housing transactions

Number of housing transactions

Transaction price

1600000

12000

175

f) Advertised rent prices

e) Regional house prices

1200000

9000

150

800000

6000

125

400000

3000

100

0

C.Esch

C.Lux

Total

Nord

CM

Est

0

T1 T3 T1 T3 T1 T3 T1 T3 T1 T3 T1 T3 T1 T3 T1 T3 T1 T3 T1 T3 T1 T3 T1 T3 T1 T3

2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 2019 2020 2021 2022

House

Apartment

Houses (EUR)

Appartments (EUR/m2, rhs)

graph e Publicité Foncière, STATEC calculations - Habitat Observatory, transactions from January 1, 2022 to December

31, 2022; Note: C.Lux stands for the canton de Luxembourg, CM stands for the combined area of the cantons of Capellen

and Mersch, C.Esch stands for the canton d'Esch-sur-Alzette. The east zone corresponds to the cantons of Echternach,

Grevenmacher and Remich. Finally, the northern zone includes the cantons of Clervaux, Diekirch, Redange, Vianden and

Wiltz

Source:

Statec, Eurostat and European Commission services

17

kom (2023) 0600 - Ingen titel

2.

Assessment of macroeconomic vulnerabilities

Box 2: Inflation exposures and cross-border pass-through

This box sheds light on the sources of inflation in Luxembourg and its spill-overs with EU

partners.

The period since 2021 has been characterized by pandemic aftershocks and global

supply chain disruptions compounding global inflationary pressures and a surge in commodity

prices triggered by Russia’s war of aggression against Ukraine. As a result, inflation in Luxembourg

surged to unprecedented levels. In response, wages and profits also picked up across the EU, which

further added to price pressures in Luxembourg. With input-output data, domestic inflation can be

decomposed into the contributions from key cost factors. Taking into account some data

limitations, the framework can be used to attribute consumer and investment price changes to i)

extra-EU import price changes, which include both directly imported inflation and inflation passed

through from EU partners import costs ii) domestic unit labour cost changes iii) domestic unit profit

changes, including indirect taxation changes and iv) rest-of-EU value added price changes. (

36

)

Data suggests that much of inflation in Luxembourg in 2022 reflected surging import

prices, which are projected to continue driving inflation over the forecast horizon.

In

2022, as shown in Graph 2.7, extra-EU price changes and costs passed through EU partners were a

key driver of consumption and investment inflation. Energy inflation contributed only mildly. Spill-

overs from value added inflation in other EU countries also remained limited. The contribution from

domestic value-added inflation, which covers wages and profits, was significant in 2022 and is

expected to remain sizeable in 2023 and 2024. This reflects increases in both, unit profits and unit

labour cost, with a slightly stronger impact from the latter. Still, consumer and investment inflation

is expected to be sustained mainly by non-energy imports from outside the EU. Value added

inflation in EU partners is also set to contribute somewhat, particularly to investment inflation.

Graph 2.7:

Components of gross fixed capital formation deflator growth and consumer price

inflation

15

LU: contribution to domestic CPI

deflator growth

15

LU: contribution to domestic GFCF

deflator growth

% change (year-on-year)

10

5

0

-5

-10

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

% change (year-on-year)

10

5

0

-5

-10

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

Domestic ULC

RoEU value added deflator

Other imports from Extra-EU

Residual

Unit profits (&taxes)

Energy imports from Extra-EU

RoEU import cost passthr.

Deflator growth YoY

Source:

European Commission services

(

36

) The graphs below are based on national accounts data and the Commission’s Spring 2023 forecast, which are combined

through a ‘Ghosh’ matrix based on Eurostat’s Figaro input-output available for 2015-2020. HICP is taken as the measure of

the price of private consumption, including non-residents. Energy import prices from extra-EU reflect realised median prices

until 2022, and energy price assumptions underlying the Spring forecast thereafter. Other goods prices reflect median

Eureopan prices per industry until 2022, and forecast non-energy goods and service trade prices for 2023-2024. Value

added deflators are assumed to affect all industries within a country to the same degree. For a similar analysis using an

input-output-based methodology, see “Inflation Differentials in Europe and Implications for Competitiveness: Thematic

Note to Support In-Depth Reviews” European Commission 2023, Institutional paper 198.

18

kom (2023) 0600 - Ingen titel

2.

Assessment of macroeconomic vulnerabilities

Table 2.3:

Selected economic and financial indicators (Part 1), Luxembourg

all variables y-o-y % change, unless otherwise stated

Real GDP

Potential growth (1)

Co ntrib utio n to GDP gro wth:

Domestic demand

Inventories

Net exports

Co ntrib utio n to po tential GDP gro wth (1):

Total Labour (hours)

Capital accumulation

Total factor productivity

Output gap (2)

Unemployment rate

Harmonised index of consumer prices (HICP)

GDP deflator

External position

Current account balance (% of GDP), balance of payments

Trade balance (% of GDP), balance of payments

Primary income balance (% of GDP)

Secondary income balance (% of GDP)

Current account explained by fundamentals (CA norm, % of GDP) (3)

Required current account to stabilise NIIP above -35% of GDP over 20Y (% of GDP) (4)

Capital account balance (% of GDP)

Net international investment position (% of GDP)

NENDI - NIIP excluding non-defaultable instruments (% of GDP) (5)

Net FDI flows (% of GDP)

Com petitiveness

Unit labour costs (ULC, whole economy)

Nominal compensation per employee

Labour productivity (real, hours worked)

Real effective exchange rate (ULC)

Real effective exchange rate (HICP)

Export performance vs. advanced countries (% change over 5 years)

Private sector debt

Private sector debt, consolidated (% of GDP)

Household debt, consolidated (% of GDP)

Household debt, fundamental benchmark (% of GDP) (6)

Household debt, prudential threshold (% of GDP) (6)

Non-financial corporate debt, consolidated (% of GDP)

Corporate debt, fundamental benchmark (% of GDP) (6)

Corporate debt, prudential threshold (% of GDP) (6)

Private credit flow, consolidated (% of GDP)

Corporations, net lending (+) or net borrowing (-) (% of GDP)

Households, net lending (+) or net borrowing (-) (% of GDP)

Net savings rate of households (% of net disposable income)

2003-07

4.7

3.9

1.8

0.3

2.5

1.9

1.3

0.7

1.1

4.4

3.0

3.7

6.9

28.7

-22.0

0.2

3.7

2.7

0.3

22.7

.

.

1.9

3.5

1.7

0.6

1.6

25.8

217.9

45.5

53.6

155.6

172.4

62.6

175.0

46.1

6.2

-0.1

5.5

2008-12

0.6

2.2

1.9

-0.1

-1.3

1.3

1.3

-0.3

-1.5

4.9

2.7

3.8

5.7

36.5

-30.6

-0.2

4.3

1.4

-0.4

12.1

.

.

4.3

2.2

-1.1

2.1

0.4

16.5

287.4

55.1

61.6

153.2

232.3

72.1

170.9

5.1

0.5

0.2

6.1

2013-18

2.6

2.2

1.4

0.2

1.0

1.6

1.0

-0.5

-0.8

6.0

1.1

2.7

4.7

40.6

-36.4

0.5

4.7

4.4

0.0

64.9

-3442.3

47.8

3.2

2.3

-0.1

1.5

0.6

17.8

298.9

60.5

69.2

169.3

238.4

79.0

183.6

13.3

-0.1

0.5

7.9

2019

2.3

2.2

2.7

0.1

-0.4

1.7

0.8

-0.3

-0.5

5.6

1.6

1.4

3.4

32.6

-29.5

0.3

5.1

4.8

-0.1

67.8

-4153.8

107.6

3.1

1.9

-0.8

1.0

-0.4

5.2

310.8

67.2

69.9

113.1

243.6

79.1

137.2

24.9

-5.8

1.1

8.3

2020

-0.8

1.9

-1.7

-0.3

1.2

1.4

0.7

-0.2

-3.2

6.8

0.0

4.7

3.2

32.7

-29.3

-0.3

5.2

4.6

-0.1

63.9

-4148.8

-32.2

3.8

1.2

3.4

-0.4

0.1

18.4

320.3

68.5

77.5

115.6

251.7

86.6

143.5

42.9

-0.4

6.1

19.1

2021

5.1

1.9

5.0

0.4

-0.3

1.4

0.8

-0.3

-0.1

5.3

3.5

6.2

4.6

34.7

-31.0

0.9

5.2

2.9

1.2

40.4

-4638.1

173.6

3.9

6.0

-2.0

3.5

0.8

19.0

340.6

66.0

77.0

100.6

274.6

85.0

126.5

53.9

0.7

2.8

12.4

2022

1.5

2.2

1.4

-0.1

0.2

1.9

0.7

-0.5

-0.8

4.6

8.2

6.4

5.0

28.4

-24.2

0.8

5.3

2.2

0.5

28.2

-3767.0

47.6

7.4

5.4

-2.3

3.6

-1.1

.

337.1

66.3

79.3

99.4

270.8

86.3

123.2

21.3e

1.8

2.8

.

forecast

2023

1.6

2.3

0.9

0.0

0.7

2.2

0.6

-0.5

-1.5

4.8

3.2

5.5

6.1

.

.

.

5.2

2.3

.

.

.

.

7.8

6.9

-1.8

1.9

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

4.6

3.8

.

2024

2.4

2.3

1.5

0.0

0.9

2.1

0.6

-0.4

-1.4

5.0

2.6

3.4

5.9

.

.

.

5.1

2.5

.

.

.

.

3.3

3.4

-0.9

-0.2

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

5.6

2.7

.

(e) estimate based on ECB quarterly data

(1) Potential output is the highest level of production that an economy can reach without generating inflationary

pressures. The methodology to compute the potential output is based on K. Havik, K. Mc Morrow, F. Orlandi, C. Planas, R.

Raciborski, W. Roeger, A. Rossi, A. Thum-Thysen, V. Vandermeulen, The Production Function Methodology for Calculating

Potential Growth Rates & Output Gaps, COM, European Economy, Economic Papers 535, November 2014.

(2) Deviation of actual output from potential output as % of potential GDP.

(3) Current accounts in line with fundamentals ("current account norms") are derived from reduced-form regressions

capturing the main determinants of the saving-investment balance, including fundamental determinants, policy factors

and global financial conditions. See L. Coutinho et al. (2018), "Methodologies for the assessment of current account

benchmarks", European Economy, Discussion Paper 86/2018, for details.

(4) This benchmark is defined as the average current account required to halve the gap between the NIIP and the

indicative MIP benchmark of -35% of GDP over the next ten years, or to stabilise the NIIP at the current level if it is

already above the indicative MIP benchmark. Calculations make use of Commission’s T+10 projections.

(5) NENDI is a subset of the NIIP that abstracts from its pure equity-related components, i.e. foreign direct investment

(FDI) equity and equity shares, and from intracompany cross-border FDI debt, and represents the NIIP excluding

instruments that cannot be subject to default.

(6) Fundamentals-based benchmarks are derived from regressions capturing the main determinants of credit growth and

taking into account a given initial stock of debt. Prudential thresholds represent the debt threshold beyond which the

probability of a banking crisis is relatively high, minimising the probability of missed crisis and that of false alerts.

Methodology to compute the fundamentals-based and the prudential benchmarks based on Bricongne, J. C., Coutinho, L.,

Turrini, A., Zeugner, S. (2019), “Is Private Debt Excessive?”, Open Economies Review, 1- 42.

Source:

Eurostat and ECB as of 2023-04-28, where available; European Commission for forecast figures (Spring forecast

2023)

19

kom (2023) 0600 - Ingen titel

2.

Assessment of macroeconomic vulnerabilities

Table 2.4:

Selected economic and financial indicators (Part 2), Luxembourg

all variables y-o-y % change, unless otherwise stated

Housing m arket

House price index, nominal

House price index, deflated

Overvaluation gap (%) (7)

Price-to-income overvaluation gap (%) (8)

Residential investment (% of GDP)

Governm ent debt

General government balance (% of GDP)

General government gross debt (% of GDP)

Banking sector

Return on equity (%)

Common Equity Tier 1 ratio

Gross non-performing debt (% of total debt instruments and total loans and advances) (9)

Gross non-performing loans (% of gross loans) (9)

Cost of borrowing for corporations (%)

Cost of borrowing for households for house purchase (%)

2003-07

10.9

8.2

-7.5

-10.4

3.1

1.0

7.9

.

.

.

.

4.0

3.9

2008-12

3.1

1.2

1.9

1.5

3.2

0.8

17.7

-1.1

15.9

0.2

.

2.8

2.6

2013-18

5.6

4.2

11.1

17.7

3.7

1.6

21.3

5.7

26.4

0.8

1.0

1.5

1.8

2019

10.1

8.3

26.9

37.5

4.0

2.2

22.4

4.4

21.1

0.5

0.6

1.4

1.4

2020

14.5

13.1

40.3

50.2

3.8

-3.4

24.5

3.0

22.0

0.6

0.7

1.3

1.3

2021

13.9

12.4

56.0

69.3

3.3

0.7

24.5

3.8

22.4

0.5

0.6

1.3

1.4

2022

9.6

3.8

62.6

80.7

3.2

0.2

24.6

.

.

.

0.7

3.1

3.1

forecast

2023

.

.

.

.

.

-1.7

25.9

.

.

.

.

.

.

2024

.

.

.

.

.

-1.5

27.0

.

.

.

.

.

.

(7) Unweighted average of price-to-income, price-to-rent and model valuation gaps. The model valuation gap is

estimated in a cointegration framework using a system of five fundamental variables; total population, real housing

stock, real disposable income per capita, real long-term interest rate and price deflator of final consumption expenditure,

based on Philiponnet, N., Turrini, A. (2017), "Assessing House Price Developments in the EU," European Economy -

Discussion Papers 2015 - 048, Directorate General Economic and Financial Affairs (DG ECFIN), European Commission.

Price-to-income and price-to-rent gaps are measured as the deviation to the long term average (from 1995 to the latest

available year).

(8) Price-to-income overvaluation gap measured as the deviation to the long term average (from 1995 to the latest

available year).

(9) Domestic banking groups and stand-alone banks, EU and non-EU foreign-controlled subsidiaries and EU and non-EU

foreign-controlled branches.

Source:

Eurostat and ECB as of 2023-04-28, where available; European Commission for forecast figures (Spring forecast

2023)

20